|

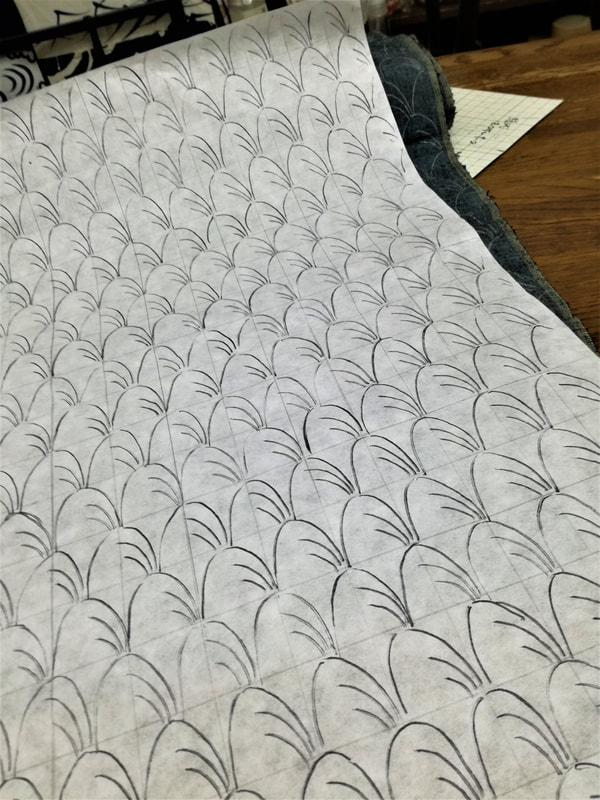

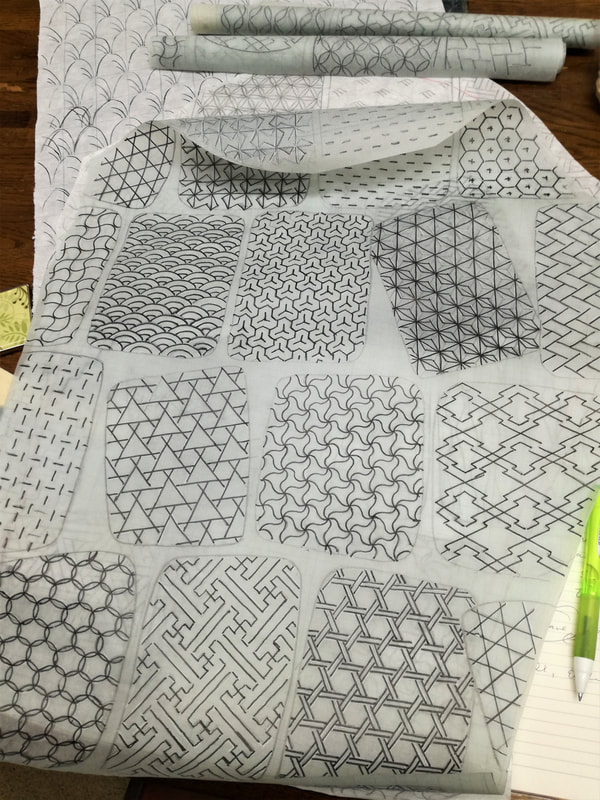

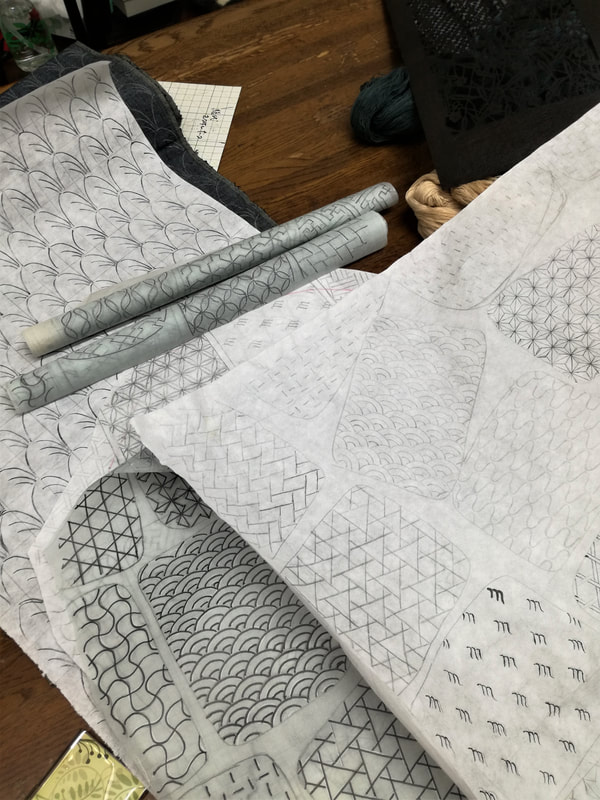

Following a tip I’d received about a sashiko shop, I recently went insearch of it in the backstreets of Ueno one rainy afternoon. As I stood outside staring through the window, a straight-backed elderly lady came to the door. “May I come in and look,” I asked. “Well I’m usually closed on Monday but please do,” she graciously replied. It was only when I stepped through the door that I realised this wasn’t a shop at all, it was a workshop. Every available surface surrounding the table in the centre was covered with baskets, drawers and boxes from which scraps of cloth of every size and colour spilled out. “I love fabric,” said Hisaoka-san, for that was her name. In the course of our conversation it became clear she wasn’t just saying this. She meant it from the heart and it shaped the way she lived. With no introductions, explanation, and barely any prompting on my part, she somehow understood I was there to hear about sashiko and immediately launched into telling me all about her ideas and methods. She pointed out a beautiful noren (curtain), made from blue and white panels of fabric taken from discarded shop samples of yukata (cotton summer kimono), and likened what she did with cloth to Spanish architect Antoni Gaudi’s use of broken plates. An irregular shaped sashiko-stitched mat under my teacup had been made from leftover scraps of a suit she had made. Hisaoka-sensei was born and raised in Tokyo. She never learned to sew, sashiko was just something that she had always done since she was a child, to save and reuse cloth. She used the phrase onkochishin many times to describe her philosophy. It means looking to the past and using old things to make something new or inform the future. People like old things, she told me, because they can get a sense of time from them, and time is something you cannot buy. The shop where she holds her sashiko classes is old. Fifteen years ago when her previous premise was knocked down to build condominiums she searched hard for another old building to house the classes she has been teaching for thirty years. In her youth, however, she had done another kind of work, I’m not sure what exactly, but it was related to making designs. That explains to a certain degree perhaps, her unique method of making sashiko designs. She showed me a bolt of cloth she was in the process of hand printing with an elongated nowaki (autumn grass) pattern for her students to stitch. She uses shoji (paper screen door) paper to first draw the design on before transferring it to the cloth. The hand drawn nowaki were evenly spaced overall in the grid, but all slightly different and the overall effect was totally charming. She also hand dyes the thread, as part of her credo of doing everything herself from start to finish. I was astonished when she took me to a corner of the room and started pulling out reams and reams of designs stuffed into a cardboard box. I’ve never seen shoji paper used in this way before but have to say how impressed I am with its strength, flexibility, and durability. I had also never imagined that shoji paper could be used for dressmaking, but Hisaoka-sensei showed me the sheets on which she had drawn the sashiko patterns for a suit she had been commissioned to design and stitch. Apparently it is now being sewn up at a department store. Like most sashiko teachers I’ve met, Hisaoka-sensei said that there are no rules in sashiko. What that means in my experience, however, is there are rules, related to the basic technique of how you hold the needle and method of stitching, and it’s only once you have control over that aspect that you are free. In Hisaoka-sensei’s case, it’s the order of stitching she is particular about. “You need to stitch the pattern in the right order,” she told me. Asanoha (hemp leaf) is one to be particularly careful about. She herself had learned what that right order was from experience. By stitching and unpicking, stitching and unpicking over and over again, she had discovered it. You cannot succeed unless you fail, she said. What this all tells me is that there is an aesthetic that defines sashiko. No matter how easy, free-handed or versatile it is, it is not simply decorative running stitch, and there is a discernable essence that marks a piece of stitching as authentically sashiko. I call it perfect imperfection. Another nugget of wisdom she imparted is that many people can talk about a particular skill, but few can really do it well. To be able to do something well you need to practice it for ten years. By that standard I still have another five years to go with sashiko!

This was a very special encounter. I had arrived unannounced, yet been greeted with gracious hospitality and gifted the gleanings of wisdom earned over a lifetime of experience. We parted with a promise that I would visit again one day—this time with prior notice—to view the store of finished sashiko pieces in the upstairs room. I can’t wait!

2 Comments

|

Watts SashikoI love sashiko. I love its simplicity and complexity, I love looking at it, doing it, reading about it, and talking about it. Archives

September 2022

Categories

All

Sign up for the newsletter:

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed