|

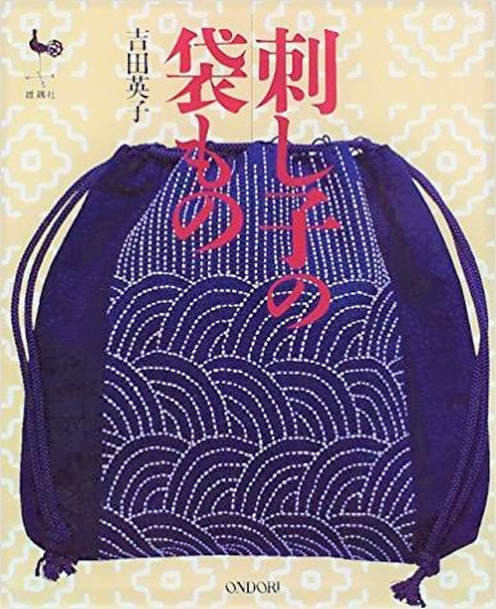

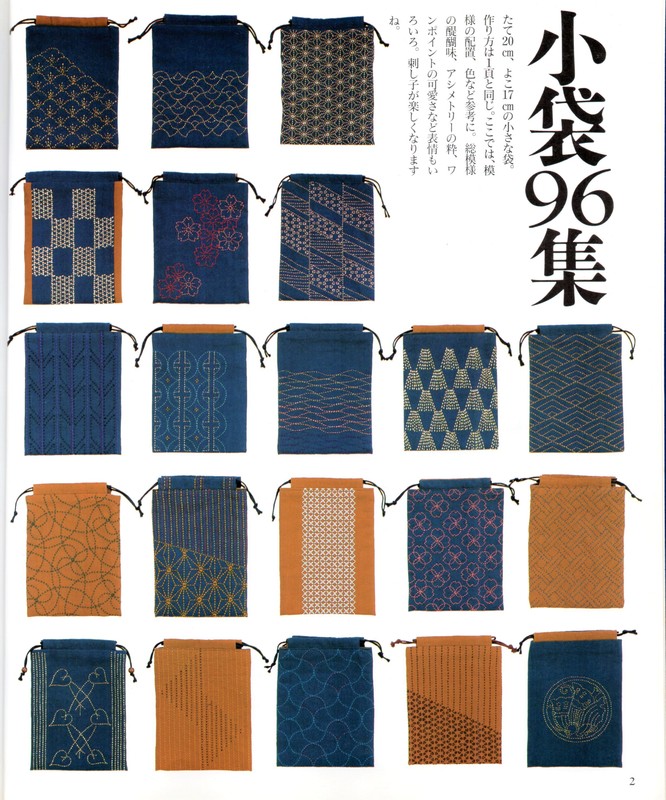

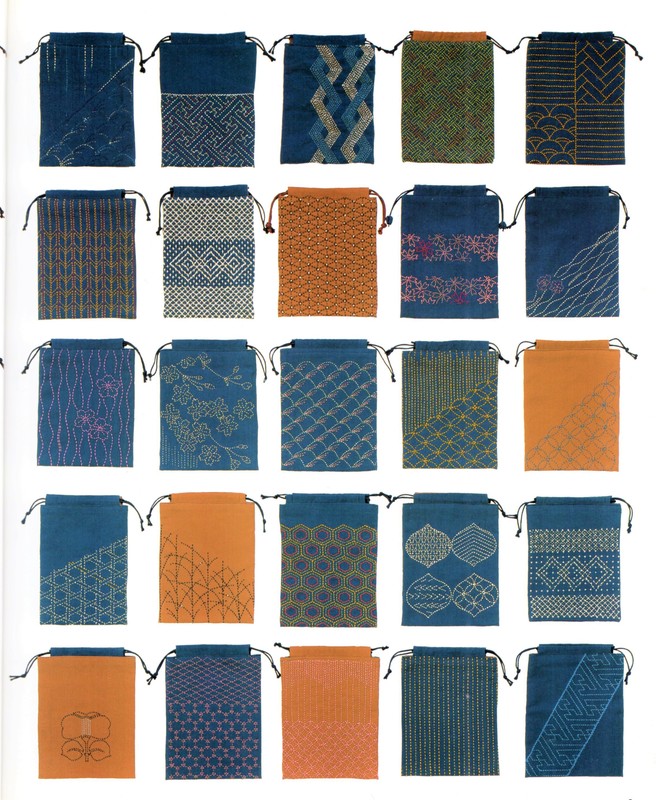

After writing in my last post about the exquisite kinchaku bag I received, I felt like revisiting a book in my collection featuring kinchaku and other bags. This book, called Sashiko no fukuro mono (Sashiko Bags - Amazon Japan affiliate link)), was published by Ondori in 1998 and written by Eiko Yoshida, who you may remember I mentioned before as being my teacher’s teacher. Eiko Yoshida (1922-2002) was born in Honjo, Akita prefecture, and helped created a boom in the revival of sashiko’s popularity in the late twentieth century. Akita sashiko is noted for the use of colorful thin silk thread and single cotton thread, and Eiko herself was apparently born into a family with a Japanese-style clothing business, so perhaps these factors combined account for the sense of style and design she is known for. Ei Rokusuke, a well-known writer, radio and TV personality used to wear a sashiko hanten (padded jacket) stitched by Eiko for stage appearances. You can certainly see an artistic and discerning aesthetic behind the designs featured in this book. She writes in the introduction (p.1): “I created sashiko bags with traditional Japanese patterns and a fresh sensibility. Items made according to the age-old practice of stitching indigo cotton with white thread have a soothing elegance. But these same traditional patterns can give rise to new expression through fabric, thread and design. The beautiful 20cm by 17cm drawstring bag pictured below is ample illustration of that. The next four pages then show 96 design variations for this same bag! The variation in sashiko patterns, colours and arrangements of designs is simply amazing. What a cornucopia to take inspiration from. I admit I haven’t made this bag, but the instructions given on page 36 don’t look too difficult. I make no guarantee, but a skilled seamstress would possibly be able to work out what to do from the diagrams even if you can’t read the Japanese. It requires a piece of cloth 52cm by 19cm, lining 42cm by 19cm, 100cm cord, and thread for the sashiko. If anybody does attempt it, please let me know. Only the design template for the bag pictured on page 1 is given, all the rest you would have to find for yourself, or even better, create your own! There are many other types of bags in this book – shoulder bags, handbags, glasses cases and various types of kinchaku – with to-die for designs and instructions for making (all in Japanese), and after flicking through it yet again, I can feel a bag fetish coming on.

2 Comments

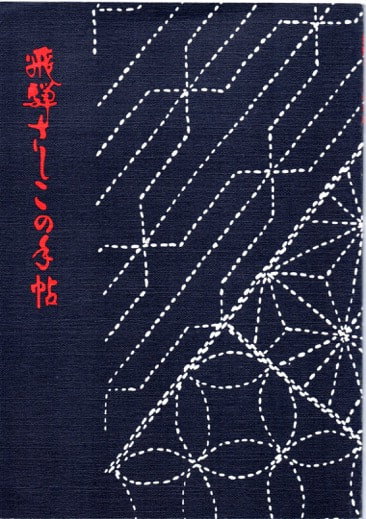

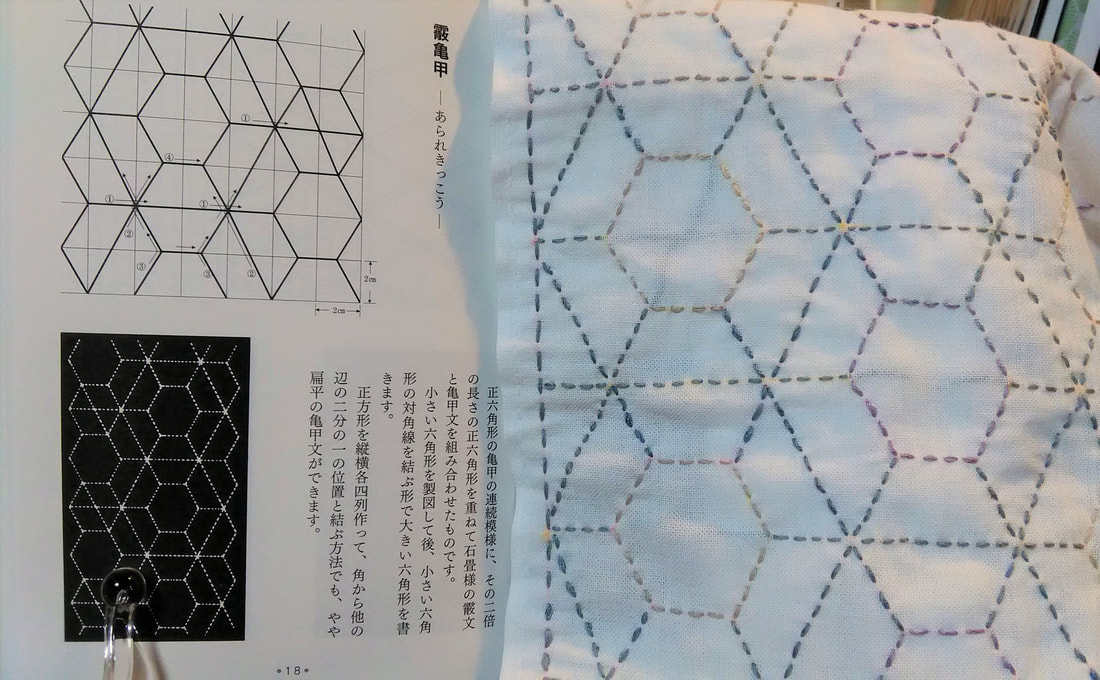

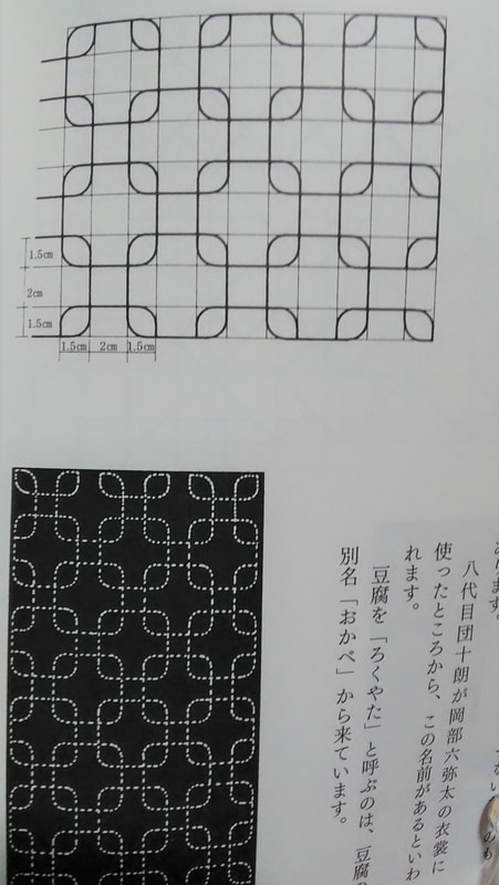

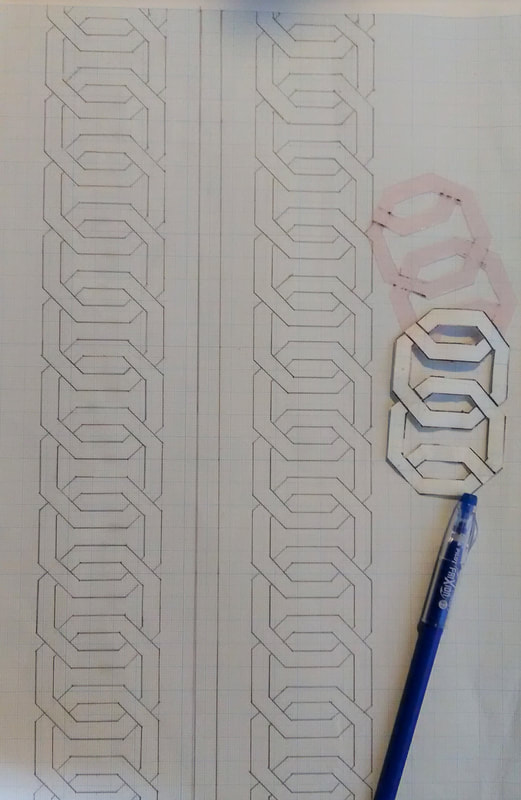

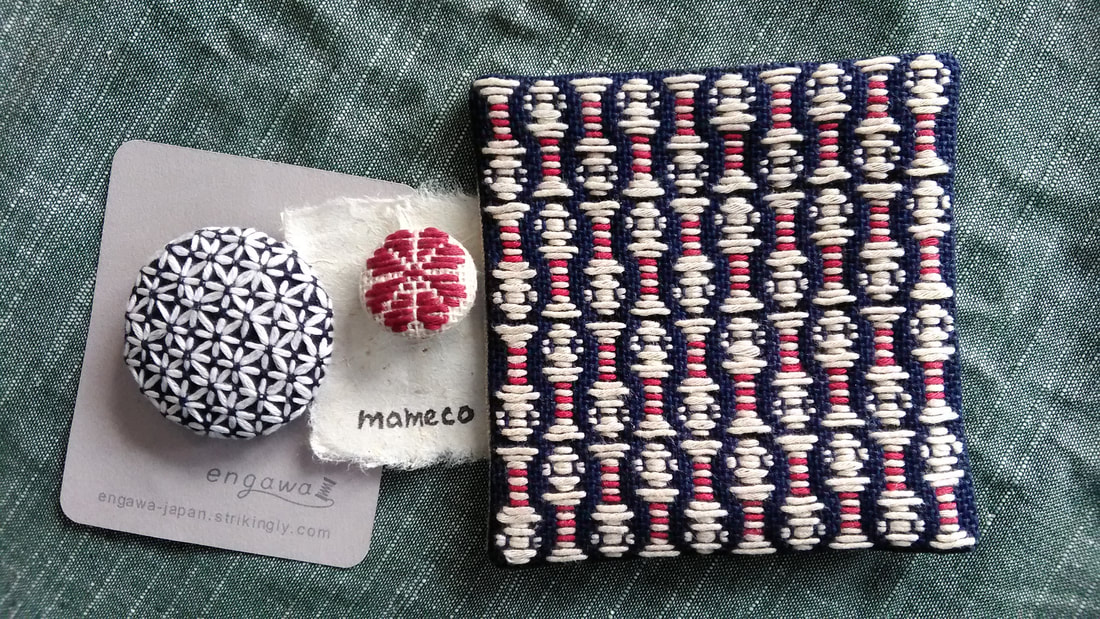

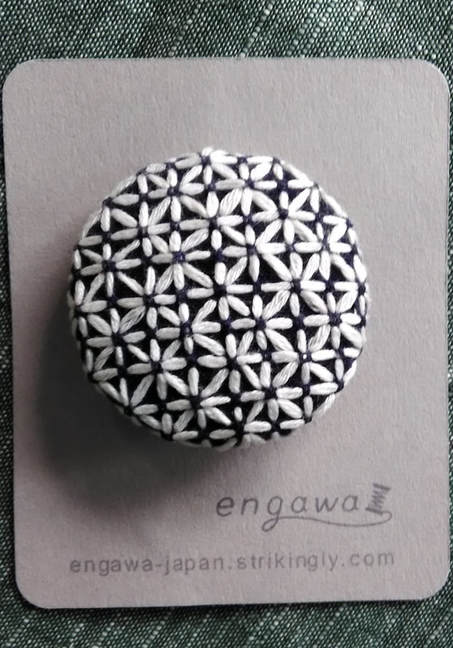

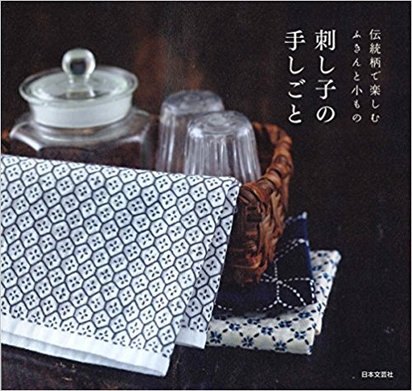

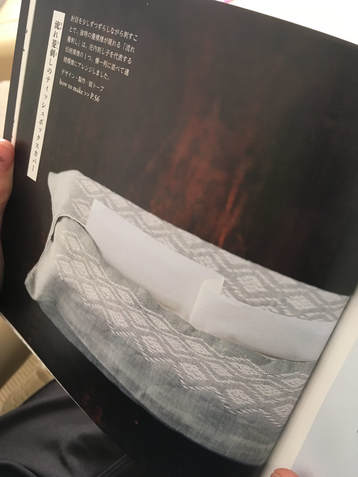

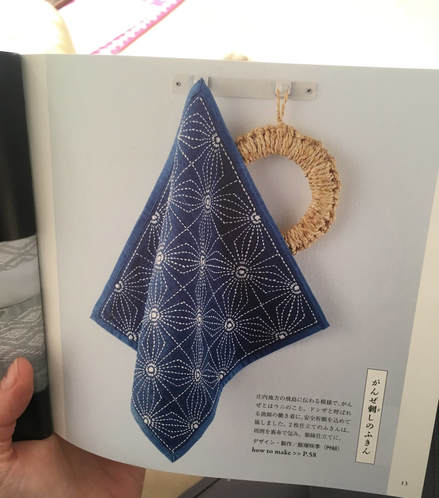

When I visited the Hida Sashiko exhibition last year I purchased a small book called Hida Sashiko no Techo (The Hida Sashiko Notebook, by Reiko Futatuya, first released in 1978, reprinted 2013, published by Hida Sashiko), as I always do whenever I come across a book about sashiko that’s not in my collection. Every book has its own appeal, and I never tire of looking through my collection and taking in the variety of sashiko styles and applications. Anyway, by today’s standards this book is very simple; thirty three pages in mostly black and white, and basically just a reference for patterns, but in 1978 when it was first published I doubt there were many books about sashiko available, so I am sure it would have been a valuable resource. (Still is, actually. I found it referred to less than a year ago on this blog, which is written in Japanese, but the photographs are lovely.) As with most such books there is a general description of sashiko’s roots in reusing and reinforcing cloth, but I liked the concrete examples given; for example stitching the tabi (socks) worn by the boatmen transporting lumber down the river to make the sole non-slip in the water; or stitching a chrysanthemum motif in the in the corner of a furoshiki (wrapping cloth) to prevent knots coming undone. There’s a brief discussion of cloth (hemp, cotton and silk), thread and needles, and tools with the general advice of choosing the thread and needles to suit your purpose. All in all there are twenty-eight designs introduced, which the author says are a sample of those most commonly used in Hida, and are a mixture of hitomezashi (one stitch), and moyozashi (pattern sashiko). Each design has a simple explanation of the name, composition and roots, and shows the dimensions on graph paper so that the patterns can be reproduced and adapted. Most of the patterns were familiar, as I had seen them before in various forms in other sashiko books, but I did find a couple that were completely new to me. One was Roku Yata goshi (Roku Yata lattice), so-called because it was used on the costume of a popular kabuki actor in the early 19th century when he played the role of a samurai called Roku Yata, and the pattern became hugely fashionable. Another was Yoshiwara tsunagi, (linked Yoshiwara) a series of linked octagons, which I have seen printed on towels and clothing but never as sashiko. According to this book it is often used for actors and dancers stage costumes. Further research led me to discover that it was used on the curtains of teahouses in the red-light Yoshiwara district in Edo, hence the name Yoshiwara. For some reason this design struck a chord in me; I love the suggestion of strength and complexity, in a compact simple line – and felt compelled to make something with it, so I stitched it onto the back of my jeans jacket. When Reiko Futatuya wrote that she hoped these patterns would be used for new fabrics and purposes, I don’t expect she imagined this! I was in Sendai recently with a couple of hours to spare, so I set out to see what I could find in the way of sashiko in the centre of the city. Sendai is the capital city of Miyagi Prefecture, part of the northern region of Japan known as Tohoku, where the three main types of sashiko originated. Shonai sashiko (of which hitomezashi is typical) comes from Yamagata prefecture, on the eastern border of Miyagi, while kogin sashiko and nanbu hishizashi originated in Aomori prefecture, which is north of Miyagi but with Iwate prefecture in between. I didn’t have to go very far to make my first discovery. Less than a hundred metres from my hotel I found TRY6, a community-sponsored business incubator shop for local entrepreneurs, where my eyes were immediately drawn to a couple of shelves with a beautiful display of small items such as brooches, buttons and hair-ties stitched with kogin and Shonai sashiko. These were the work of an artist whose needle name is engawa. I couldn’t resist buying a charming brooch of white komenohana zashi (rice flower) stitched on indigo-dyed cloth. According to engawa's website, s/he was born in Hokkaido, lives in Sendai, and has been stitching sashiko items since 2013. Take a look at this link (in Japanese) to see more of engawa’s delightful creations. “minne” and “creema”, by the way, are online Japanese shops. The helpful manager in TRY6 gave me a tip about another gallery he thought might have some sashiko, and sure enough when I reached the galerie arbre, I discovered the work of two more sashikoists. Kogin mameco, the needle name of a lady who specializes in kogin sashiko, had a lovely range of book covers, zip pouches and pencil cases on display. Once again, however, I couldn’t resist the brooches, and purchased a sweet button-sized brooch covered in a rough-weave beige cloth stitched with a red ume no hana (plum flower). See Kogin mameco’s work here. Hitomezashi and kogin sashiko are currently extremely popular in Japan, so I was not surprised that all the sashiko I had found so far was exclusively in those two styles. The sashikoist known as harinoto, who lives in Tochigi prefecture (which is not Tohoku) and whose work I also discovered in galerie arbre, however, was doing something quite original with kogin. Harinoto had made a series of coasters representing the six prefectures in Tohoku, stitched with a kogin-style motif emblematic of each prefecture. These were apples for Aomori, iron tea-pots for Iwate, woven straw horses for Akita, wooden kokeshi dolls for Miyagi, cherries for Yamagata, and toy red cows for Fukushima. Naturally I bought a kokeshi doll coaster as a souvenir of my visit to Miyagi. I tracked down harinoto’s blog and found that she has also published a book about kogin sashiko. Koginzashi moyo asobi (Playing around with kogin sashiko patterns) Nihon Vogue, 2016 (Amazon Japan affiliate link) All in all it was a very pleasant and satisfying way to while away a few hours, walking around the backstreets of Sendai in search of sashiko!  Coasters by harinoto Coasters by harinoto I’ve been busy getting the online shop ready and haven’t had much time for writing recently (or doing sashiko!), but here’s a review of a book I wanted to tell you about. Also, if you haven’t already ordered, don’t forget to take a look at the three-kit subscription set I’m taking orders for at the moment in my shop.. Anyway, the latest addition to my collection of sashiko books is this neat little volume published by Nihon Bungeisha in October. Sashiko no Teshigoto (Sashiko Handiwork - Amazon Japan affiliate link) is a collection of beautifully photographed fukin and other small handiwork items — such as a tissue box cover, purse, bag and coasters — with instructions on how to make them. As so often happens, when I bought this book and flicked through I immediately wanted to make everything, which of course I don’t have time for. But even if that’s not possible, I still get a lot of enjoyment from simply looking at photographs of beautiful sashiko stitching, and in that respect this book is very satisfying. It could easily be a coffee table book as the photography is lovely. The sashiko handiwork is displayed on mostly dark wood or light backgrounds, in tasteful minimalist settings with only an iron teapot or cane basket as an accent, and the overall effect is traditional yet modern, an accurate reflection of the sashiko items themselves: conventional but with an elegant, contemporary touch. For example, the white hanafukin with a cross flower stitch in charcoal grey, and one red flower in the corner. Or the chic tissue box cover with nagare hishizashi stitched in white on pale grey cotton. One reason I like this book is that it retains an emphasis on the traditional blue and white combination, while offering an updated version with subtle variations on that theme. As with many sashiko books it follows a standard format of introducing a number of sample pieces (in this case twenty), then providing samplers of the stitches, basic instructions on how to do sashiko (with explanations about cloth, thread, equipment, drafting, stitching and making two easy pieces), and instructions for making up each individual item. The stitches are introduced in four categories; straight line patterns such as tobi asanoha (scattered hemp leaf), curved line patterns such as fundo tsunagi (linked weights), hitomezashi such as kaki no hana (persimmon flower), and Shonai sashiko such as ganzezashi (sea urchin stitch). The last, ganzezashi, is one of my most favourite stitches. It could have something to do with the fact that sea urchin is my favourite sushi topping… but I also love the convergence of concentric lines that scream out to me sashiko! Stitched in white on blue cloth, this hanafukin is totally mesmerizing. Next to making it myself, a photograph is the next best thing.

|

Watts SashikoI love sashiko. I love its simplicity and complexity, I love looking at it, doing it, reading about it, and talking about it. Archives

September 2022

Categories

All

Sign up for the newsletter:

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed