|

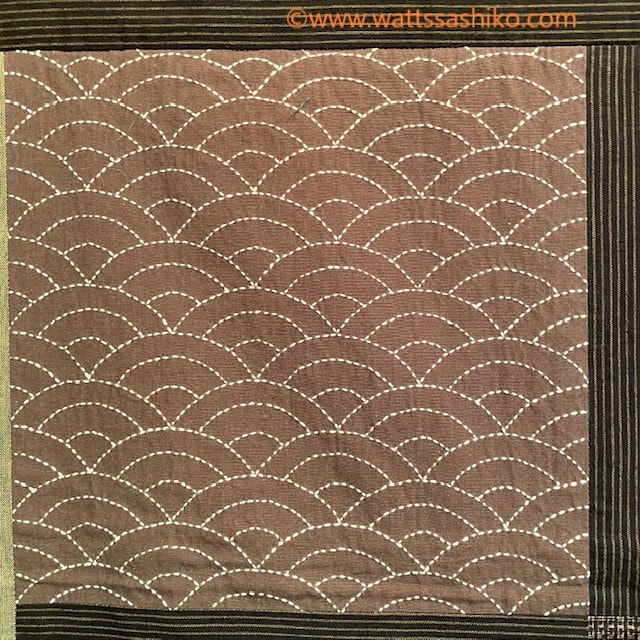

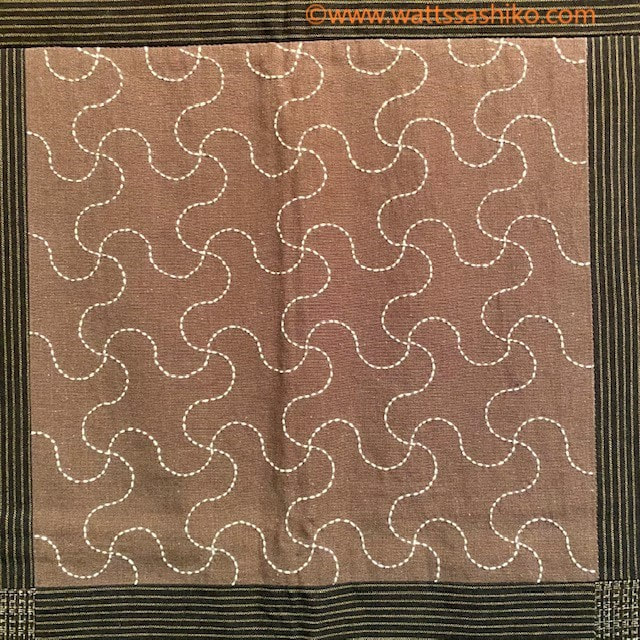

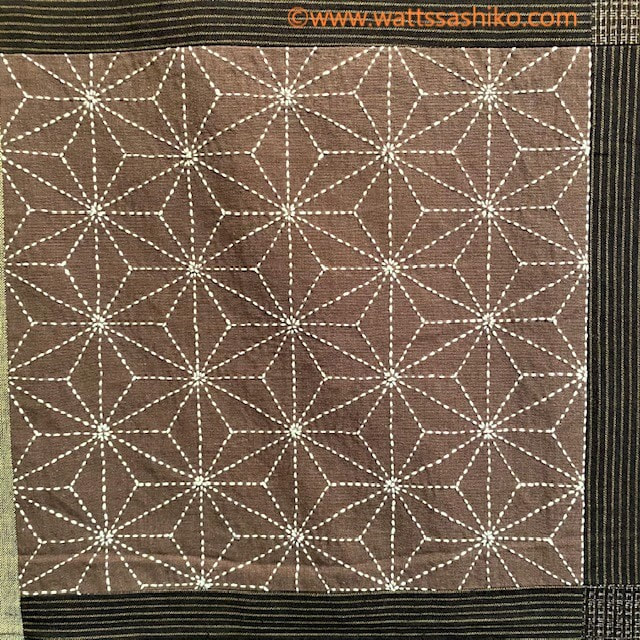

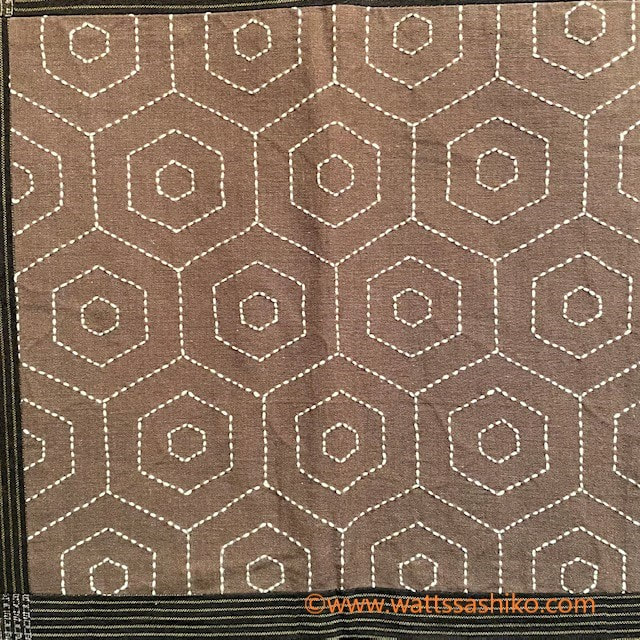

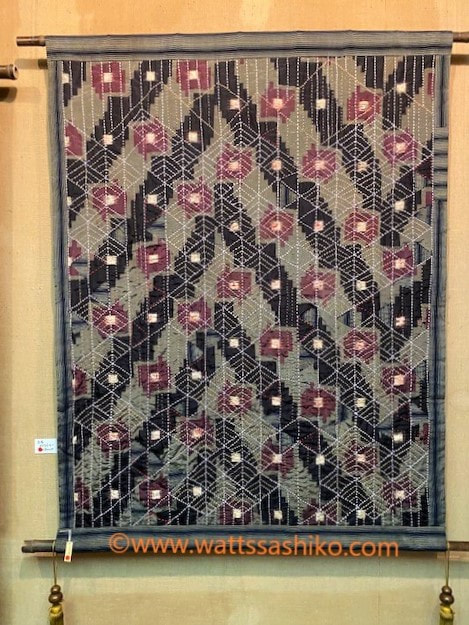

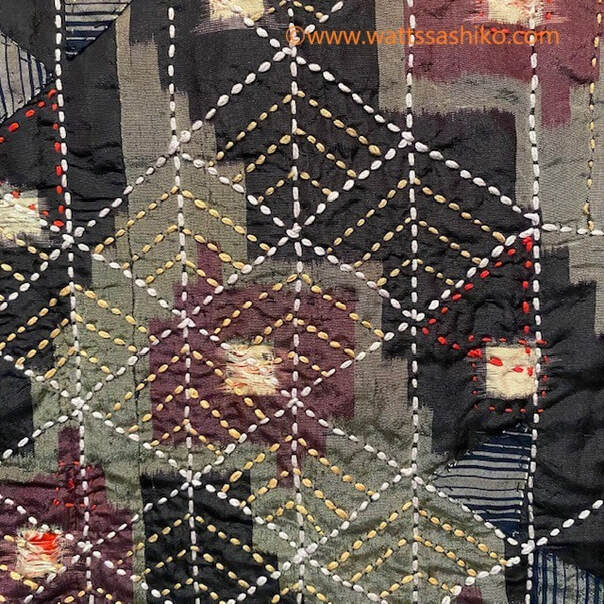

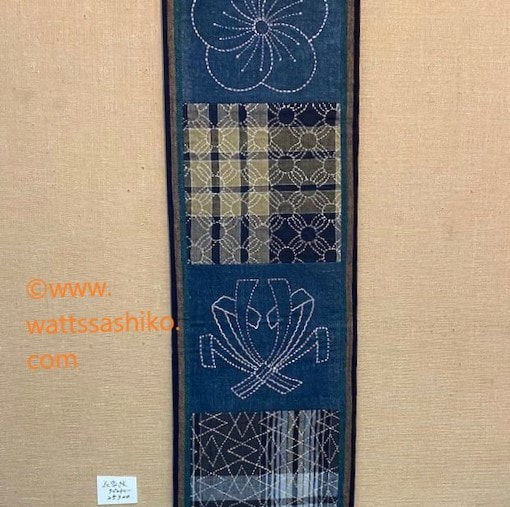

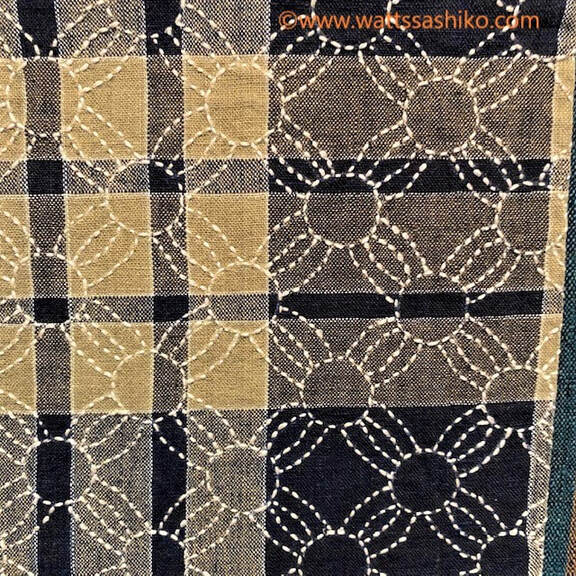

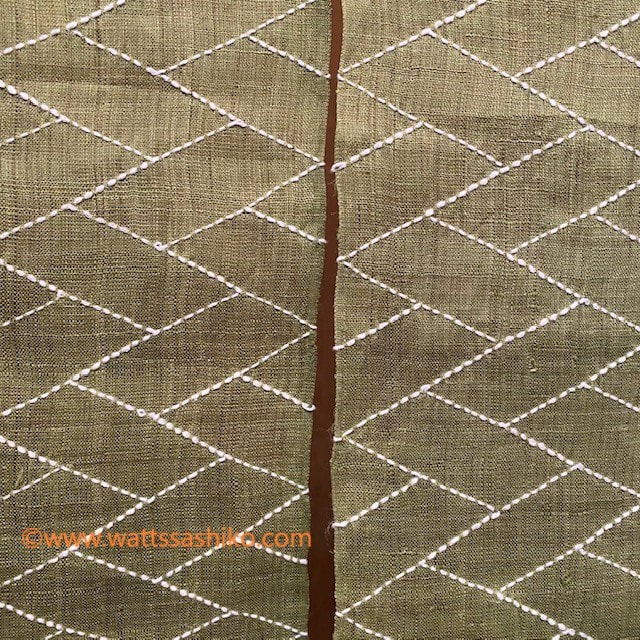

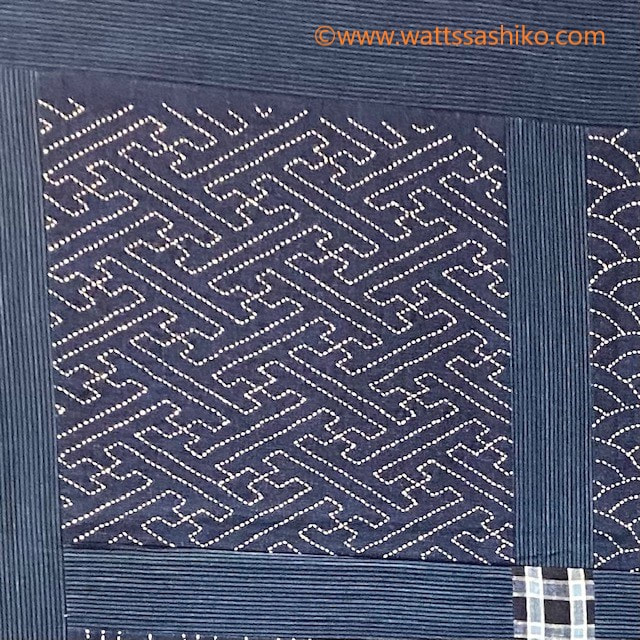

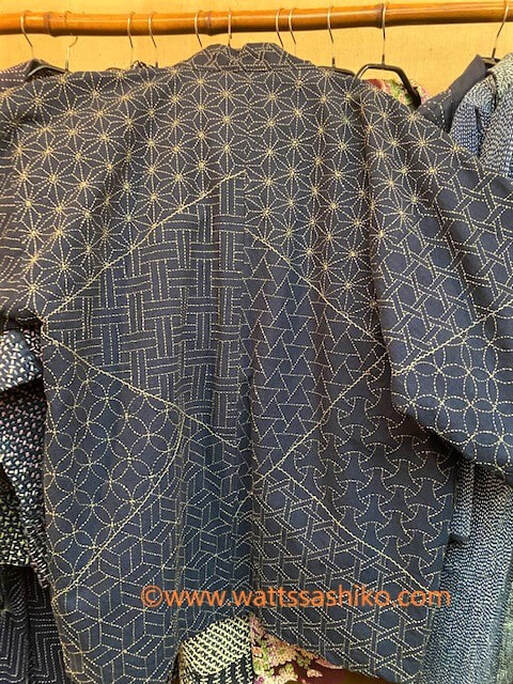

The pandemic has made it hard for many businesses, and sashiko is no exception. When I went to see the travelling Hida Sashiko exhibition recently, I heard that the Takayama-based Hida Sashiko company, too, was struggling. With domestic travel limited, not to mention the states of emergency, business hours are shortened and there is not enough work for staff. Travelling exhibitions like this are an important method of selling their range of sashiko clothing, hangings and bags etc., but the cancellation of many regular dates, such as at department stores, have also hit hard. I’m glad the Yokose Gallery, where I saw the exhibition, was open for business as usual. I have written about my visits to this exhibition before. This is where I discovered the Hida Sashiko Notebook, which continues to be a valuable reference source for me. This year, Notebook in hand, I went looking for examples of patterns from it in the exhibition. This wall hanging yielded several to check off the list straight away. Below are close ups of six patterns from the Notebook This hanging made from old fabric is stitched with diamond blue wave (hishi seigaiha), which creates the impression of waters more turbulent than the round blue wave pattern. On another wall hanging I found circular seven treasures (maru shippo). The overlapping point of four circles creates another small circle. Circles represent harmony and this pattern has come to be associated with good fortune. The seven treasures--gold, silver, lapis lazuli, crystal, agate, coral and clams--comes from Buddhism. This entrance curtain is worked with Japanese cypress (higaki) pattern, a geometric stylization of the interleaved cypress panels used on ceilings, fencing and wainscotting. This bag incorporates a pattern based on the wooden counting rods (sankuzushi) of a tool once used for Japanese-style calculations and divinations. Another paneled wall hanging netted a few more patterns. Sayagata, which I have seen variously translated as key fret, saya pattern, saya brocade, is based on the a diagonal version of the swastika pattern, and which was often seen on Chinese brocade. Rising steam (tatewaku) is self explanatory I think. Of the 29 patterns in the Hida Notebook, I managed to find twelve, but there were probably more tucked away amongst the many hangings, bags, coats and other items on display. To finish, here are a couple of my favourite pieces. The first is a hanten, a traditional warm jacket with a glorious selection of patterns, and the other is an example of long jacket with a pattern called donza which is based on seaweed and originated on the small fishing island of Tobishima in the Japan Sea. The items in the exhibition are not for sale online, but sashiko kits and supplies are available at the online shop.

4 Comments

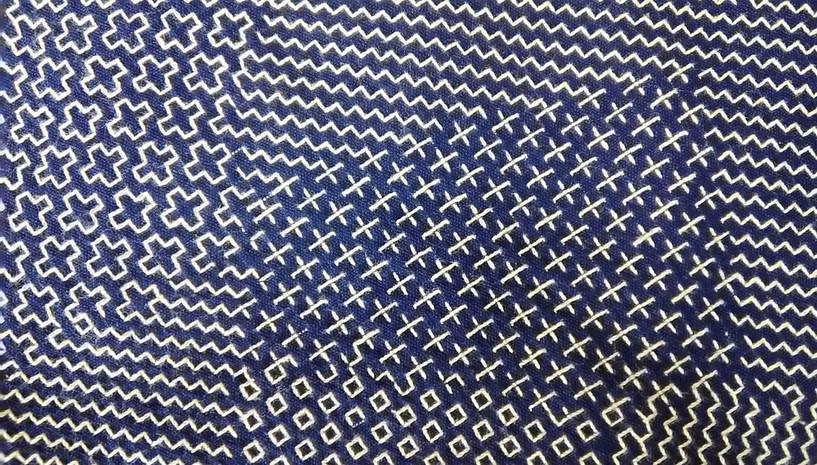

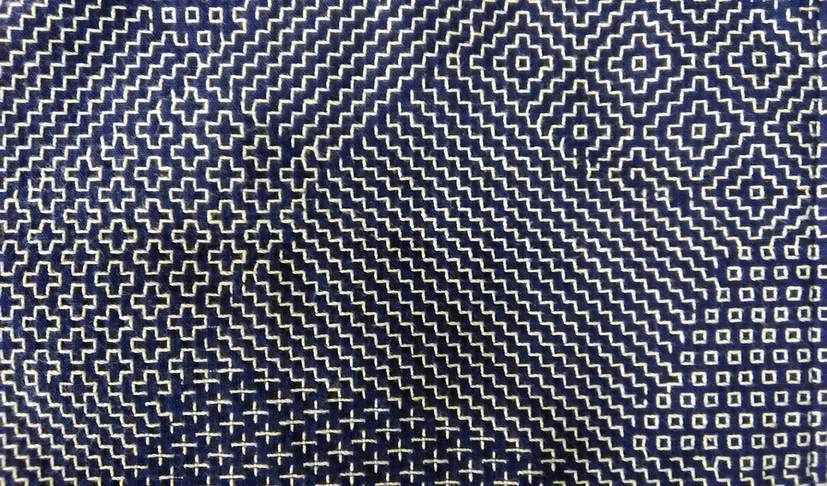

Imagine my delight when the postman delivered me a package recently, and I opened it up to find this gorgeous drawstring bag inside, a gift from an acquaintance who thought I could appreciate it. And she was right! I oohed and aahed with admiration as I examined it every from angle, resisting the temptation to unpick the beautiful red lining and peek at the underside. This type of bag, called a kinchaku in Japanese, was—and still is--used to carry around valuables or personal effects. Although an accessory for Japanese-style clothing, and probably not as common as it once used to be now that Western dress is the norm, it is nevertheless, far from having fallen out of use. I often see the elderly ladies in my neighborhood out for a daily walk clutching their kinchaku. And schoolchildren keep stationery, or implements for school lunches in these bags, though they are far more likely to be decorated with cute characters than sashiko. At summer festivals kinchaku are a common accessory for traditional festival wear, in fact I have a fancy red one to go with my yukata (cotton summer kimono). Naturally cloth kinchaku are ideal for sashiko, and the choice of pattern can indicate anything from seasonal themes to protection from evil spirits or wishes for a long life, or simply a something that catches the maker’s fancy! I’m not sure what dictated the maker’s choice of patterns for my new kinchaku, but it is stitched with a selection of five hitomezashi patterns, typical of the Shonai region in Yamagata prefecture. These are: two types of jujizashi (cross stitch), yamagata (mountain form), sanju kakinohanazashi (triple persimmon flower stitch) and kuchizashi (mouth stitch). I love the way the blocks merge without any border between them. And I am awed by the quality of stitching, which is just incredible! Every stitch is so perfectly aligned and neat you would almost think it was done by machine, but of course that is impossible. Owning this bag will certainly be an inspiration to me to up my game. I am almost embarrassed to post the picture of the one and only kinchaku that I’ve ever made. I find it very useful for holding all the thread, needles and tools together for whatever sashiko project I have on the go, but it’s such a handy item I often divert it for other purposes as well, so making more is on my list of items to do. In the meantime I have my lovely new kinchaku, but I don’t want to spoil it with knockabout use so I’m still deciding what to use it for. One thing I know; I will walk a little straighter when I carry this beautiful bag on me.

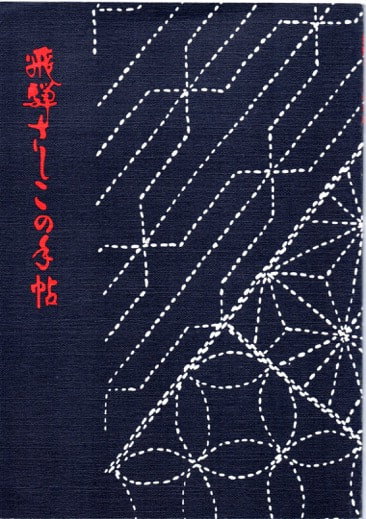

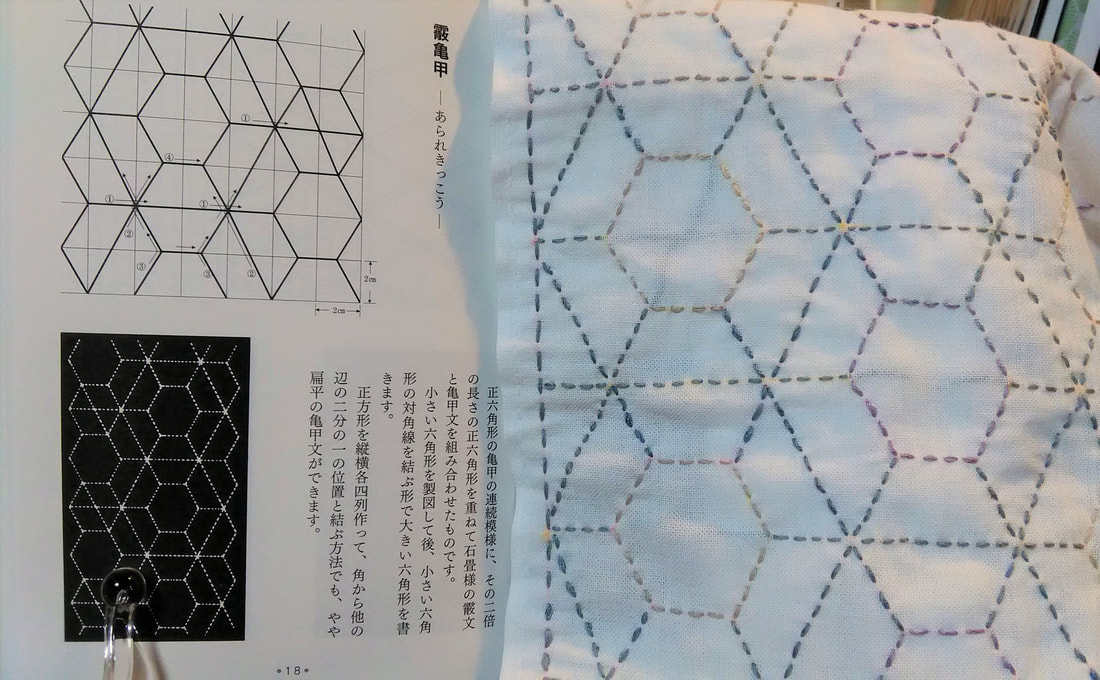

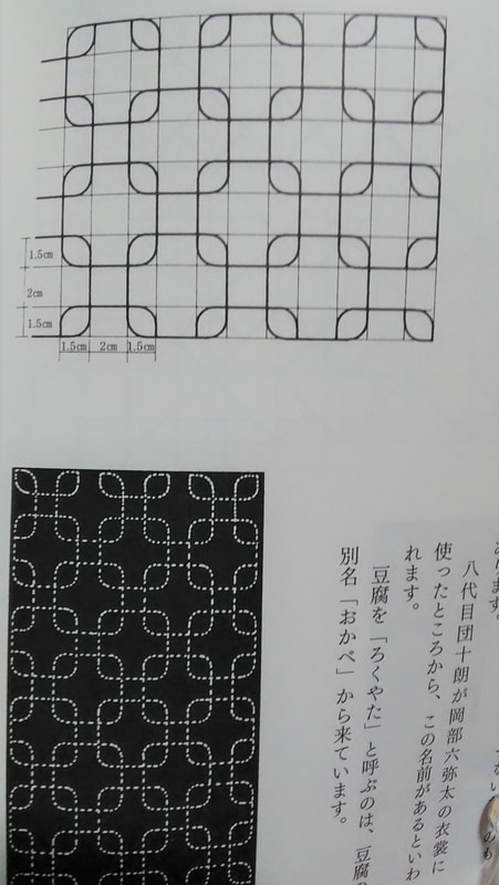

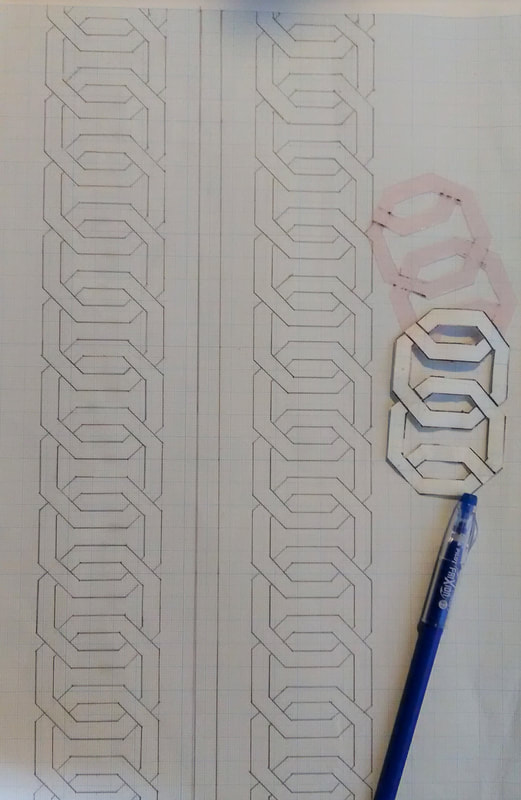

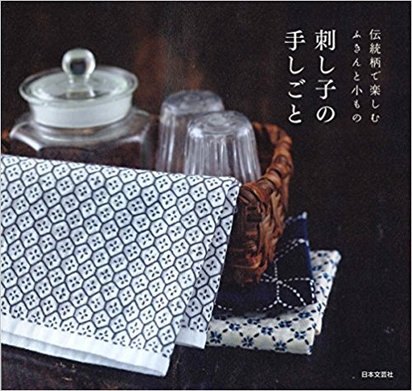

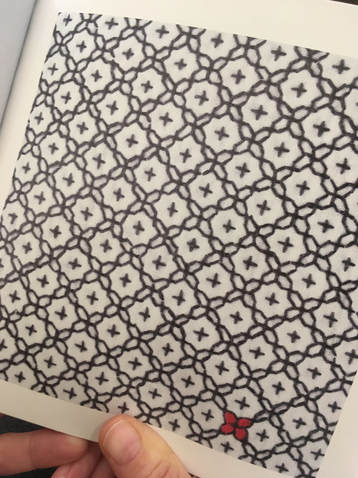

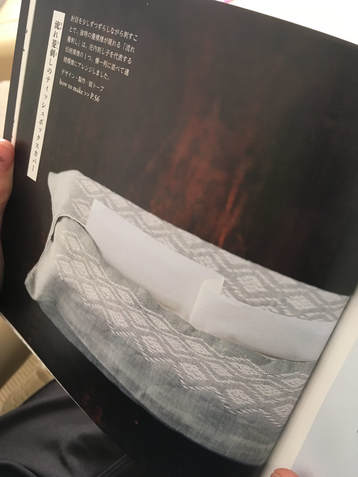

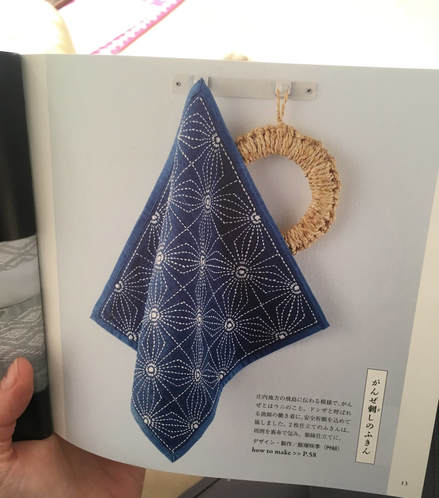

When I visited the Hida Sashiko exhibition last year I purchased a small book called Hida Sashiko no Techo (The Hida Sashiko Notebook, by Reiko Futatuya, first released in 1978, reprinted 2013, published by Hida Sashiko), as I always do whenever I come across a book about sashiko that’s not in my collection. Every book has its own appeal, and I never tire of looking through my collection and taking in the variety of sashiko styles and applications. Anyway, by today’s standards this book is very simple; thirty three pages in mostly black and white, and basically just a reference for patterns, but in 1978 when it was first published I doubt there were many books about sashiko available, so I am sure it would have been a valuable resource. (Still is, actually. I found it referred to less than a year ago on this blog, which is written in Japanese, but the photographs are lovely.) As with most such books there is a general description of sashiko’s roots in reusing and reinforcing cloth, but I liked the concrete examples given; for example stitching the tabi (socks) worn by the boatmen transporting lumber down the river to make the sole non-slip in the water; or stitching a chrysanthemum motif in the in the corner of a furoshiki (wrapping cloth) to prevent knots coming undone. There’s a brief discussion of cloth (hemp, cotton and silk), thread and needles, and tools with the general advice of choosing the thread and needles to suit your purpose. All in all there are twenty-eight designs introduced, which the author says are a sample of those most commonly used in Hida, and are a mixture of hitomezashi (one stitch), and moyozashi (pattern sashiko). Each design has a simple explanation of the name, composition and roots, and shows the dimensions on graph paper so that the patterns can be reproduced and adapted. Most of the patterns were familiar, as I had seen them before in various forms in other sashiko books, but I did find a couple that were completely new to me. One was Roku Yata goshi (Roku Yata lattice), so-called because it was used on the costume of a popular kabuki actor in the early 19th century when he played the role of a samurai called Roku Yata, and the pattern became hugely fashionable. Another was Yoshiwara tsunagi, (linked Yoshiwara) a series of linked octagons, which I have seen printed on towels and clothing but never as sashiko. According to this book it is often used for actors and dancers stage costumes. Further research led me to discover that it was used on the curtains of teahouses in the red-light Yoshiwara district in Edo, hence the name Yoshiwara. For some reason this design struck a chord in me; I love the suggestion of strength and complexity, in a compact simple line – and felt compelled to make something with it, so I stitched it onto the back of my jeans jacket. When Reiko Futatuya wrote that she hoped these patterns would be used for new fabrics and purposes, I don’t expect she imagined this! I’ve been busy getting the online shop ready and haven’t had much time for writing recently (or doing sashiko!), but here’s a review of a book I wanted to tell you about. Also, if you haven’t already ordered, don’t forget to take a look at the three-kit subscription set I’m taking orders for at the moment in my shop.. Anyway, the latest addition to my collection of sashiko books is this neat little volume published by Nihon Bungeisha in October. Sashiko no Teshigoto (Sashiko Handiwork - Amazon Japan affiliate link) is a collection of beautifully photographed fukin and other small handiwork items — such as a tissue box cover, purse, bag and coasters — with instructions on how to make them. As so often happens, when I bought this book and flicked through I immediately wanted to make everything, which of course I don’t have time for. But even if that’s not possible, I still get a lot of enjoyment from simply looking at photographs of beautiful sashiko stitching, and in that respect this book is very satisfying. It could easily be a coffee table book as the photography is lovely. The sashiko handiwork is displayed on mostly dark wood or light backgrounds, in tasteful minimalist settings with only an iron teapot or cane basket as an accent, and the overall effect is traditional yet modern, an accurate reflection of the sashiko items themselves: conventional but with an elegant, contemporary touch. For example, the white hanafukin with a cross flower stitch in charcoal grey, and one red flower in the corner. Or the chic tissue box cover with nagare hishizashi stitched in white on pale grey cotton. One reason I like this book is that it retains an emphasis on the traditional blue and white combination, while offering an updated version with subtle variations on that theme. As with many sashiko books it follows a standard format of introducing a number of sample pieces (in this case twenty), then providing samplers of the stitches, basic instructions on how to do sashiko (with explanations about cloth, thread, equipment, drafting, stitching and making two easy pieces), and instructions for making up each individual item. The stitches are introduced in four categories; straight line patterns such as tobi asanoha (scattered hemp leaf), curved line patterns such as fundo tsunagi (linked weights), hitomezashi such as kaki no hana (persimmon flower), and Shonai sashiko such as ganzezashi (sea urchin stitch). The last, ganzezashi, is one of my most favourite stitches. It could have something to do with the fact that sea urchin is my favourite sushi topping… but I also love the convergence of concentric lines that scream out to me sashiko! Stitched in white on blue cloth, this hanafukin is totally mesmerizing. Next to making it myself, a photograph is the next best thing.

|

Watts SashikoI love sashiko. I love its simplicity and complexity, I love looking at it, doing it, reading about it, and talking about it. Archives

September 2022

Categories

All

Sign up for the newsletter:

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed