|

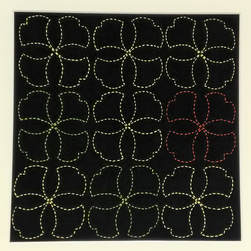

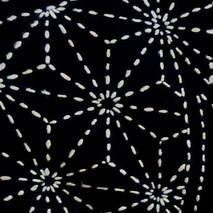

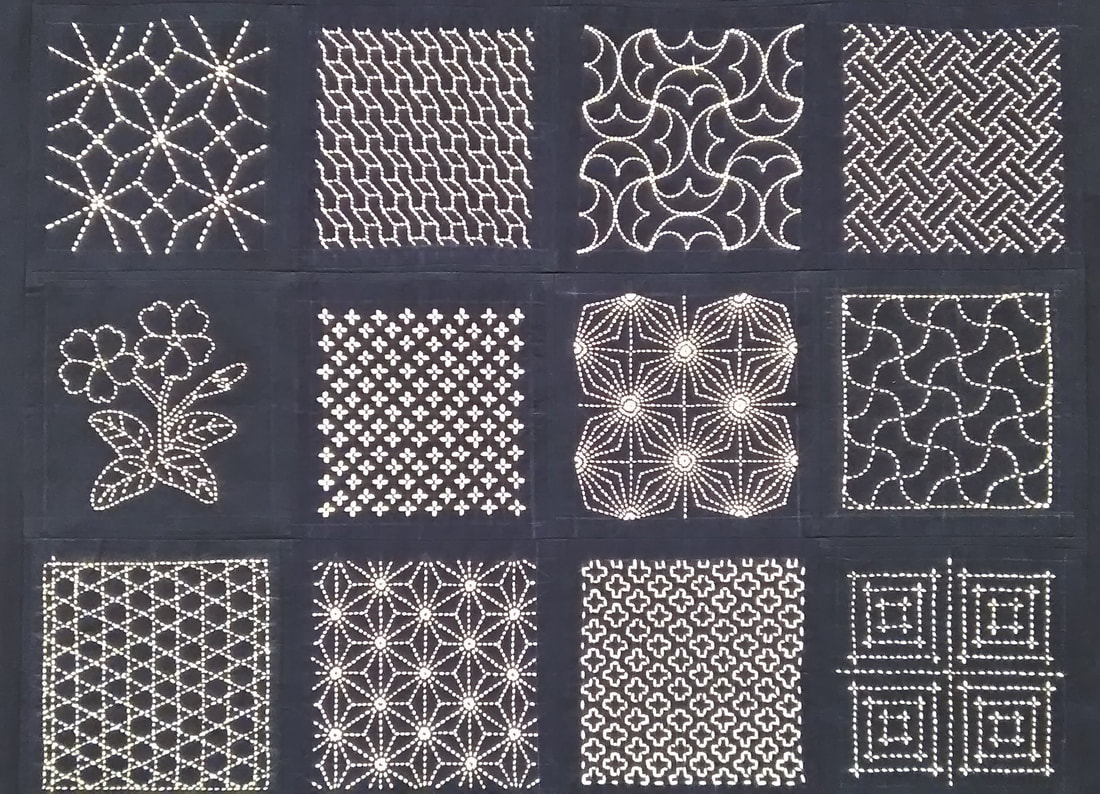

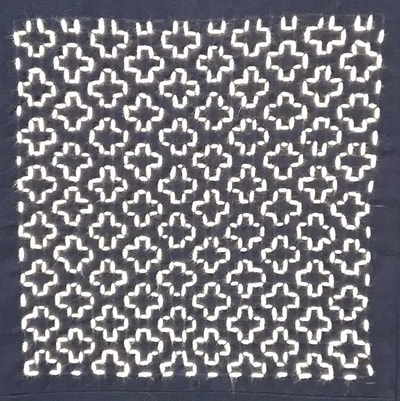

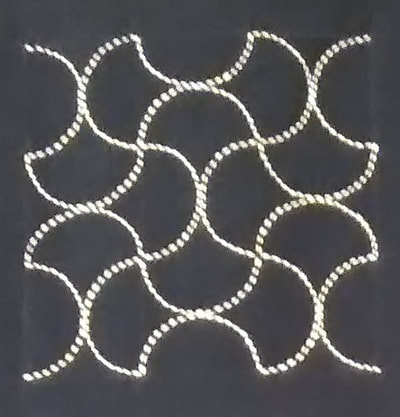

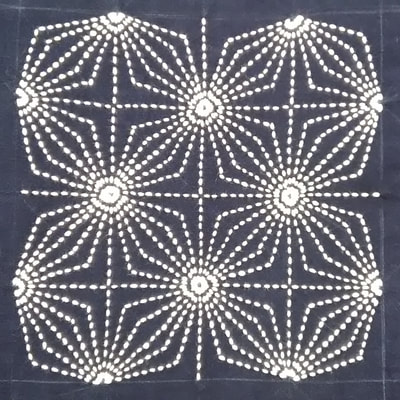

Last week my sashiko group participated in an annual exhibition held in the local Station Gallery. A train station might seem an unlikely location for a gallery, but actually it makes sense, as it’s the most central place in town and gets a lot of potential viewers passing by. Which happily was the case this time.  Icho tsunagi pattern (linked ginko leaves) Icho tsunagi pattern (linked ginko leaves) For the exhibition I decided to make another framed piece of sashiko to add to a series I started last year. This year I chose to stitch the pattern icho tsunagi, which means linked ginko leaves. As time was running short, I cheated by blowing up the pattern on a photocopier instead of enlarging the proportions on graph paper (shhh…don’t tell Sensei!). Then I cut and taped the paper pieces together to fit the cloth dimensions, taped chaco paper (transfer paper for tracing designs onto fabric) to the back of this pattern and traced over the design with a ballpoint pen to imprint it on the fabric. The autumn ginko leaves are gorgeous at this time of year and I wanted to reflect that by using thread in autumn colours of green and yellow, but unfortunately the result wasn’t as vivid as I hoped, so I ended up putting in one orange leaf for some contrast variation. Anyway, I was pleased with the result, and best of all Sensei praised my corner stitches. Phew! I didn’t want to let the side down… My fellow sashikoists all contributed their work from the past year and it was so exciting to see the inventive and wonderful pieces they’ve done all gathered in the one place. A real Aladdin”s cave! I had intended to describe these for you here, but realized I couldn’t possibly do them justice, so I’ll keep that for some later posts. The most thrilling exhibits, however, were the two wall hangings that were on display for the first time. Take a look at the amazing work below! These were the result of a joint project we’ve been working on all year, stitching squares fifteen by fifteen centimetres in length with whatever patterns we liked. When the time was up we gathered up all the squares and put them together to see what size hanging was possible. It turned out we had enough for two. Sensei gave no stipulations whatsoever as to what patterns we should stitch, but the overall balance seemed to be just right, and a lovely sampler of all the different styles of stitches; the densely stitched hitomezashi (single stitch), kyokusen moyozashi (curved line patterns), chokusen moyozashi (straight line patterns) and jiyuzashi (free stitching). I could look at these all day in wonder and never tire. What a gorgeous illustration of the beauty of sashiko!

1 Comment

When I started doing sashiko it wasn’t long before I learned the word fukin. All the books and kits seemed to feature fukin, which was obviously a square cloth approximately thirty something centimetres in size, stitched with a variety of patterns. For a long time I was so absorbed in grappling with the stitching and patterns it didn’t occur to me to wonder exactly what fukin were. But then it struck me: What the heck are they? I didn’t see them available ready-made in shops, or having any specific function in contemporary Japanese daily life. Now I can tell you what I’ve learned about fukin since then. Although there are regional variations in patterns and function, fukin had many uses in the days before towels became widespread, both practical and decorative. For example, they were used as placemats for the individual tray tables that people ate from in the days before sitting around a table to eat became the custom from around the 1920s onwards. They were also used to cover teacups, cooking implements, or as a simple decorative mat.  Hanafukin (literally ‘flower cloth’), as the fukin stitched on bleached cotton are called, were part of women’s lives in many ways. Daughters in samurai families learned to sew them to acquire such desirable mental attributes as perseverance and patience, whereas girls in farming families, learned to make them out of necessity, and at night, when all the other chores were done, women would sit around and do the sewing together. If a woman became widowed, other people might commission her to make hanafukin as a way of discreetly giving financial support. Mothers sewed hanafukin for their daughters to take when they went as a bride to live in another family. I suspect this is how the word hanafukin originated, since the word for bride is hana yome. From the time her daughter was born, a mother would begin to make hanafukin stitched with various patterns representing good wishes for health, happiness, and different auspicious occasions and seasonal events. Stitching that was decorative in purpose was known as moyozashi (pattern sashiko), whereas stitching that was designed for practical purposes was known as jizashi (‘ground’ sashiko). Jizashi stitching, which is as resilient as it is beautiful, was used for mending clothes, reinforcing cloth to make it warmer, or making covers or pockets for tools. A new bride would use the hanafukin her mother had given her as a model for each sewing task she needed to perform. In this way hanafukin were a practical sign of a mother’s love for her daughter. A few hours after writing the above, I found myself in a tiny backstreet bar in Tokyo drinking shochu spirits in hot tea and, as often happens with me, not surprisingly, sashiko came up in the conversation. When I mentioned hanafukin, the bar owner immediately brought out two to show me that she had received from her own mother. I was thrilled to see these well-used and loved hanafukin, which made me feel like going straight home and getting started on stitching for my own daughter! I am indebted to Hiroko Kondo’s book Akita ni tsutawaru oiwai no hari shigoto: Yomeiri dogu no hanafukin (Traditional congratulatory needlework in Akita: Hanafukin, a bride’s trousseau), Kurashi no techosha, 2013 - Amazon Japan affiliate link here. It is a wonderful reference and the patterns in this book are stunning, I will introduce it in more detail at a later date.

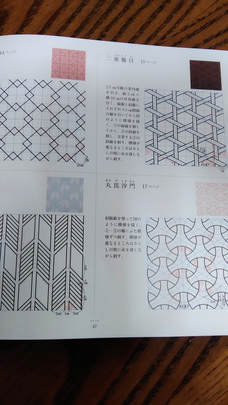

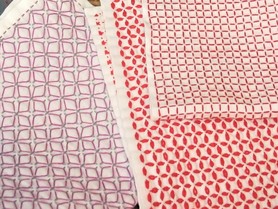

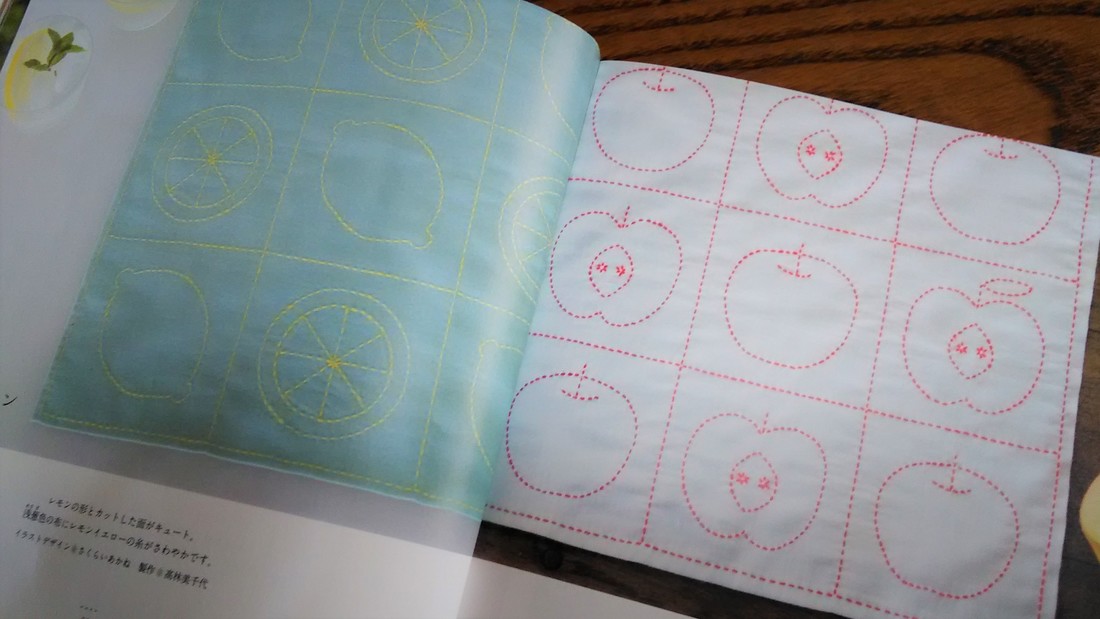

As I mentioned in my last post, my teacher, Nakazaki Sensei, studied under Eiko Yoshida (1922-2002) who played a major part in reviving traditional sashiko and creating the sashiko boom in modern Japan. Nowadays Eiko Sensei’s students and followers are led by Kumiko Yoshida. Kumiko Sensei and her students cooperated with the publication of a book released by Shufu to Seikatsu Sha in June of this year, Sashiko no fukin: dento moyo to hokuo moyo (Sashiko Fukin: Traditional Patterns and Northern European Patterns - Amazon Japan affiliate link) Nakazaki Sensei stitched three of the fukin that appear in this book.  As is obvious from the title the book features fukin stitched on cloth squares of 33cm and 34cm. Sashiko books commonly feature fukin, and I have to admit for a long time I wondered what on earth they were. That’s a topic I’d like to explore in more detail in another post soon, but for now let’s say that fukin are basically square cloths that serve decorative and practical purposes. This book shows fifteen fukin stitched with traditional sashiko patterns and fifteen stitched with Northern European motifs. What sets my heart beating when I leaf through the pages is the glorious use of colour; sky blue and lemon yellow on white, pink on olive, grey on red, yellow on green, etcetera etcetera, plus the obligatory white on blue. Though I do love the traditional blue and white, I find the use of colour in contemporary sashiko really exciting. It allows so much potential for artistic expression, and thinking about possible colour combinations of pieces is one of the most enjoyable aspects of sashiko for me. The other thing I find striking about this book is how well these Northern European motifs adapt to sashiko, whether in freestyle form, such as the cloths featuring food and vegetable designs, or as repeated patterns like the trees or butterflies. It’s another marvellous illustration of the adaptability and infinite potential of sashiko. The contents of the book include a one-page photograph of each fukin, basic instructions for sashiko, instructions for reproducing and stitching the traditional patterns, and diagrams for reproducing the Northern European motifs. Of the traditional patterns, the hanazashi (flower) particularly caught my eye with its colourful combination of orange, yellow, pink and red threads that very aptly suggest a bright patch of flowers, and makes a nice contrast with the Northern European flower motif of three different wildflowers. Once you start thinking of ordinary everyday things around you in terms of patterns and colours, there’s no end of inspiration for sashiko! |

Watts SashikoI love sashiko. I love its simplicity and complexity, I love looking at it, doing it, reading about it, and talking about it. Archives

September 2022

Categories

All

Sign up for the newsletter:

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed