|

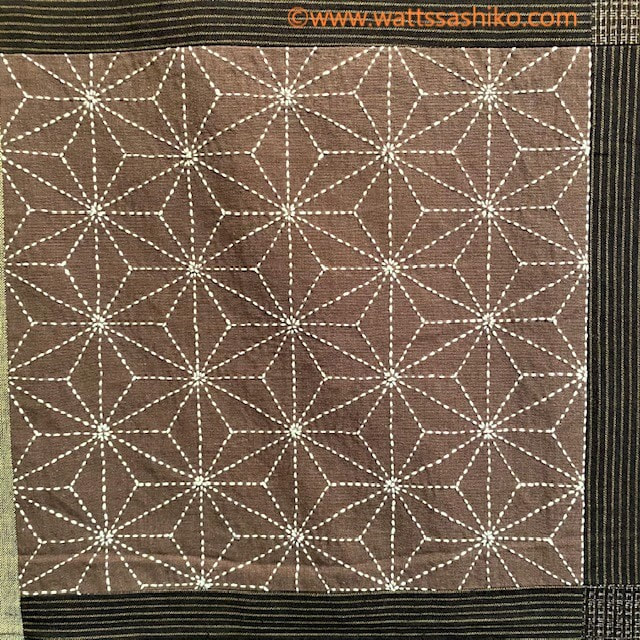

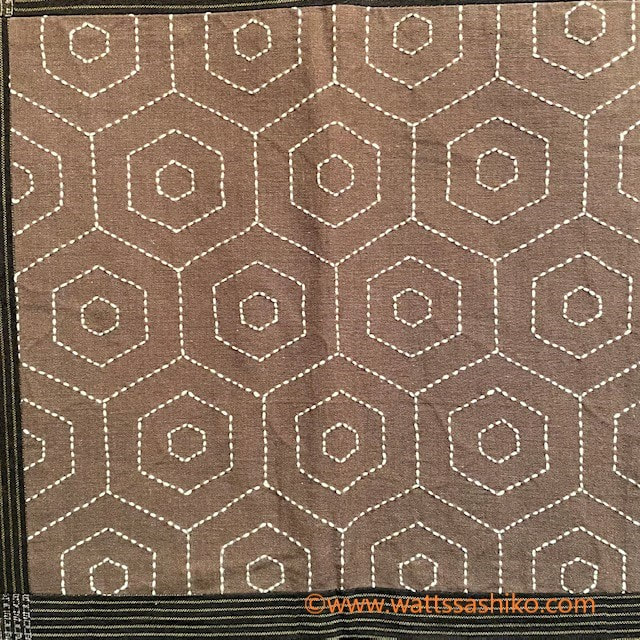

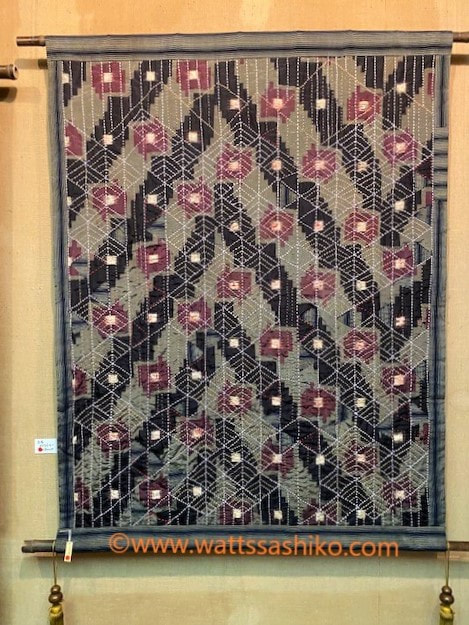

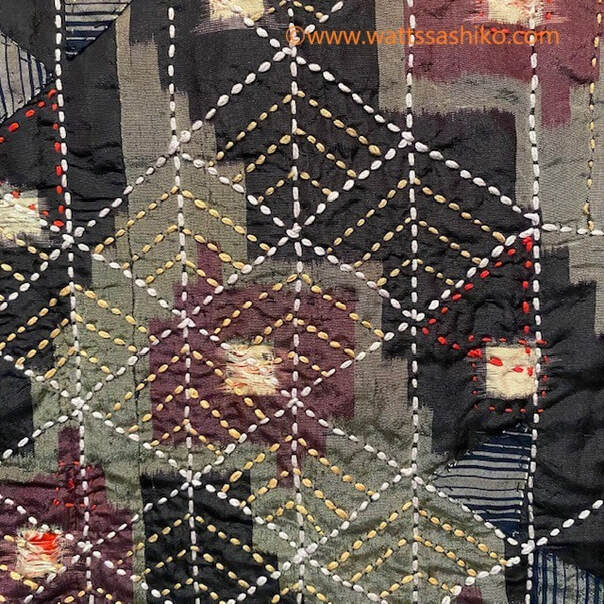

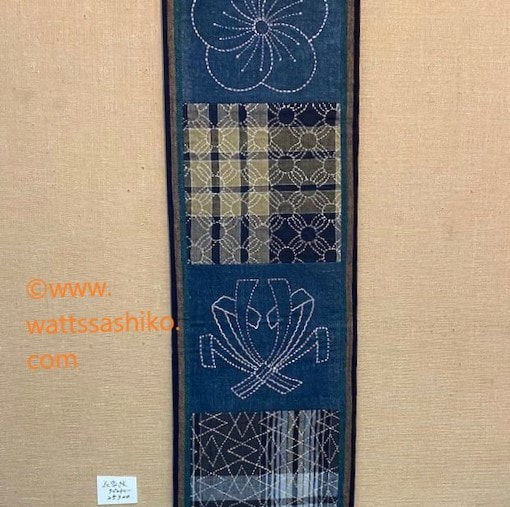

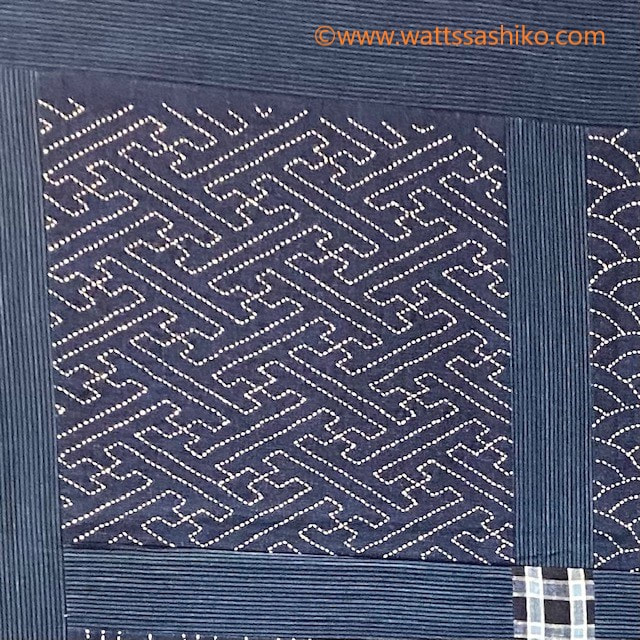

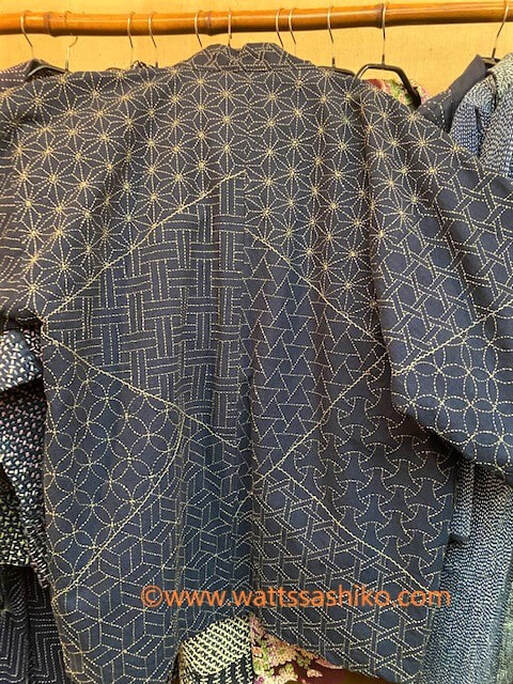

The pandemic has made it hard for many businesses, and sashiko is no exception. When I went to see the travelling Hida Sashiko exhibition recently, I heard that the Takayama-based Hida Sashiko company, too, was struggling. With domestic travel limited, not to mention the states of emergency, business hours are shortened and there is not enough work for staff. Travelling exhibitions like this are an important method of selling their range of sashiko clothing, hangings and bags etc., but the cancellation of many regular dates, such as at department stores, have also hit hard. I’m glad the Yokose Gallery, where I saw the exhibition, was open for business as usual. I have written about my visits to this exhibition before. This is where I discovered the Hida Sashiko Notebook, which continues to be a valuable reference source for me. This year, Notebook in hand, I went looking for examples of patterns from it in the exhibition. This wall hanging yielded several to check off the list straight away. Below are close ups of six patterns from the Notebook This hanging made from old fabric is stitched with diamond blue wave (hishi seigaiha), which creates the impression of waters more turbulent than the round blue wave pattern. On another wall hanging I found circular seven treasures (maru shippo). The overlapping point of four circles creates another small circle. Circles represent harmony and this pattern has come to be associated with good fortune. The seven treasures--gold, silver, lapis lazuli, crystal, agate, coral and clams--comes from Buddhism. This entrance curtain is worked with Japanese cypress (higaki) pattern, a geometric stylization of the interleaved cypress panels used on ceilings, fencing and wainscotting. This bag incorporates a pattern based on the wooden counting rods (sankuzushi) of a tool once used for Japanese-style calculations and divinations. Another paneled wall hanging netted a few more patterns. Sayagata, which I have seen variously translated as key fret, saya pattern, saya brocade, is based on the a diagonal version of the swastika pattern, and which was often seen on Chinese brocade. Rising steam (tatewaku) is self explanatory I think. Of the 29 patterns in the Hida Notebook, I managed to find twelve, but there were probably more tucked away amongst the many hangings, bags, coats and other items on display. To finish, here are a couple of my favourite pieces. The first is a hanten, a traditional warm jacket with a glorious selection of patterns, and the other is an example of long jacket with a pattern called donza which is based on seaweed and originated on the small fishing island of Tobishima in the Japan Sea. The items in the exhibition are not for sale online, but sashiko kits and supplies are available at the online shop.

4 Comments

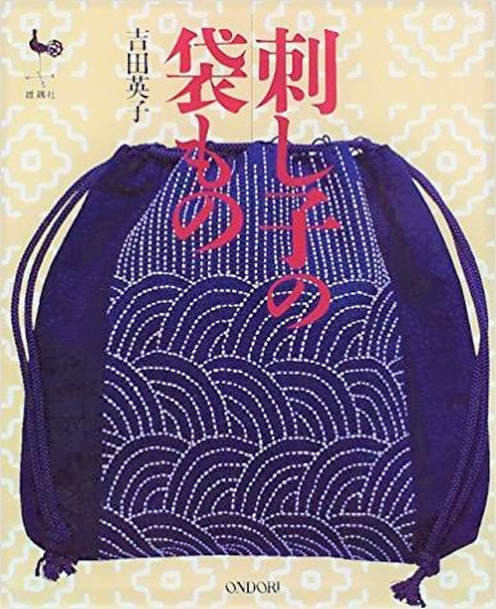

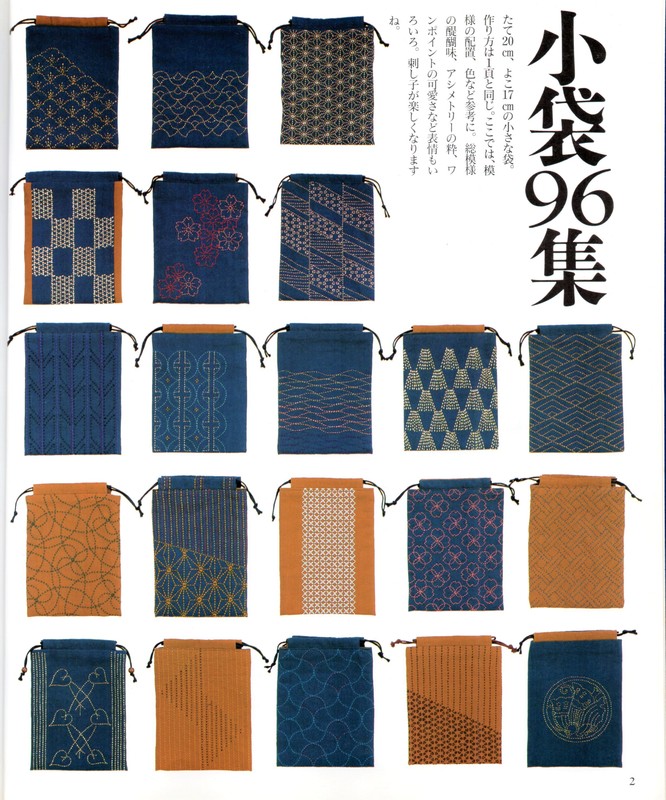

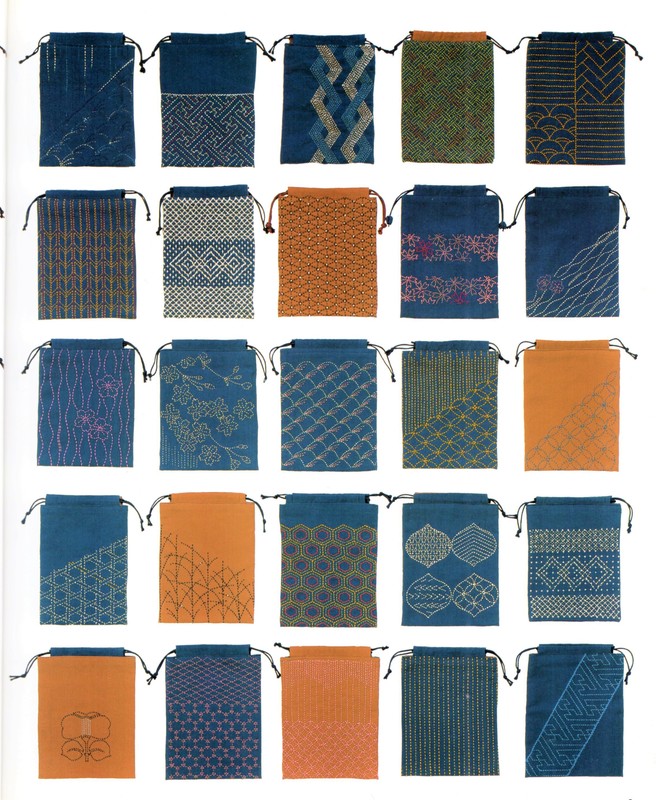

After writing in my last post about the exquisite kinchaku bag I received, I felt like revisiting a book in my collection featuring kinchaku and other bags. This book, called Sashiko no fukuro mono (Sashiko Bags - Amazon Japan affiliate link)), was published by Ondori in 1998 and written by Eiko Yoshida, who you may remember I mentioned before as being my teacher’s teacher. Eiko Yoshida (1922-2002) was born in Honjo, Akita prefecture, and helped created a boom in the revival of sashiko’s popularity in the late twentieth century. Akita sashiko is noted for the use of colorful thin silk thread and single cotton thread, and Eiko herself was apparently born into a family with a Japanese-style clothing business, so perhaps these factors combined account for the sense of style and design she is known for. Ei Rokusuke, a well-known writer, radio and TV personality used to wear a sashiko hanten (padded jacket) stitched by Eiko for stage appearances. You can certainly see an artistic and discerning aesthetic behind the designs featured in this book. She writes in the introduction (p.1): “I created sashiko bags with traditional Japanese patterns and a fresh sensibility. Items made according to the age-old practice of stitching indigo cotton with white thread have a soothing elegance. But these same traditional patterns can give rise to new expression through fabric, thread and design. The beautiful 20cm by 17cm drawstring bag pictured below is ample illustration of that. The next four pages then show 96 design variations for this same bag! The variation in sashiko patterns, colours and arrangements of designs is simply amazing. What a cornucopia to take inspiration from. I admit I haven’t made this bag, but the instructions given on page 36 don’t look too difficult. I make no guarantee, but a skilled seamstress would possibly be able to work out what to do from the diagrams even if you can’t read the Japanese. It requires a piece of cloth 52cm by 19cm, lining 42cm by 19cm, 100cm cord, and thread for the sashiko. If anybody does attempt it, please let me know. Only the design template for the bag pictured on page 1 is given, all the rest you would have to find for yourself, or even better, create your own! There are many other types of bags in this book – shoulder bags, handbags, glasses cases and various types of kinchaku – with to-die for designs and instructions for making (all in Japanese), and after flicking through it yet again, I can feel a bag fetish coming on.

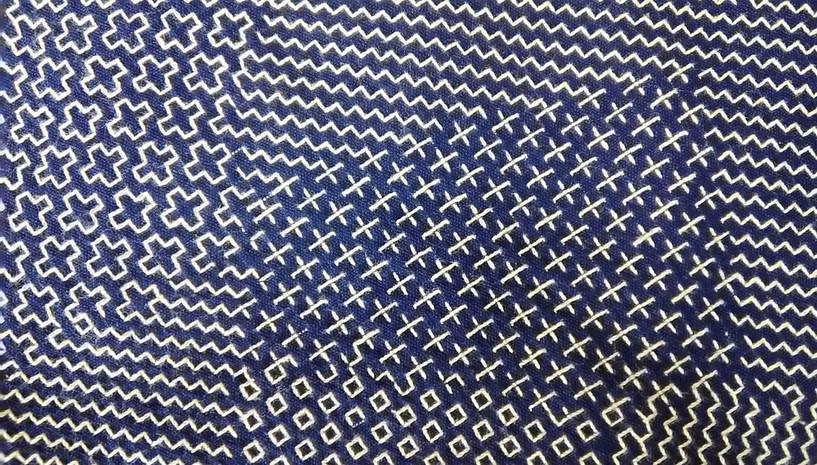

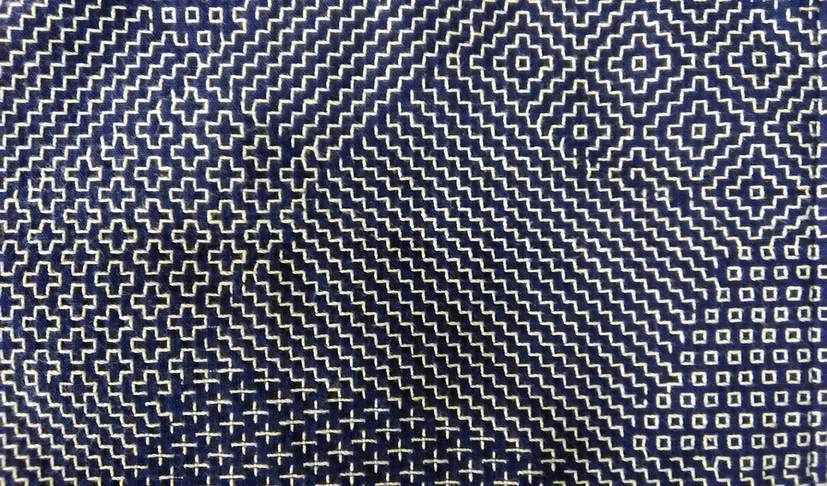

Imagine my delight when the postman delivered me a package recently, and I opened it up to find this gorgeous drawstring bag inside, a gift from an acquaintance who thought I could appreciate it. And she was right! I oohed and aahed with admiration as I examined it every from angle, resisting the temptation to unpick the beautiful red lining and peek at the underside. This type of bag, called a kinchaku in Japanese, was—and still is--used to carry around valuables or personal effects. Although an accessory for Japanese-style clothing, and probably not as common as it once used to be now that Western dress is the norm, it is nevertheless, far from having fallen out of use. I often see the elderly ladies in my neighborhood out for a daily walk clutching their kinchaku. And schoolchildren keep stationery, or implements for school lunches in these bags, though they are far more likely to be decorated with cute characters than sashiko. At summer festivals kinchaku are a common accessory for traditional festival wear, in fact I have a fancy red one to go with my yukata (cotton summer kimono). Naturally cloth kinchaku are ideal for sashiko, and the choice of pattern can indicate anything from seasonal themes to protection from evil spirits or wishes for a long life, or simply a something that catches the maker’s fancy! I’m not sure what dictated the maker’s choice of patterns for my new kinchaku, but it is stitched with a selection of five hitomezashi patterns, typical of the Shonai region in Yamagata prefecture. These are: two types of jujizashi (cross stitch), yamagata (mountain form), sanju kakinohanazashi (triple persimmon flower stitch) and kuchizashi (mouth stitch). I love the way the blocks merge without any border between them. And I am awed by the quality of stitching, which is just incredible! Every stitch is so perfectly aligned and neat you would almost think it was done by machine, but of course that is impossible. Owning this bag will certainly be an inspiration to me to up my game. I am almost embarrassed to post the picture of the one and only kinchaku that I’ve ever made. I find it very useful for holding all the thread, needles and tools together for whatever sashiko project I have on the go, but it’s such a handy item I often divert it for other purposes as well, so making more is on my list of items to do. In the meantime I have my lovely new kinchaku, but I don’t want to spoil it with knockabout use so I’m still deciding what to use it for. One thing I know; I will walk a little straighter when I carry this beautiful bag on me.

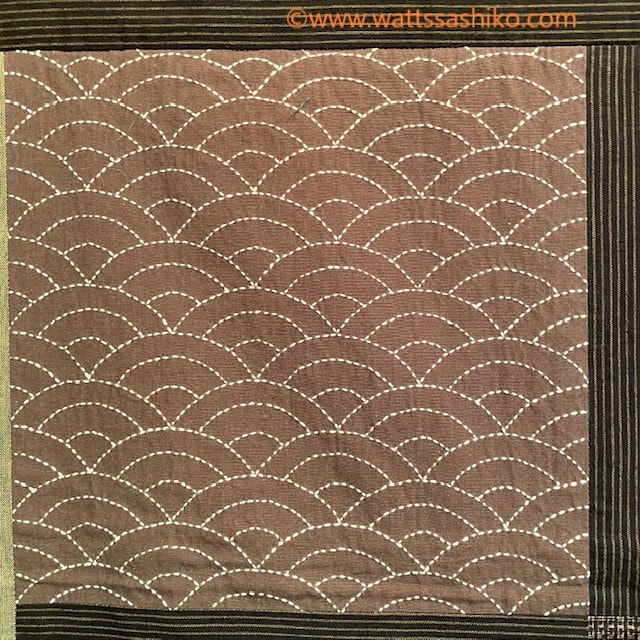

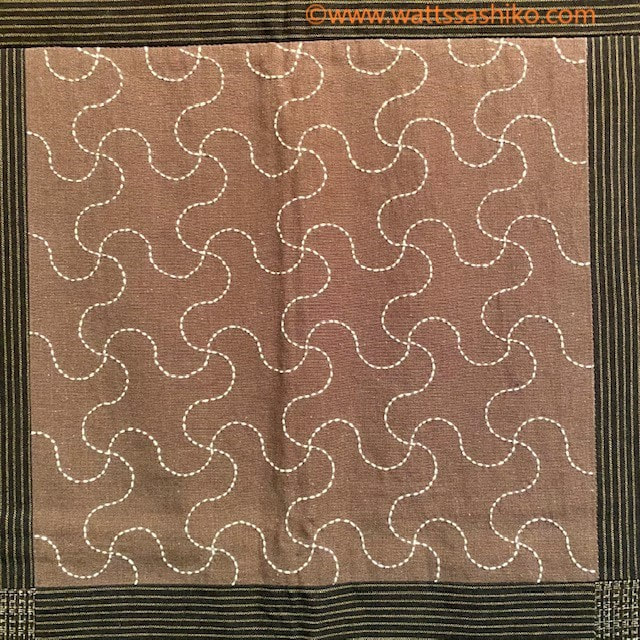

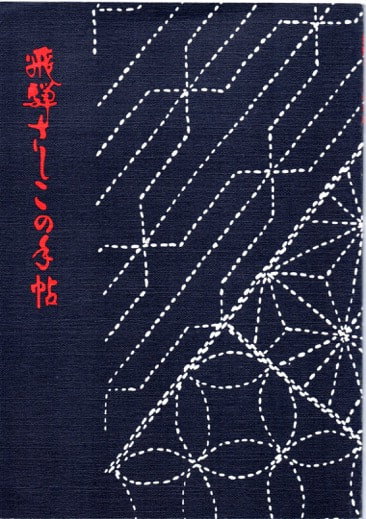

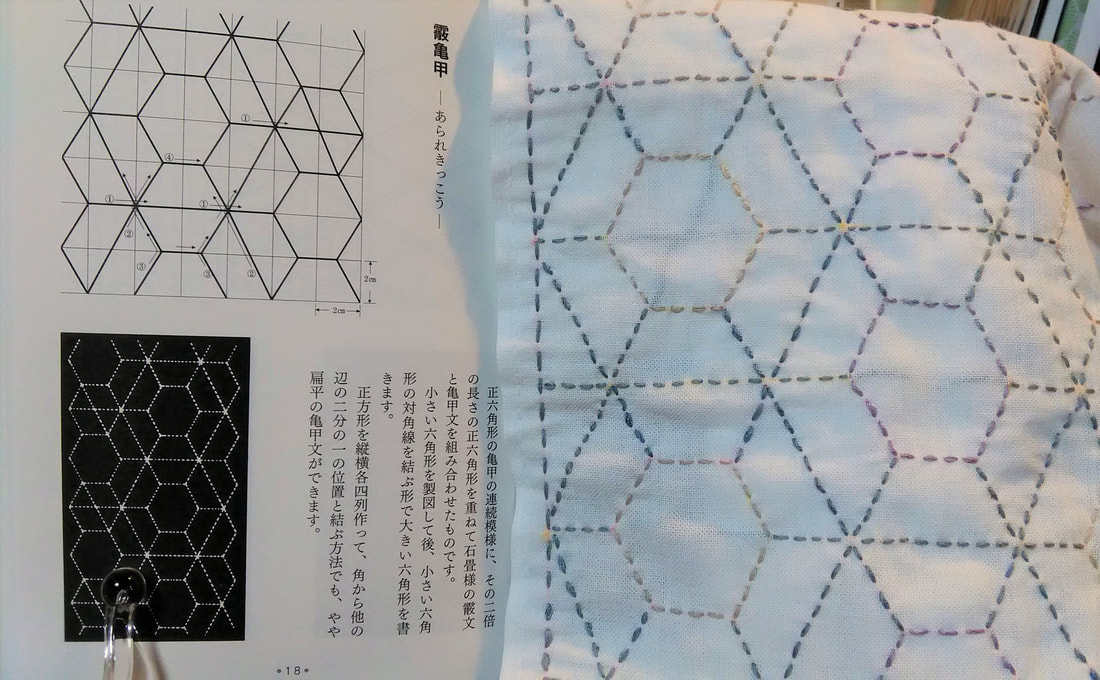

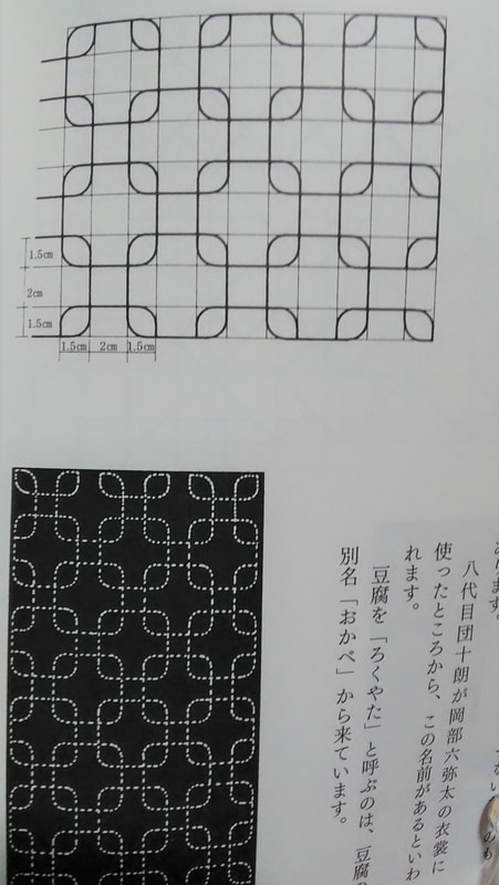

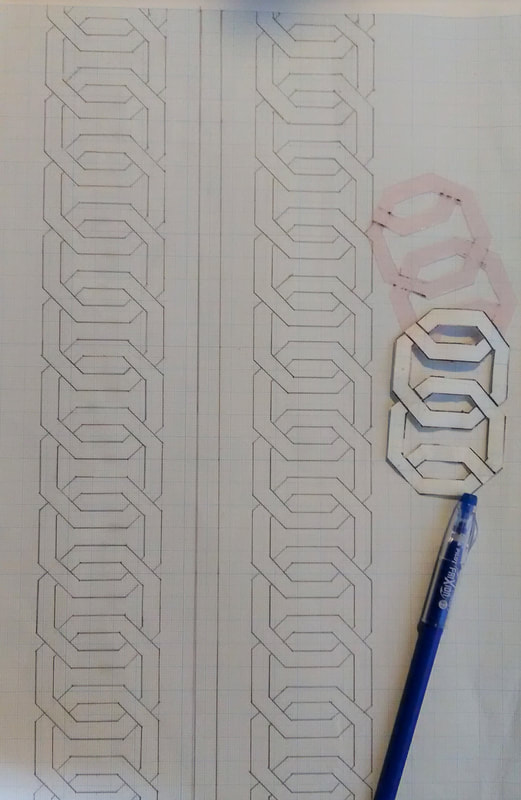

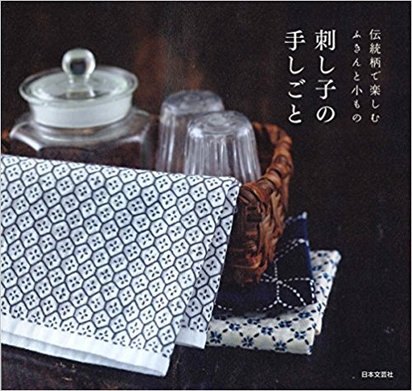

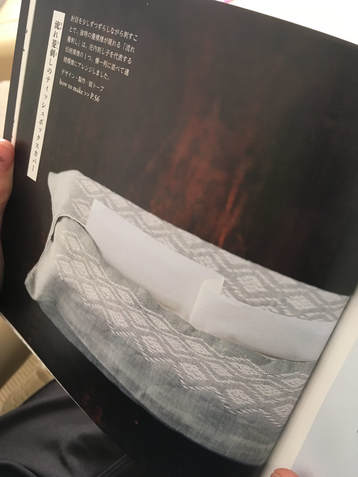

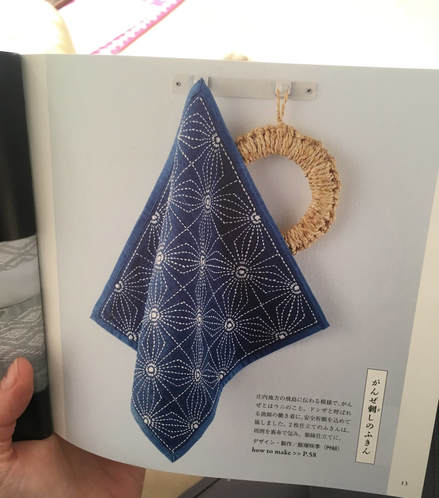

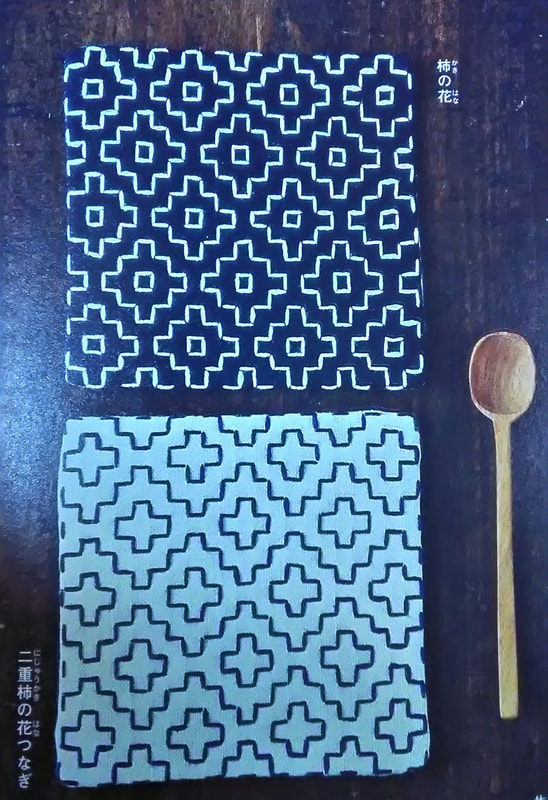

When I visited the Hida Sashiko exhibition last year I purchased a small book called Hida Sashiko no Techo (The Hida Sashiko Notebook, by Reiko Futatuya, first released in 1978, reprinted 2013, published by Hida Sashiko), as I always do whenever I come across a book about sashiko that’s not in my collection. Every book has its own appeal, and I never tire of looking through my collection and taking in the variety of sashiko styles and applications. Anyway, by today’s standards this book is very simple; thirty three pages in mostly black and white, and basically just a reference for patterns, but in 1978 when it was first published I doubt there were many books about sashiko available, so I am sure it would have been a valuable resource. (Still is, actually. I found it referred to less than a year ago on this blog, which is written in Japanese, but the photographs are lovely.) As with most such books there is a general description of sashiko’s roots in reusing and reinforcing cloth, but I liked the concrete examples given; for example stitching the tabi (socks) worn by the boatmen transporting lumber down the river to make the sole non-slip in the water; or stitching a chrysanthemum motif in the in the corner of a furoshiki (wrapping cloth) to prevent knots coming undone. There’s a brief discussion of cloth (hemp, cotton and silk), thread and needles, and tools with the general advice of choosing the thread and needles to suit your purpose. All in all there are twenty-eight designs introduced, which the author says are a sample of those most commonly used in Hida, and are a mixture of hitomezashi (one stitch), and moyozashi (pattern sashiko). Each design has a simple explanation of the name, composition and roots, and shows the dimensions on graph paper so that the patterns can be reproduced and adapted. Most of the patterns were familiar, as I had seen them before in various forms in other sashiko books, but I did find a couple that were completely new to me. One was Roku Yata goshi (Roku Yata lattice), so-called because it was used on the costume of a popular kabuki actor in the early 19th century when he played the role of a samurai called Roku Yata, and the pattern became hugely fashionable. Another was Yoshiwara tsunagi, (linked Yoshiwara) a series of linked octagons, which I have seen printed on towels and clothing but never as sashiko. According to this book it is often used for actors and dancers stage costumes. Further research led me to discover that it was used on the curtains of teahouses in the red-light Yoshiwara district in Edo, hence the name Yoshiwara. For some reason this design struck a chord in me; I love the suggestion of strength and complexity, in a compact simple line – and felt compelled to make something with it, so I stitched it onto the back of my jeans jacket. When Reiko Futatuya wrote that she hoped these patterns would be used for new fabrics and purposes, I don’t expect she imagined this! I’ve been busy getting the online shop ready and haven’t had much time for writing recently (or doing sashiko!), but here’s a review of a book I wanted to tell you about. Also, if you haven’t already ordered, don’t forget to take a look at the three-kit subscription set I’m taking orders for at the moment in my shop.. Anyway, the latest addition to my collection of sashiko books is this neat little volume published by Nihon Bungeisha in October. Sashiko no Teshigoto (Sashiko Handiwork - Amazon Japan affiliate link) is a collection of beautifully photographed fukin and other small handiwork items — such as a tissue box cover, purse, bag and coasters — with instructions on how to make them. As so often happens, when I bought this book and flicked through I immediately wanted to make everything, which of course I don’t have time for. But even if that’s not possible, I still get a lot of enjoyment from simply looking at photographs of beautiful sashiko stitching, and in that respect this book is very satisfying. It could easily be a coffee table book as the photography is lovely. The sashiko handiwork is displayed on mostly dark wood or light backgrounds, in tasteful minimalist settings with only an iron teapot or cane basket as an accent, and the overall effect is traditional yet modern, an accurate reflection of the sashiko items themselves: conventional but with an elegant, contemporary touch. For example, the white hanafukin with a cross flower stitch in charcoal grey, and one red flower in the corner. Or the chic tissue box cover with nagare hishizashi stitched in white on pale grey cotton. One reason I like this book is that it retains an emphasis on the traditional blue and white combination, while offering an updated version with subtle variations on that theme. As with many sashiko books it follows a standard format of introducing a number of sample pieces (in this case twenty), then providing samplers of the stitches, basic instructions on how to do sashiko (with explanations about cloth, thread, equipment, drafting, stitching and making two easy pieces), and instructions for making up each individual item. The stitches are introduced in four categories; straight line patterns such as tobi asanoha (scattered hemp leaf), curved line patterns such as fundo tsunagi (linked weights), hitomezashi such as kaki no hana (persimmon flower), and Shonai sashiko such as ganzezashi (sea urchin stitch). The last, ganzezashi, is one of my most favourite stitches. It could have something to do with the fact that sea urchin is my favourite sushi topping… but I also love the convergence of concentric lines that scream out to me sashiko! Stitched in white on blue cloth, this hanafukin is totally mesmerizing. Next to making it myself, a photograph is the next best thing.

Where has the time gone? While sashiko is never far from my mind, in this busy modern life it takes some planning to get me sitting in front of the computer long enough to actually write about it.

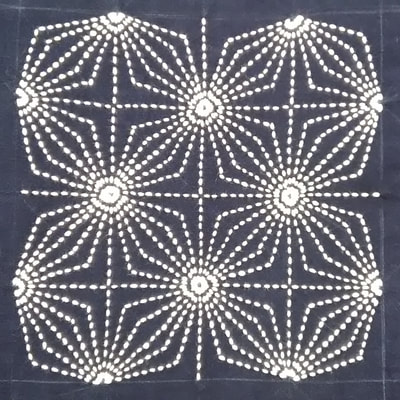

One tidbit of sashiko related news I wanted to tell you about was the announcement of the uniform for the Japanese soccer team in next year’s World Cup… featuring sashiko in the design. Next year will mark the twentieth anniversary since Japan first qualified to compete in the World Cup, so the concept is that sashiko will be the thread that connects up history. Isn’t that a nice idea! Speaking of sashiko connecting people, you may remember I previously wrote about visiting a tiny backstreet bar in Tokyo where the owner showed me hanafukin made by her 94-year-old mother-in-law (turns out it was mother-in-law, not mother). Well, the other day when I paid another visit I had a wonderful surprise; apparently the mother-in-law was so thrilled to hear about my visit, she sent me a little gift, two hanafukin that she had made. I was moved to tears, as never in my life did I expect to receive a hanafukin from my own mother, let alone anyone else’s! Another lovely surprise was that she had left me some other hanafukin to look at, one of which happened to be exactly the same pattern as the piece I was carrying around with me to work on, and my topic for today kaki no hana (persimmon flower).

This stitch is one kind of hitomezashi (one stitch sashiko), which you may recall I wrote before was traditionally often used for practical purposes, such as clothing or reinforcing material, because of the strength that the dense stitching imparts. Hitomezashi is typical of Shonai sashiko, one of the three major styles of sashiko. The Shonai region is Yamagata prefecture in northern Japan, a mountainous region, cold in winter, that faces the Japan Sea. The story goes that ships carried out regional products such as safflower and rice, and made the return journey with their holds filled with cotton and old clothing from the warmer regions they visited where cotton grew. Women would get busy stitching the cloth to make jackets, footwear and other useful items.

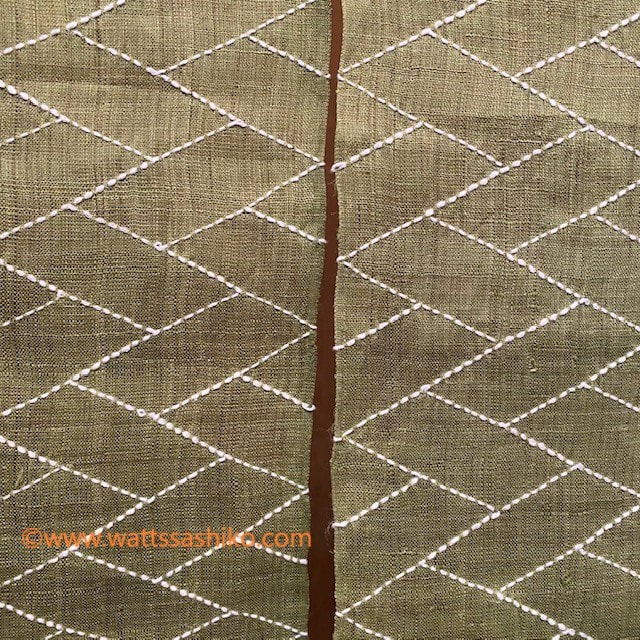

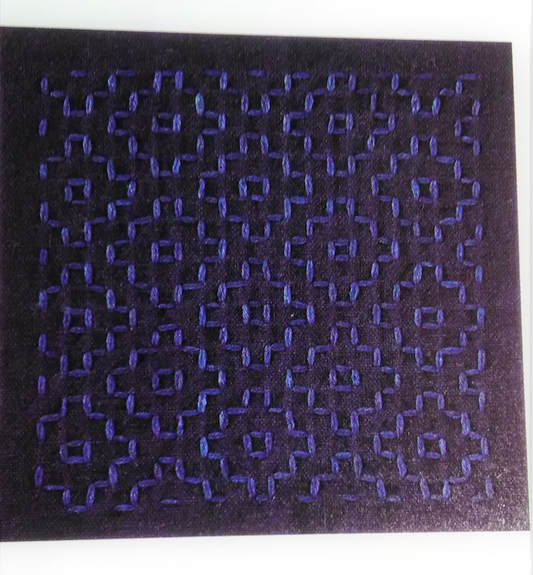

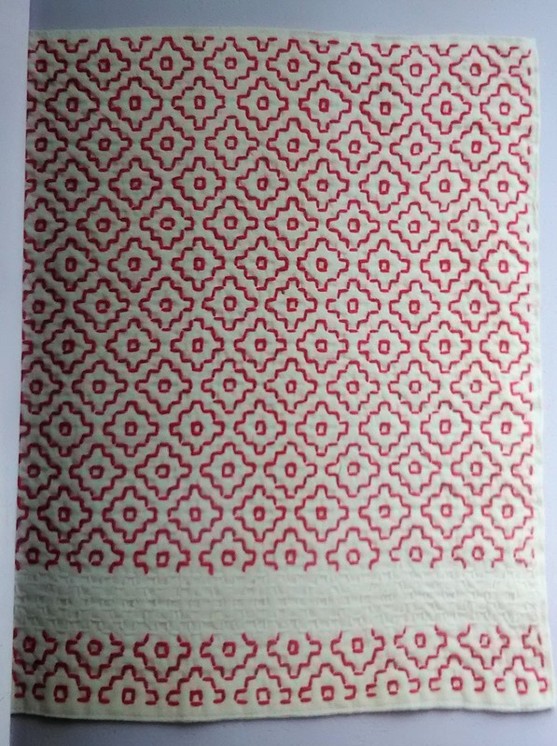

Compared to moyozashi (pattern stitches), I find hitomezashi easy in the sense that you don’t have to think about the length of your stitches or making them fit them the pattern, because each stitch is simply one side of a square in the grid. The only tricky thing is that you have to get the order of stitching right, if you don’t the pattern won’t appear. Transferring the pattern is simple too; just draw or trace a grid onto the fabric and off you go. The recommended size of the squares on the grid is 5mm, but they can be up to a centimeter. Any longer and the stitching will stick up or catch. Here’s some examples of kaki no hana stitching I found in my collection of sashiko books that may inspire you! (*Amazon Japan affiliate links included)

Above two images from Tohoku no Sashiko (Sashiko from the Tohoku region), Nihon Vogue-sha, 2016

Kawaii Hari Shigoto: Sashiko no Tezukurikomono (Charming Needlework: Small Handmade Sashiko Items), Boutique-sha, 2017

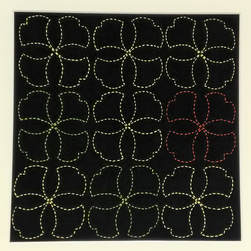

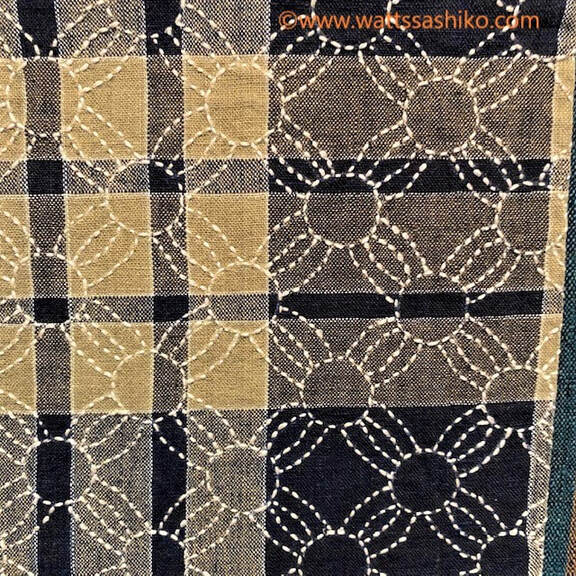

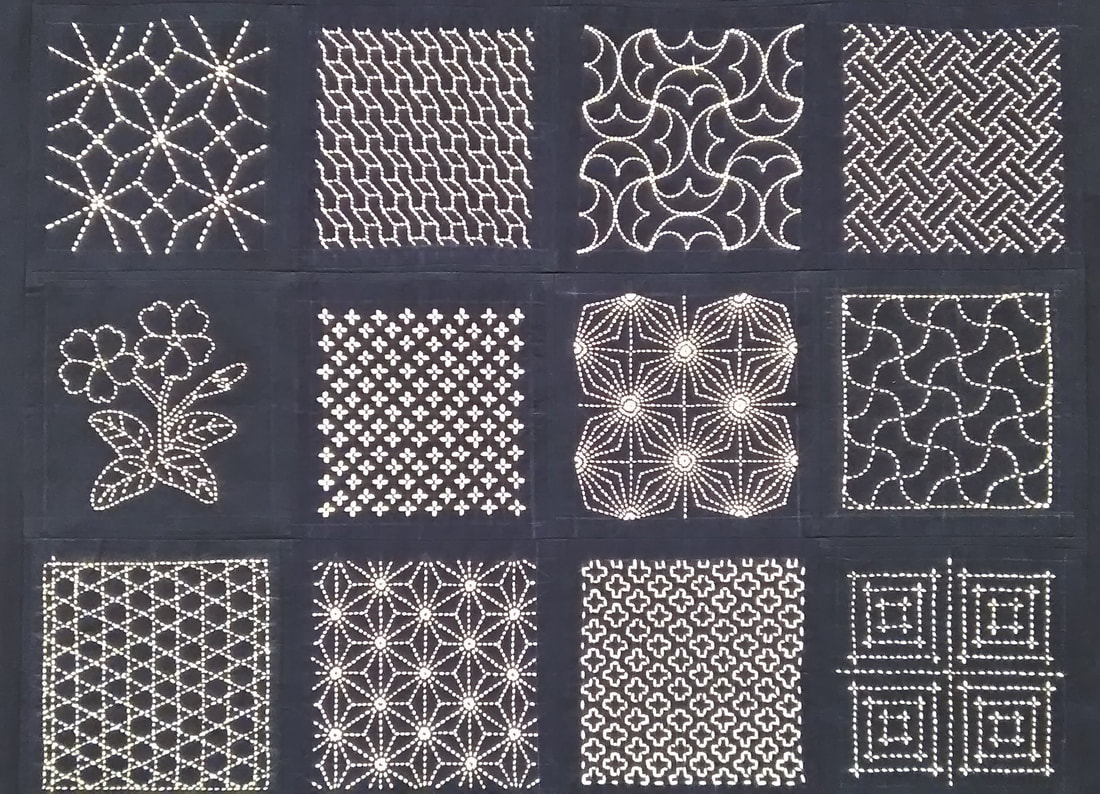

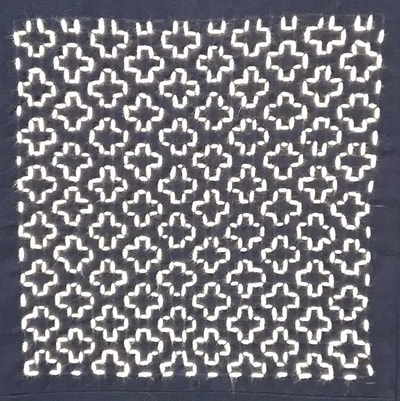

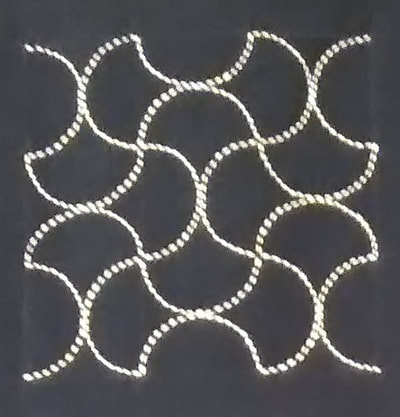

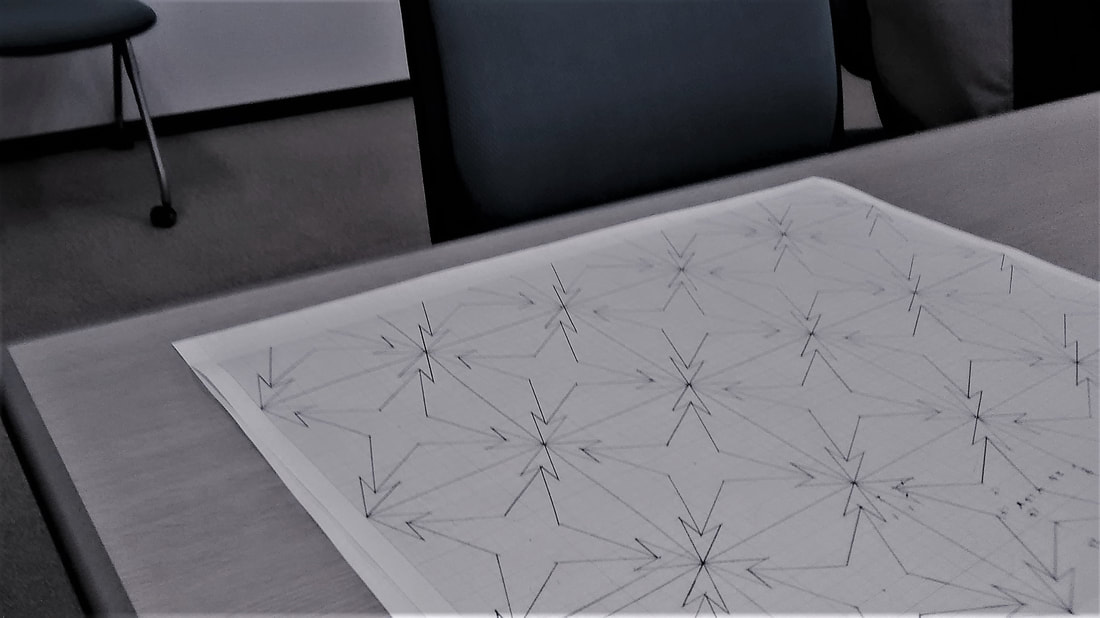

Last week my sashiko group participated in an annual exhibition held in the local Station Gallery. A train station might seem an unlikely location for a gallery, but actually it makes sense, as it’s the most central place in town and gets a lot of potential viewers passing by. Which happily was the case this time.  Icho tsunagi pattern (linked ginko leaves) Icho tsunagi pattern (linked ginko leaves) For the exhibition I decided to make another framed piece of sashiko to add to a series I started last year. This year I chose to stitch the pattern icho tsunagi, which means linked ginko leaves. As time was running short, I cheated by blowing up the pattern on a photocopier instead of enlarging the proportions on graph paper (shhh…don’t tell Sensei!). Then I cut and taped the paper pieces together to fit the cloth dimensions, taped chaco paper (transfer paper for tracing designs onto fabric) to the back of this pattern and traced over the design with a ballpoint pen to imprint it on the fabric. The autumn ginko leaves are gorgeous at this time of year and I wanted to reflect that by using thread in autumn colours of green and yellow, but unfortunately the result wasn’t as vivid as I hoped, so I ended up putting in one orange leaf for some contrast variation. Anyway, I was pleased with the result, and best of all Sensei praised my corner stitches. Phew! I didn’t want to let the side down… My fellow sashikoists all contributed their work from the past year and it was so exciting to see the inventive and wonderful pieces they’ve done all gathered in the one place. A real Aladdin”s cave! I had intended to describe these for you here, but realized I couldn’t possibly do them justice, so I’ll keep that for some later posts. The most thrilling exhibits, however, were the two wall hangings that were on display for the first time. Take a look at the amazing work below! These were the result of a joint project we’ve been working on all year, stitching squares fifteen by fifteen centimetres in length with whatever patterns we liked. When the time was up we gathered up all the squares and put them together to see what size hanging was possible. It turned out we had enough for two. Sensei gave no stipulations whatsoever as to what patterns we should stitch, but the overall balance seemed to be just right, and a lovely sampler of all the different styles of stitches; the densely stitched hitomezashi (single stitch), kyokusen moyozashi (curved line patterns), chokusen moyozashi (straight line patterns) and jiyuzashi (free stitching). I could look at these all day in wonder and never tire. What a gorgeous illustration of the beauty of sashiko!

I belong to a group of ten that meets once a month. Our teacher is Ms Chiyoko Nakazaki, who we call Nakazaki Sensei, as you do in Japanese. I know that in some classes the teacher provides the pattern, cloth and thread all cut up and ready to stitch, so that everybody does exactly the same thing, but Nakazaki Sensei’s approach is different. She encourages us all to find our own style and express our individuality through sashiko. However, she always stresses that in order to do this you must know the basics. Each month she gives us one or two different sashiko patterns to study. During the lesson we copy these onto graph paper, then mark up the fabric and begin stitching if time allows. We are free to choose how we want to apply the pattern. Sometimes Sensei gives us a pattern for a bag, tissue box cover or something similar to follow and make up ourselves, or we can choose to do a simple fukin cloth, or use something ready-made. Sewing is my weak point, therefore whenever possible I like to find ready-made items so I can spend more time stitching and less time fussing around with a sewing machine. According to Sensei, sashiko is all about mathematics, and if you can get the pattern right on paper first, you can apply it to anything. I’ve found that drawing patterns onto graph paper over and over really gives insight into how they are formed, which makes it easier to create variations, or adjust the proportions.

While working on drawing up patterns during the lesson we show each other the pieces we’ve made up since the previous month, look at examples of Sensei’s own work that she brings in for us to see, and exchange information about sashiko topics in general. At the end of the two-hour lesson, we finish up with a cup of tea and something sweet (always a delicious treat) and chat for a while. Once a year our group exhibits in a local art exhibition, and last year we also held a solo group exhibition for the first time. Sensei herself studied under the now deceased Eiko Yoshida, a major influence in modern sashiko and author of many books whom I’ll write about in another post. Eiko Sensei’s students and followers are now led by her inheritor, Kumiko Yoshida, and in my next post I’ll introduce a recently published book featuring their work. Thank you for all your kind comments so far. I enjoy reading them! |

Watts SashikoI love sashiko. I love its simplicity and complexity, I love looking at it, doing it, reading about it, and talking about it. Archives

September 2022

Categories

All

Sign up for the newsletter:

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed