|

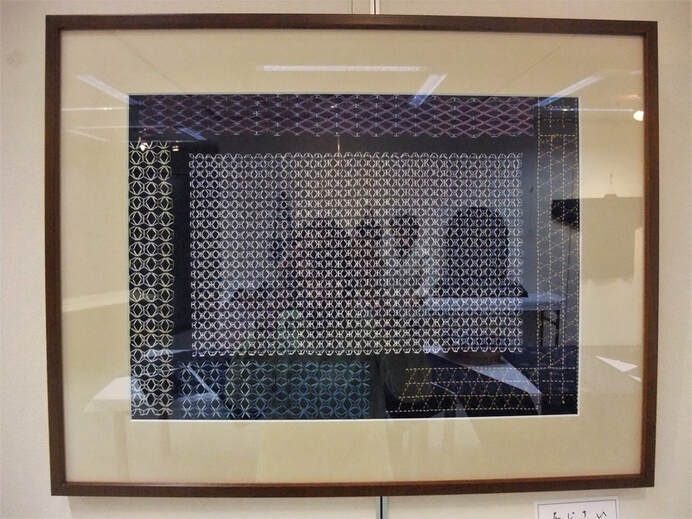

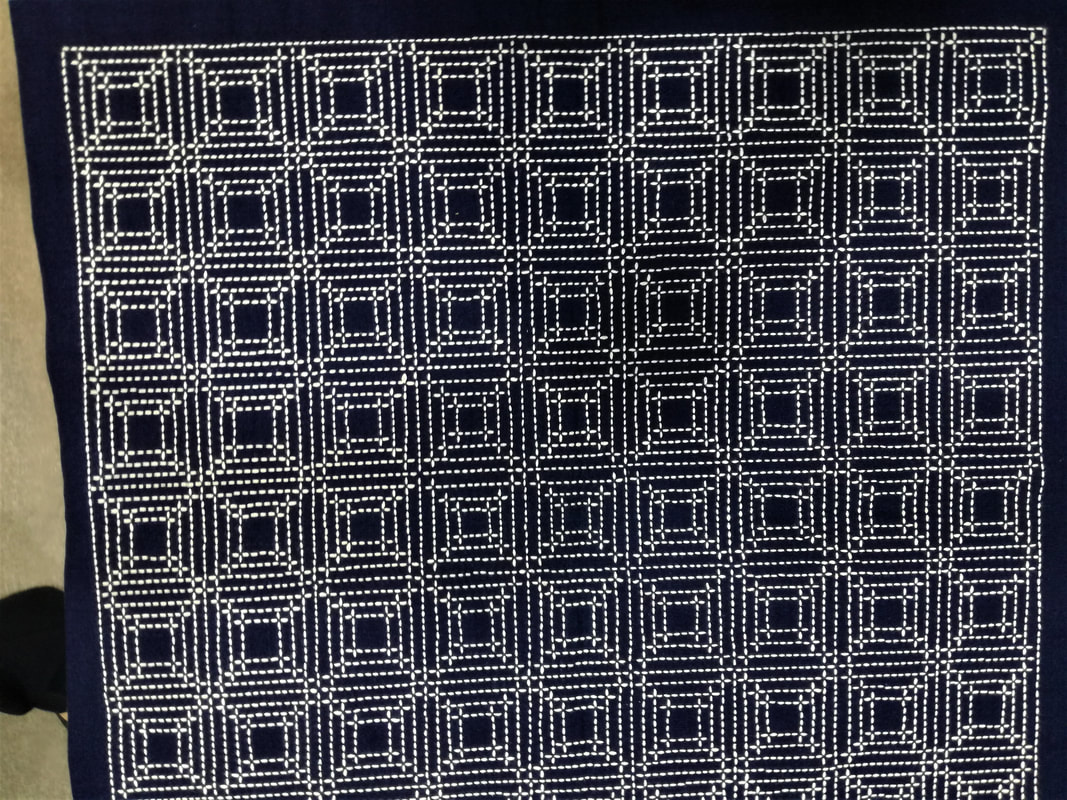

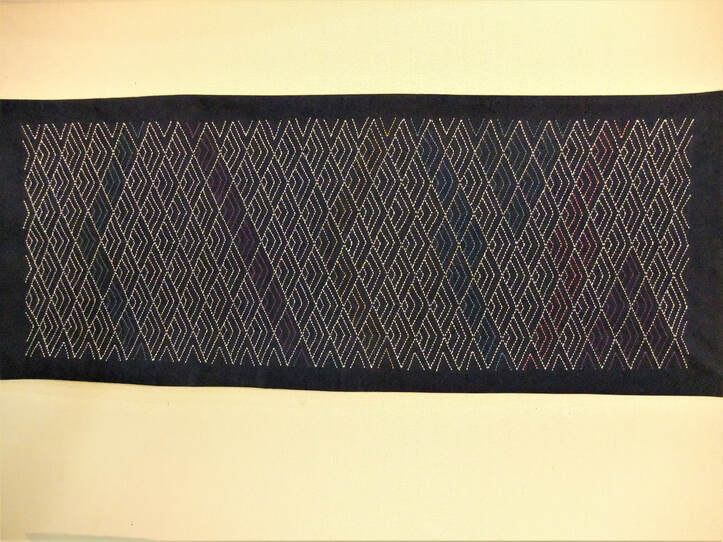

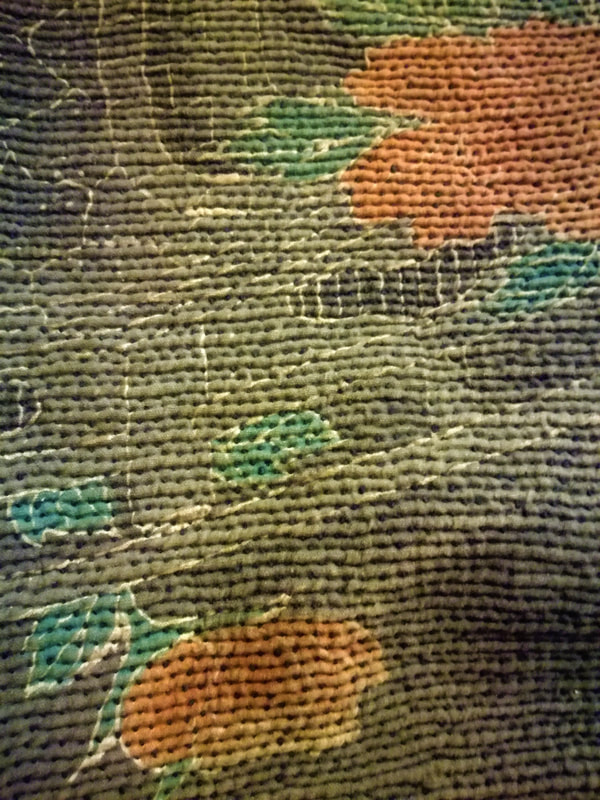

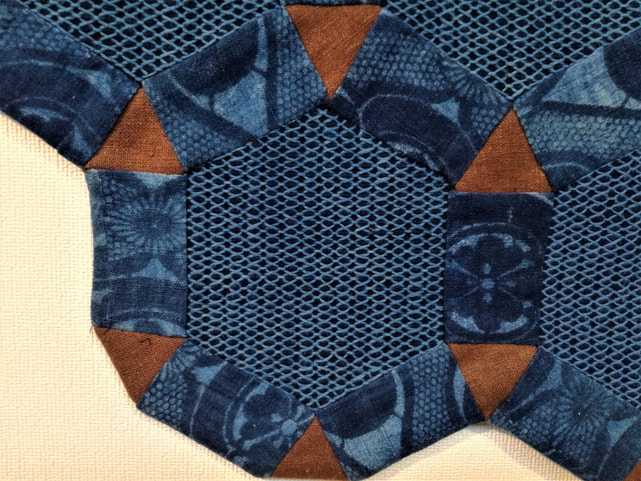

Times are strange indeed when even sashiko class is cancelled because of coronavirus. But if you have to stay at home, what better way to pass the time and stay sane than by doing sashiko. It’s the perfect stressbuster, though I’m sure any sashikoist reading this doesn’t need me to tell you that. This is just another example of how you never know what life will throw up next. After the hiatus of last year I was happy to return to my regular sashiko class in January, but saddened to learn when I did that one of our classmates had recently passed away, at the age of 67. I remember Junko Takashi as quietly elegant, reserved but warm, and always simply and beautifully dressed. She often brought along clothes to show us that she had decorated with a touch of sashiko. In fact I think that was her forte. She confided in me once that she wasn’t much good at sewing—something we both had in common--and enjoyed looking for items of clothing to buy off the rack, that she could individualize with sashiko. I have seen many examples of how she did this on blouses, tunics and jackets. I wish I’d taken photos of them all. After combing through my photo collection, however, I did find a few samples of Junko’s work, which I put here now in memory of a sashiko friend. This cream tunic blouse has shippo tsunagi (seven treasures) on the right sleeve; vertical lines of free sticthing on the front for balance; and seigaiha (blue sea wave) and masu zashi (square measure) on the shoulder. A white blouse with tobi asanoha (scattered hemp leaf) on the front and a form of linked cross (juuji tsunagi) on the right shoulder Concentric circles in purples and showers of vertical lines below. Lovely. It's a pity the glass reflection blocks a better view, but this framed piece is all variations on ajisai (hydrangea). Masu zashi (square measure stitch). Imagine how much time it took to do this! And this! Hishi seigaiha (diamond blue sea wave). Last but not least, this beautiful kaki no ha (persimmon flower) cushion.

1 Comment

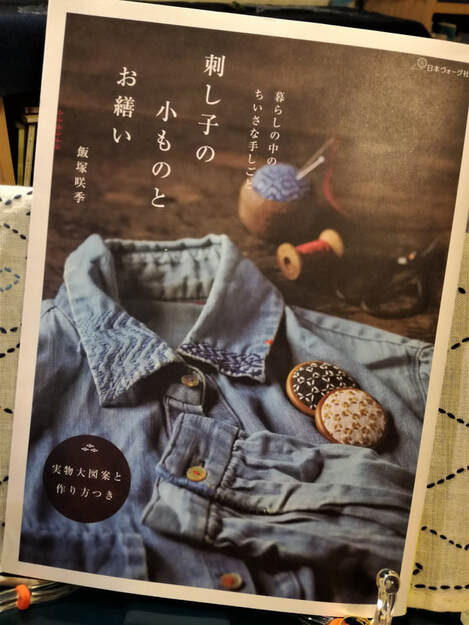

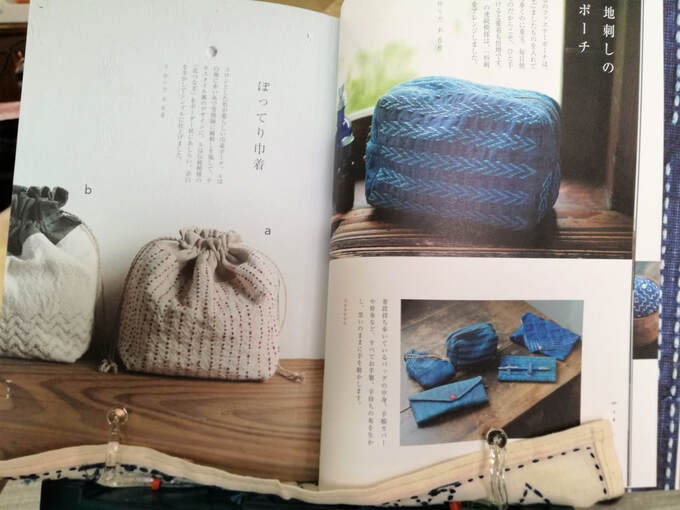

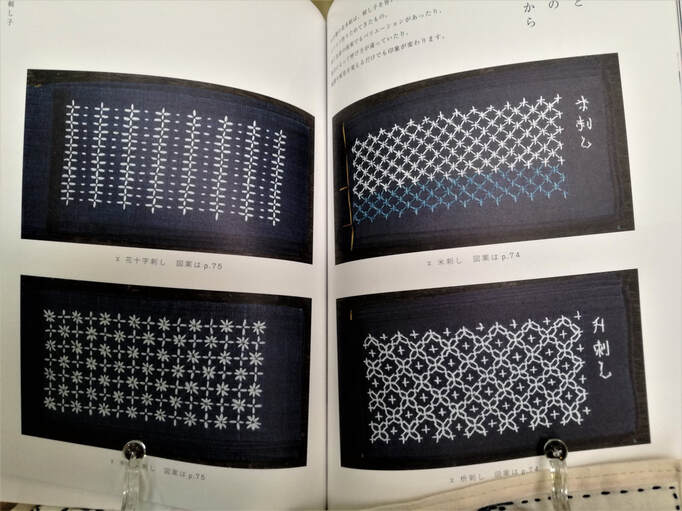

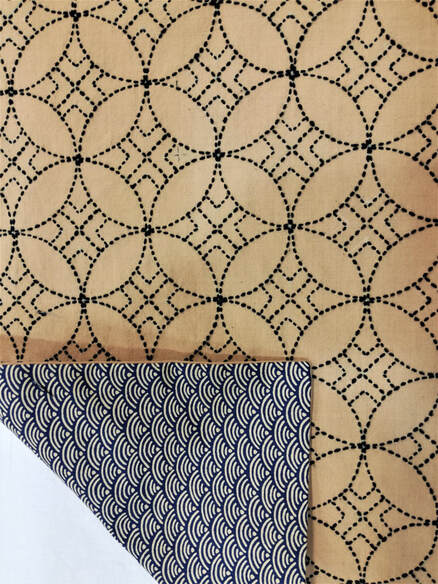

Greetings sashikoists. As it’s been so long since I’ve written a book review, I recently went to check out the shelves in a large Tokyo bookstore to see what’s new. Not much has changed in relation to how disappointedly few books about sashiko in Japanese there are, but I did pick up some new ones. This one jumped out at me as something slightly different. Sashiko no komono to otsukuroi (small items made of sashiko and sashiko mending) by Saki Iiduka was published in November 2019 by Nihon Vogue-sha. It seems to reflect a trend towards focusing on sashiko’s functionality for mending and recycling, rather than simply making pretty handicrafts, as many of the books in the past have. This one is very much a reflection of the author’s lifestyle, and shows how sashiko fits in with her ethos and way of living. Ms Iiduka (pronounced ee-zu-ka) studied painting at university and spent ten years living in the rural prefecture of Yamagata, where she had opportunity through her studies to closely observe rural life. She first encountered sashiko after graduation when she and a group of friends ran a café and lifestyle workshops in an old school building. She began making items for everyday use from sashiko, using and recycling whatever materials were at hand. In this sense her sashiko is close to the origins of sashiko, as a means of strengthening and reusing precious fabric. Many of the items pictured are things that she has made and uses. Nowadays she lives in a village in Gunma prefecture with her family and has a studio called Kaeru-top where she runs sashiko workshops, sells sashiko and runs a café. The first section of the book introduces 21 different items with instructions for making each at the back, and the stitch pattern diagrams shown to actual scale, which is a plus. The items include an amulet bag, brooch, pincushion, coaster, name card case, purse, book cover, pot holder, shoulder-bag purse, box-shaped pouch, sturdy drawstring bag, tote bag, lunch wrapper, stole, and boro drawstring bag. The section on the basics of sashiko has a series of photographs that show the process for drafting and stitching three different patterns (hishizashi diamond stitch, komezashi rice stitch, and hon-juji-hishikake real cross diamond woven stitch) in very clear detail, with the reverse side shown as well. Then there is a section on mending, once again with close up photographs showing how to mend holes, and photographs of suggested items to use mending techniques on, such as shirt collars and cuffs, cushions and knitted socks. My favourite section shows the author’s handmade swatches of stitch samples that she has made over the years for her own reference. I was pleased she wrote that names for the same pattern and variations are different in different regions, as this is something I always struggle with. Just as I think I’ve learned the name of a pattern I will find it in another book that gives it a different name. Nihon Vogue books are always high quality and this one is no different. What I liked most was that it is a real reflection of the author’s actual lifestyle with an emphasis on practicality, which gives it a pleasing freshness and authenticity.

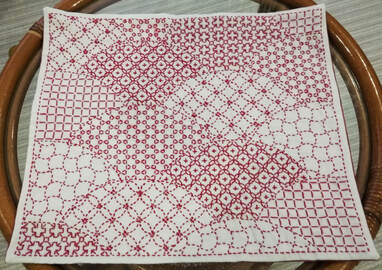

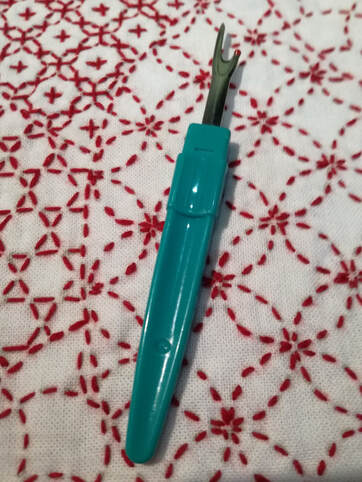

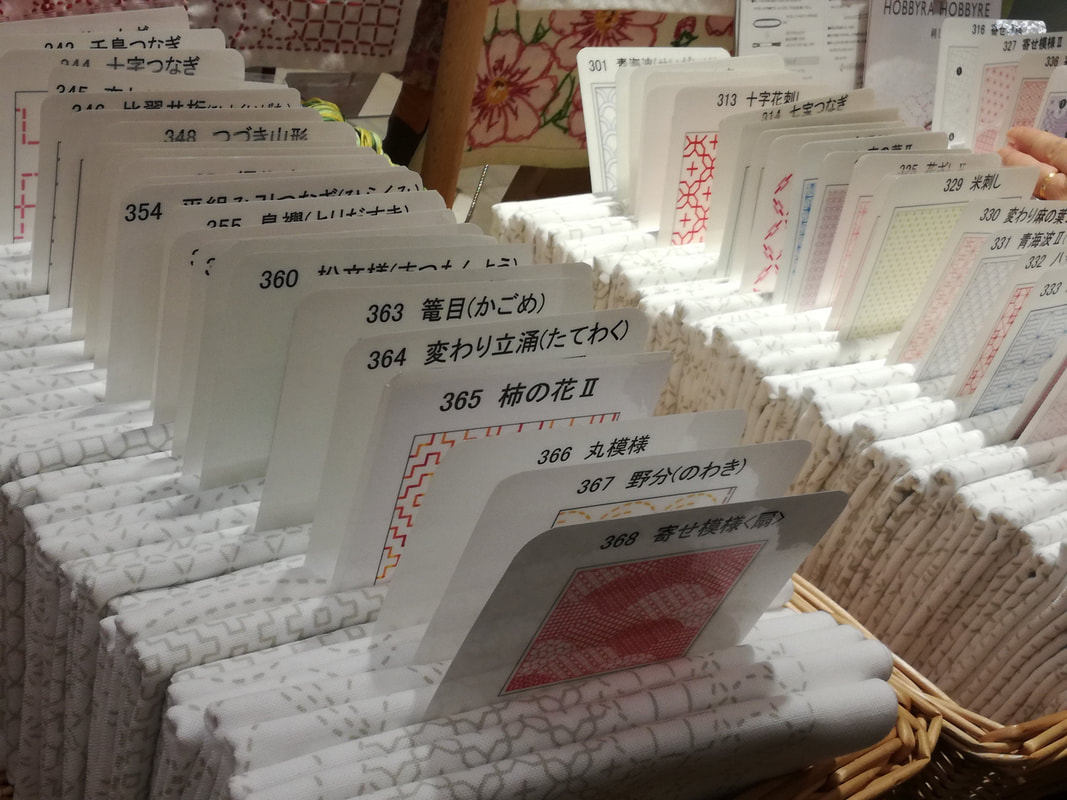

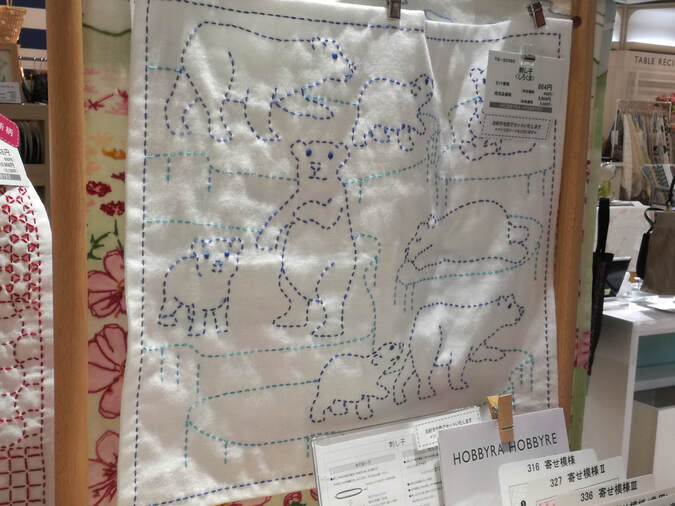

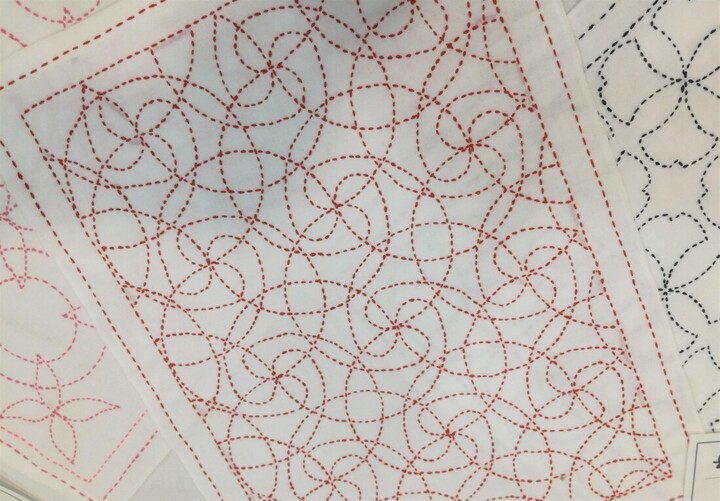

Recently I had the experience of receiving bad news just as I was just about to board a plane. It was an international flight, and after learning that my brother was on his deathbed, I was in no frame of mind for reading, watching movies or any other kind of entertainment over the next ten hours. In that situation all I felt like doing was sashiko. The hypnotizing effect that comes from rhythmically moving a needle through fabric was exactly what I needed to make the long trip bearable. Fortunately I had something to work on. I don’t usually stitch pre-printed pieces as I prefer to draw up my own, but I had with me a Hobbyra Hobbyre brand hanafukin, which I had bought to try out after a visit to one of their outlets in Tokyo earlier in the year. Incidentally, carrying sewing in hand luggage aboard planes can be a hassle because of rules about taking scissors on board. I lost several pairs before discovering that a stitch unpicker is all you need to cut thread and can make it through security inspections without being confiscated. But I make no guarantee - rules may vary according to country! Hobbyra Hobbyre is a craft company that sells mainly needlework and sewing supplies. It was founded in 1975 as an offshoot of the Mitsubishi Pencil Company, with the first store located in the Ginza-Core building in the trendy and prestigious Giza district. From there it expanded into a franchise with 45 shops across the country. Nowadays the Ginza store is located at street level (Denso-kan 1F, 5-9-5, Ginza, Chuo-ku) and has just celebrated its 5th anniversary at these premises. The store I visited was in Shinjuku, on the sixth floor of the Keio Department Store. I was impressed by the extensive range of pre-printed hanafukin with patterns ranging from traditional to free style, and variety of thread colours. There were some really cute and unusual free style designs such as puppies, kiriko glassware and cactus! A range of kits for making items such as bags, purses, coasters and table runners in traditional blue and white was also available. The Hobbyra Hobbyre website doesn’t have any English information unfortunately. This page lists shop locations, which Google translate might be able to help with, otherwise if you are visiting Japan and want to find a shop, try plugging in your destination plus Hobbyra Hobbyre. Below is the hanafukin I began that day in the plane. I like that it had six different traditional patterns and an enclosed instruction leaflet with diagrams clearly showing the order of stitching for each, which were: shippo tsunagi (linked seven treasures), kagome (woven bamboo), hana juji (flower cross) koshi (lattice), juji hanazashi (cross flower stitch) and toridasuki (crossed birds). To finish off I sewed a backing cloth made from an old skirt. The finished piece is indeed full of memories.

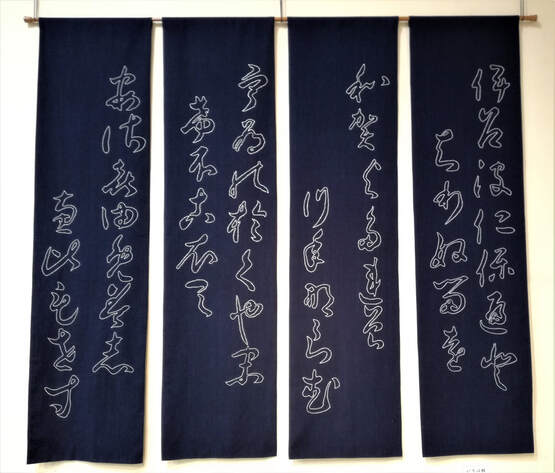

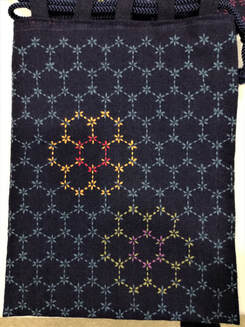

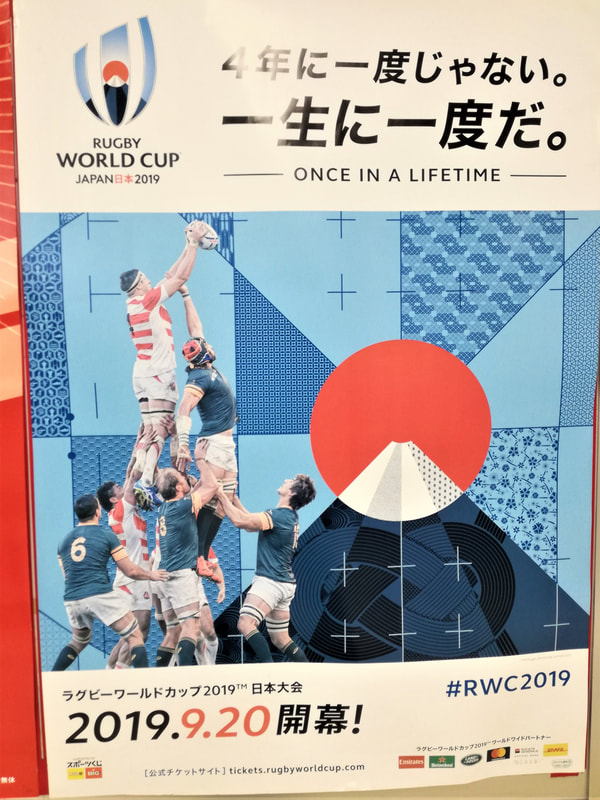

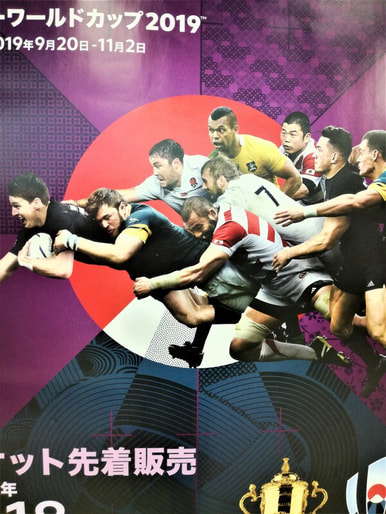

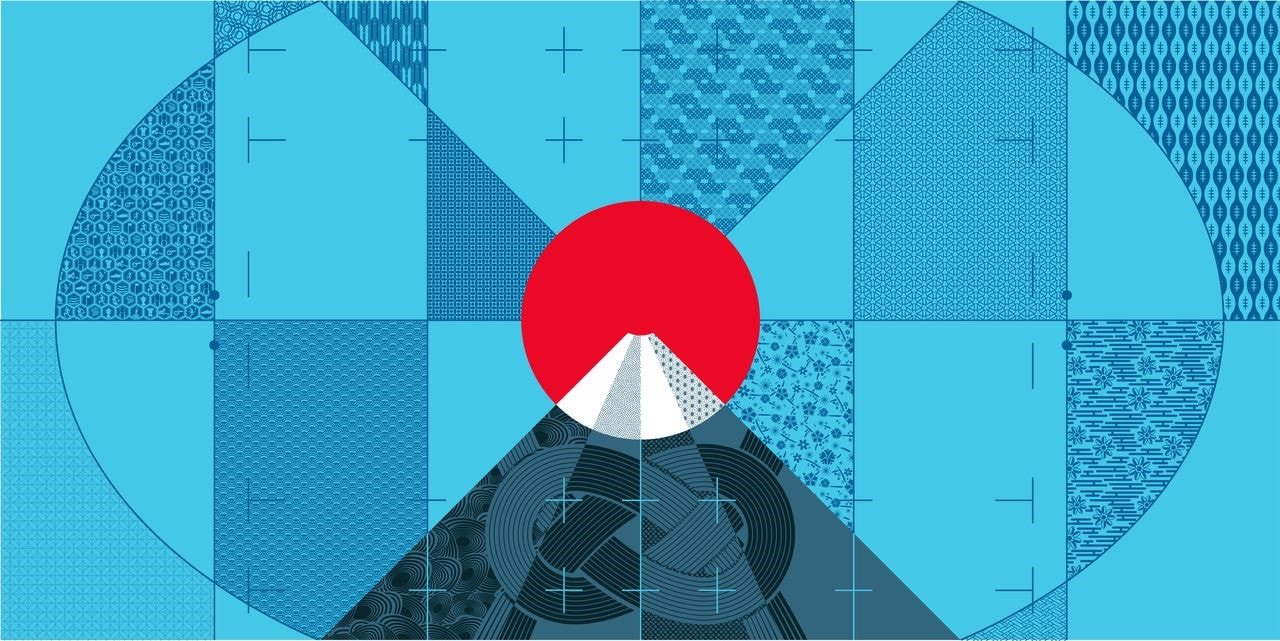

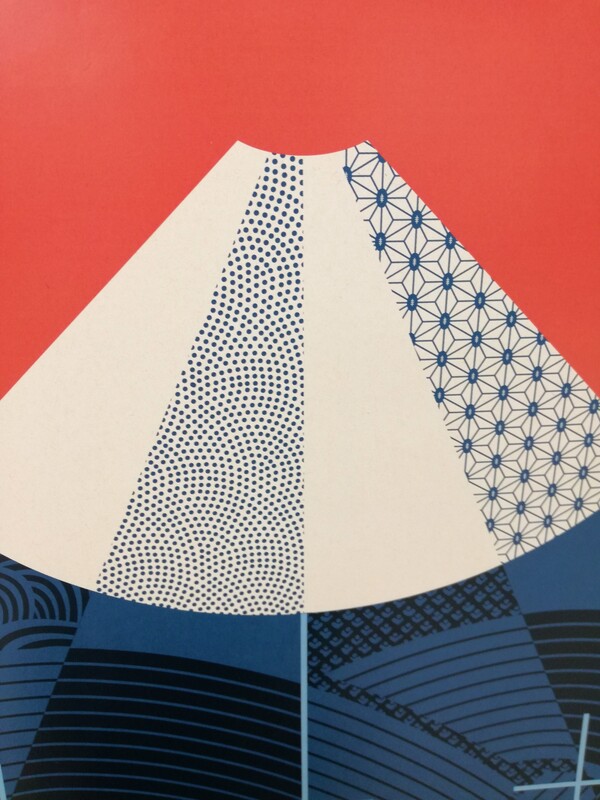

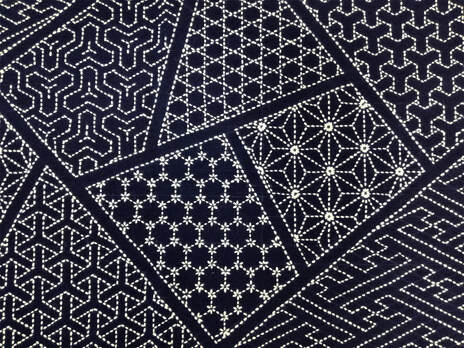

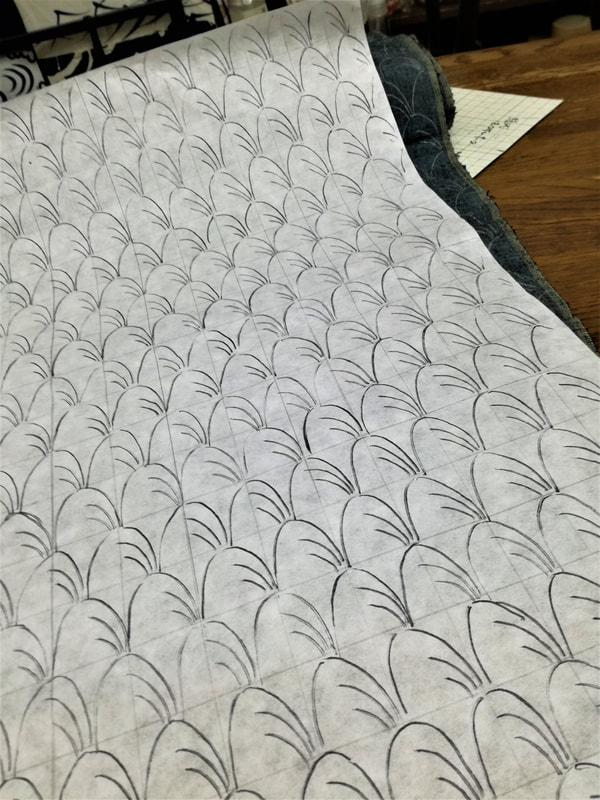

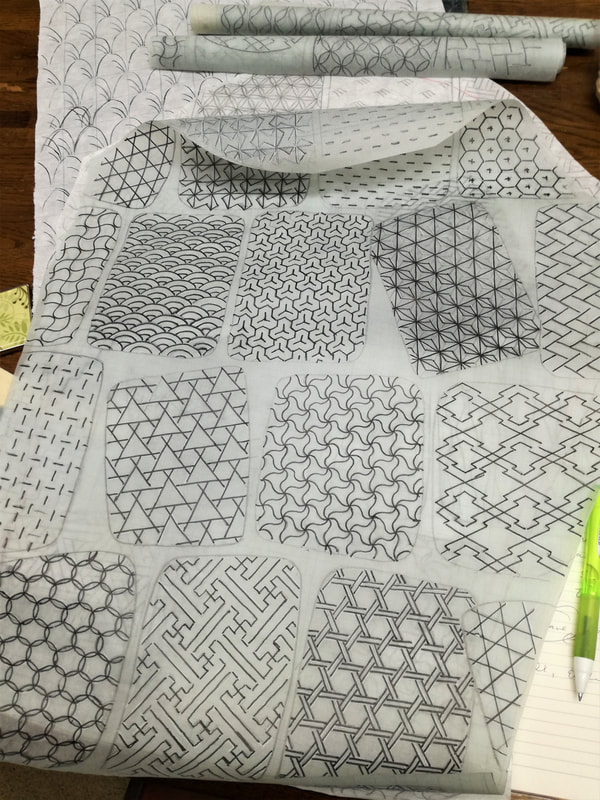

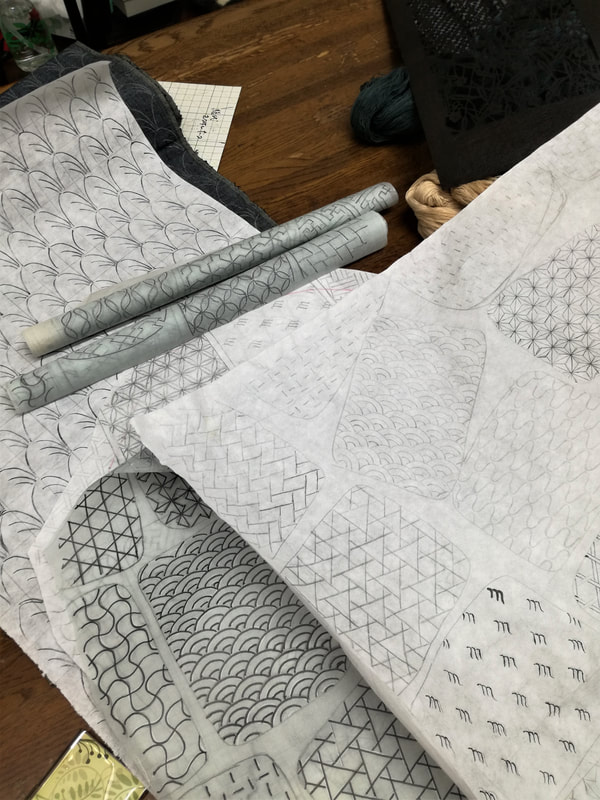

Every autumn, my sashiko group participates in an exhibition at a community art gallery in the train station. Over the last three years I have made a series of framed works featuring different patterns, and contributed to the joint wall hanging that we make especially for this exhibition every year. Although I was unable to contribute this time, I was happy to be able to view the exhibition recently. This years’ joint wall hanging project was a series of four vertical panels depicting the iroha song, an ancient poem famous for incorporating every syllable of the Japanese hiragana syllabary. Sort of like the Japanese equivalent of ‘the quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.’ Even native Japanese speakers can find it difficult to make out what this stylized writing says, so kudos to my four clever classmates who were able to transfer the patterns and fill them out with such beautifully even stitches! Other classmates each stitched flower designs to frame. Here is a selection of a few. The above are all examples of jiyuzashi, or free stitching, which is basically stitching along a freely drawn line. There were also plenty of examples of moyozashi , or pattern stitching. Then there was this spectacular runner below, which was made by one of my classmates done in the bunkatsu (section) style. The patterns you see represented here are (left to right, top to bottom); sayagata (brocade weave), kagome (basket weave), Bishamon (Bishamon-name of a god), asanoha (hemp leaf), tsuno kikko (flower tortoiseshell), and ajiro (wickerwork), plus one more I can’t for the life of me remember or track down – which is driving me nuts! Finally, these three versions of the same stitch, tsuno kikko (horned tortoise shell), on the same kinchaku (drawstring) bag, are a wonderful illustration of how varying the thread colour or pattern size can alter the overall effect. What a thrill it was to see my number one favourite pattern, asanoha (hemp leaf), plastered across the TV screen, splashed around sports stadiums, adorning buses, and even adding a touch of class to rugby balls! Sports matches usually leave me cold, and I couldn’t care less about the outcome of any international match, but my interest in rugby has definitely been raised of late. Rugby World Cup 2019 Japan posters It was all due to the inspired graphic design scheme for the Rugby World Cup 2019, which incorporated a variety of traditional Japanese patterns that were applied to all aspects of the enterprise, from tickets, uniforms and posters to balls, banners and fence advertising and bus decoration, and of course all the mandatory accessories and souvenirs. I was jumping from my seat and getting quite excited every time I got an eyeful of seigaiha (blue wave) on the back of a referee’s shirt as hovered on the edge of squirming bunch of muscly men. Or saw the trunk-like legs of burly rugby players pound a carpet of asanoha at the entrance to the field. I really couldn’t believe what I was seeing. The organizing committee apparently wanted to create an image of unity, and with the image of a traditional screen in mind, they came up with a core design that superimposed the symbols of Japan — Mount Fuji and the rising sun — on a rugby-shaped pitch filled in with traditional patterns. These are the patterns that are at the heart of sashiko. I was already familiar with most, but there were a few I struggled to identify. Watching rugby is way more interesting when you can play “what pattern is that?” at the same time. The Japanese team’s uniform was based was based on an overall concept of a warrior’s helmet, and encompasses a glorious patchwork of the most common traditional patterns any sashikoist would be familiar with: seigaiha (blue ocean waves), kikko (tortoiseshell), asanoha (hemp leaf), tatewaku (rising steam), sayagata (brocade weave), hishi (diamonds) and yabane (arrow feathers). This style of composition is also very typical in sashiko. And oh, by the way, I believe the green team won. Following a tip I’d received about a sashiko shop, I recently went insearch of it in the backstreets of Ueno one rainy afternoon. As I stood outside staring through the window, a straight-backed elderly lady came to the door. “May I come in and look,” I asked. “Well I’m usually closed on Monday but please do,” she graciously replied. It was only when I stepped through the door that I realised this wasn’t a shop at all, it was a workshop. Every available surface surrounding the table in the centre was covered with baskets, drawers and boxes from which scraps of cloth of every size and colour spilled out. “I love fabric,” said Hisaoka-san, for that was her name. In the course of our conversation it became clear she wasn’t just saying this. She meant it from the heart and it shaped the way she lived. With no introductions, explanation, and barely any prompting on my part, she somehow understood I was there to hear about sashiko and immediately launched into telling me all about her ideas and methods. She pointed out a beautiful noren (curtain), made from blue and white panels of fabric taken from discarded shop samples of yukata (cotton summer kimono), and likened what she did with cloth to Spanish architect Antoni Gaudi’s use of broken plates. An irregular shaped sashiko-stitched mat under my teacup had been made from leftover scraps of a suit she had made. Hisaoka-sensei was born and raised in Tokyo. She never learned to sew, sashiko was just something that she had always done since she was a child, to save and reuse cloth. She used the phrase onkochishin many times to describe her philosophy. It means looking to the past and using old things to make something new or inform the future. People like old things, she told me, because they can get a sense of time from them, and time is something you cannot buy. The shop where she holds her sashiko classes is old. Fifteen years ago when her previous premise was knocked down to build condominiums she searched hard for another old building to house the classes she has been teaching for thirty years. In her youth, however, she had done another kind of work, I’m not sure what exactly, but it was related to making designs. That explains to a certain degree perhaps, her unique method of making sashiko designs. She showed me a bolt of cloth she was in the process of hand printing with an elongated nowaki (autumn grass) pattern for her students to stitch. She uses shoji (paper screen door) paper to first draw the design on before transferring it to the cloth. The hand drawn nowaki were evenly spaced overall in the grid, but all slightly different and the overall effect was totally charming. She also hand dyes the thread, as part of her credo of doing everything herself from start to finish. I was astonished when she took me to a corner of the room and started pulling out reams and reams of designs stuffed into a cardboard box. I’ve never seen shoji paper used in this way before but have to say how impressed I am with its strength, flexibility, and durability. I had also never imagined that shoji paper could be used for dressmaking, but Hisaoka-sensei showed me the sheets on which she had drawn the sashiko patterns for a suit she had been commissioned to design and stitch. Apparently it is now being sewn up at a department store. Like most sashiko teachers I’ve met, Hisaoka-sensei said that there are no rules in sashiko. What that means in my experience, however, is there are rules, related to the basic technique of how you hold the needle and method of stitching, and it’s only once you have control over that aspect that you are free. In Hisaoka-sensei’s case, it’s the order of stitching she is particular about. “You need to stitch the pattern in the right order,” she told me. Asanoha (hemp leaf) is one to be particularly careful about. She herself had learned what that right order was from experience. By stitching and unpicking, stitching and unpicking over and over again, she had discovered it. You cannot succeed unless you fail, she said. What this all tells me is that there is an aesthetic that defines sashiko. No matter how easy, free-handed or versatile it is, it is not simply decorative running stitch, and there is a discernable essence that marks a piece of stitching as authentically sashiko. I call it perfect imperfection. Another nugget of wisdom she imparted is that many people can talk about a particular skill, but few can really do it well. To be able to do something well you need to practice it for ten years. By that standard I still have another five years to go with sashiko!

This was a very special encounter. I had arrived unannounced, yet been greeted with gracious hospitality and gifted the gleanings of wisdom earned over a lifetime of experience. We parted with a promise that I would visit again one day—this time with prior notice—to view the store of finished sashiko pieces in the upstairs room. I can’t wait! Sashiko and firefighting would seem to be an unlikely combination, but sashiko has in fact been important to firefighters for centuries. The connection goes back to when the first firefighting squads were formed in 17th century Edo, as Tokyo was called back then. Once Edo became the administrative seat of government under the shogunate it grew from a village into one of the largest cities in the world at the time, full of highly flammable wooden buildings. Widespread destruction caused by frequent fires eventually led to the systematic introduction of firefighting squads. Firefighters required suitably fireproof clothing, and while leather was a suitable material it was not available to all, thus sashiko-reinforced coats and headgear came to be used. Sashiko enabled the fabric to absorb and hold large amounts of water that aided in fireproofing firefighting gear that continued to be used until the early 1950s. In January I saw some marvelous examples of firefighters' outfits at a sashiko exhibition in the Kita-Kamakura Kominka Musuem, all of which come from the museum’s own collection. This was my favourite. A coat from the Meiji era (1868-1912) with a map of the globe as a design. How interesting to see the concept of the earth from this time when Japan was just opening up to the world after a long period of seclusion.  The character in the flag says san, meaning three, which is possibly the number of this group. Firefighting groups were numbered and had their own uniforms. I suspect this flag is what was known as the matoi. The person holding the matoi was supposed to rush to the area try to find a high place to wave the flag so as to attract attention for people in the area to come and assist. This coat dates to sometime between the Edo (1603-1867) to Meiji (1868-1912) era, and has a definite smoke-blackened look! Headgear used sometime in the Edo (1603-1867) to Meiji (1868-1912) era. Here’s another coat dating from the Edo to Meiji period. The swirling black smoke appears to be part of the design. These are some more examples of headgear. This hanten dates from sometime between the Taisho (1912-26) and Showa (1926-89) eras. The characters on the back say Fujieda, which I presume is the name of the city. The frontal characters translate as Fire Squad Member Shingawa-cho (probably a district of Fujieda).

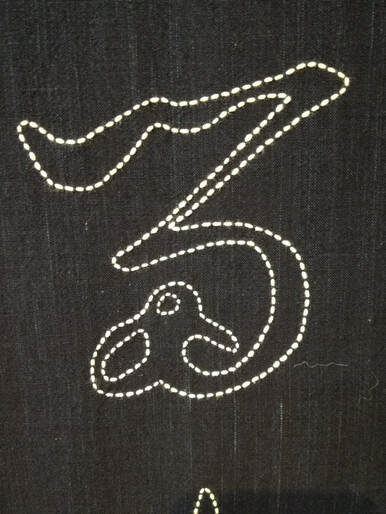

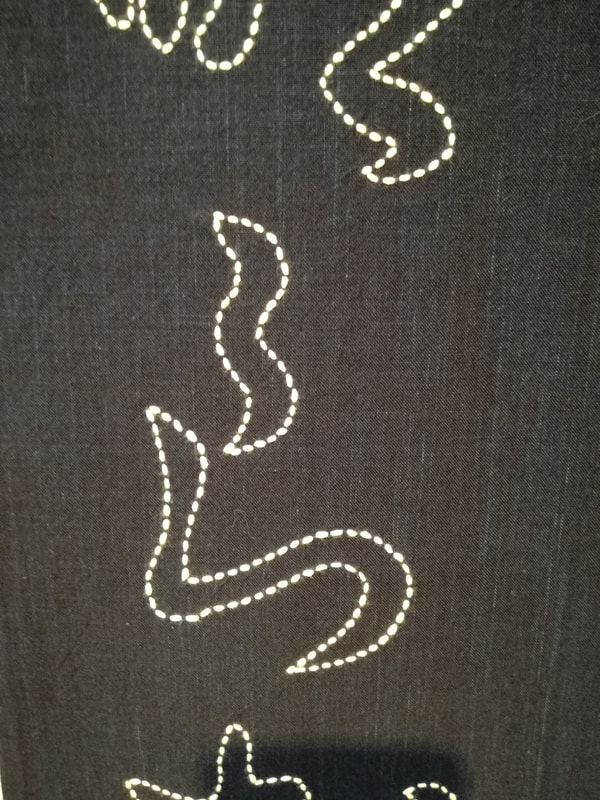

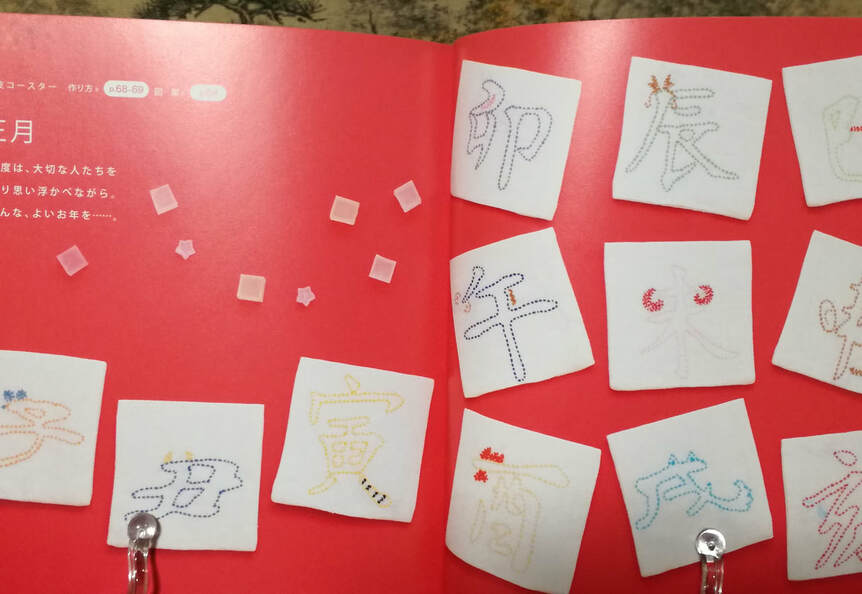

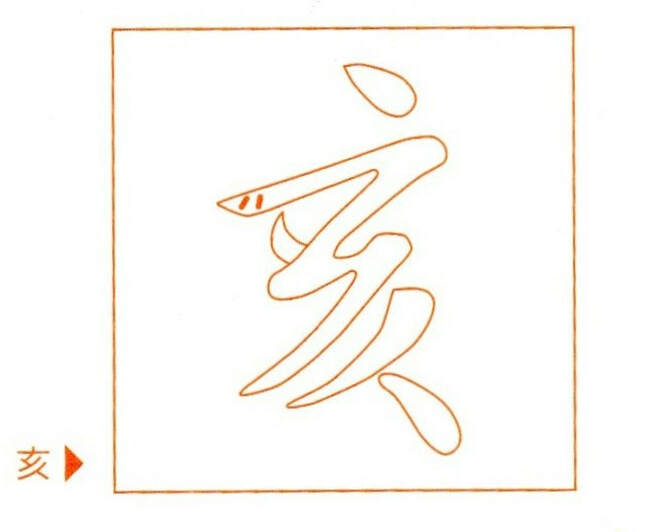

Greetings for 2019 fellow sashikoists! This is just a short post to say hello before January gets away from me. In the Chinese zodiac calendar it is the Year of the Boar, and I am seeing reminders of this everywhere in daily life, on calendars, New Year cards, at the local shrines and temples. People are believed to take on the character of the animal of their birth year, which is supposed to be a special one when it comes around. Boars are said to be sincere, hardworking, have a healthy ego, and make confident and reliable leaders. With two boars in my immediate family, I can say there is some truth in that! In Hideko Onazaki’s book Sashiko no Zakka (Sashiko Everyday Items, Tatsumi Publishing 2010), I found instructions for making coasters stitched with the characters for all twelve zodiac animals. (See more on this book here in one of my earlier posts, Seasonal Inspiration) Below is the character for boar. For those of you already familiar with sashiko techniques, who are able to decipher diagrams and know how to sew up the pieces, why not try making a coaster? An ideal size when completed is 13 cm by 13 cm. Enlarge the design, transfer to the cloth and stitch the sashiko through one layer. Then apply adhesive backing, fold over right side in and sew up the borders (leaving a gap to turn right side out again). Sew up the gap and you’re done. Good luck! I’d be thrilled to hear from anyone who tries it.

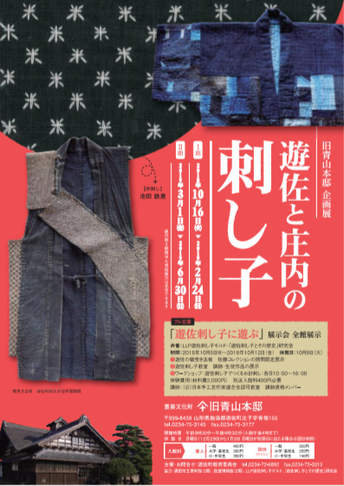

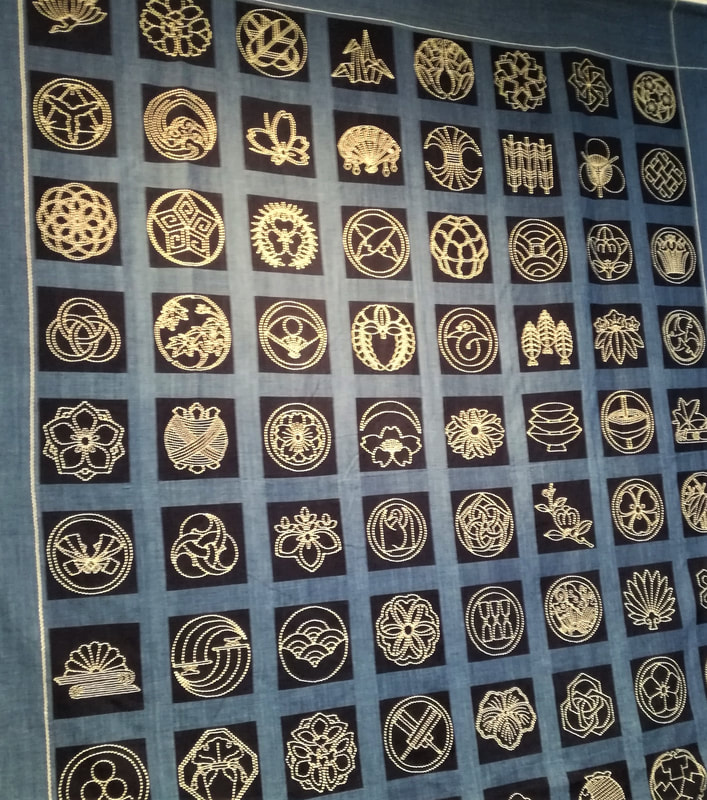

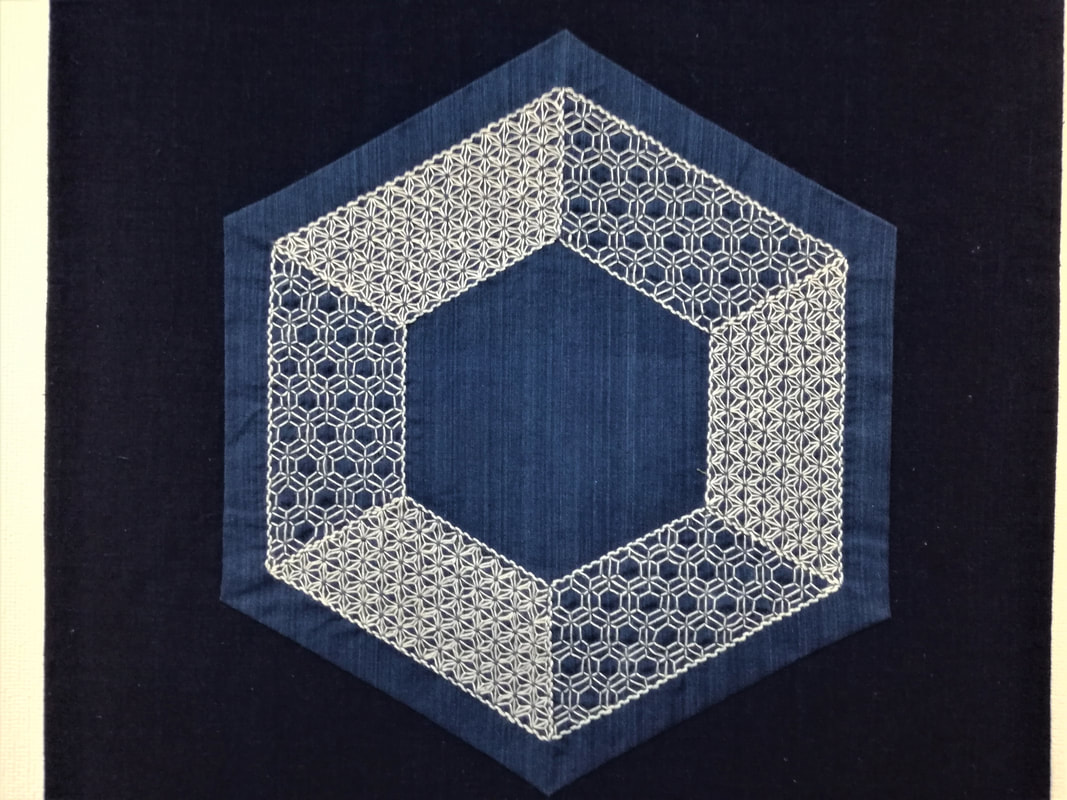

Wishing you all the best in your adventures with sashiko this year. Happy stitching! Alison Autumn is now well and truly here, and in Japan this season is traditionally a time for cultural activities, such as reading and of course sashiko! If you’re in Japan over the next few months, here are a few exhibition dates for the diary. *This post has been updated on 13 November to include the following new event.  Yuza and Shonai Sashiko exhibition, Yuza, Yamagata Yuza and Shonai Sashiko exhibition, Yuza, Yamagata Yuza and Shonai Sashiko Part I Oct 16 2018 ~ Feb 24 2019 Part II Mar 1 2019 ~ Jun 30 2019 9:30-4:30 (closed Monday) Tel. 0234-75-3145 (Aoyama House) Tel. 0234-72-5892 (Inquiries, Yuza Board of Education) Aoyama House Aotsuka 155, Hiko, Yuza-machi, Akumi-gun, 999-8438, Yamagata An exhibition featuring historical garments from Yuza made with sashiko in the Shonai region. Shonai sashiko stands alongside koginzashi and Nanbu hishizashi as one of three major styles of sashiko from Northern Japan.  Genken Arts Club & Friends Exhibition, Tokai-mura, Ibaraki Genken Arts Club & Friends Exhibition, Tokai-mura, Ibaraki Genken Arts Club & Friends Exhibition Sun. Nov. 11 ~ Sat. Nov. 17, 2018 Time: 10:00~19:00 (Finishes 15:00 on the 17th) Tokai Station Gallery, 2F Tokai Station (on the Joban line) Tokai-mura, Ibaraki-ken My sashiko group is participating in this. You can see the joint snowflake pattern wall hangings we’ve been working this year as well as individual pieces.  Sashiko Exhibition, Kita-kamakura, Kanagawa Sashiko Exhibition, Kita-kamakura, Kanagawa Sashiko Exhibition Thurs. Nov. 1 2018 ~ Sun. Jan. 6 2019 (closed Dec. 31 and Jan. 1) Time: 10:00~16:30 Kitakamakura Kominka Museum Yamanouchi 392-1 Kita-kamakura, Kanagawa-ken Tel. 0467 25 5641 This exhibition affords a wonderful opportunity to see the work of artists and groups from Tohoku in different styles and regions, all in the one place. It features the work of Kiyoko Endo (from Yonezawa, Yamagata prefecture), the Nanbu Hishizashi Research Group (Aomori prefecture), Hirata Sashiko Group (Shonai sashiko from Sakata city in Yamagata prefecture) and Hirosaki Kogin Kenkyujo (Hirosaki, Aomori prefecture).  Sashiko and Bandori Exhibition, Sakata, Yamagata Sashiko and Bandori Exhibition, Sakata, Yamagata Sashiko and Bandori Exhibition Aug. 8 ~ Nov. 18 Matusyama Bunka Denshokan, Sakata city, Yamagata prefecture Tel. 0234-62-2632 Website This exhibition features the bandori (a back pad used for carrying things) and other everyday items of sashiko used by fishermen and farmers in the Tohoku region. Work by modern day Shonai sashikoists, Yuichi Onodera and Emi Sato is also on display.  Boro Exhibition, Asakusa, Tokyo Boro Exhibition, Asakusa, Tokyo Boro Currently open until March 31 2019 (closed Mondays) Amuse Museum 2-3-24 Asakusa, Taito-ku Tokyo Tel. 03 5806 1181 Website An exhibition of boro from the collection of Chuzaburo Tanaka. In these humble items of clothing clothing and bedding you can see the origins of sashiko, and how it was used to stitch pieces of cloth together to preserve and reuse. Nanbu Hishizashi Exhibition From Jan 29 to Mar 31 2019 (closed Mondays) Amuse Museum 2-3-24 Asakusa, Taito-ku Tokyo Tel. 03 5806 1181 This is a companion exhibition to the Tsugaru Koginzashi I saw here earlier this year, which was also from the collection of Chuzaburo Tanaka. Nanbu hishizashi, like Tsugaru koginzashi, originated in Aomori prefecture, but whereas Tsugaru koginzashi is blue and white, Nanbu hishizashi is colourful. It seems I am not the first translator to become obsessed with sashiko! The other day I had the great pleasure of viewing an exhibition of work by Hiroko Ogawa and her students from the Mito NHK Bunka Center Class. The eighty-year old Ogawa-sensei has combined her long career as a sashiko artist and teacher with one as a dialogue translator for dubbed films. In fact she has worked on a number of very famous ones, such as “A Streetcar named Desire,” “Rosemary’s Baby,” “Pretty Woman” and “Silence of the Lambs” to name just a few. Ogawa-sensei was born in Kisofukushima-machi, a small town in mountainous Nagano prefecture. She learned sashiko as a child from her grandmother, and many other patterns and techniques from her mother who did Japanese embroidery. However, it was while living in Los Angeles from 1979 to 1989 working as a translator that she began to exhibit her own work and teach sashiko. She has since participated in numerous exhibitions both in the US and Japan, and won an award in the US. After returning to Japan she moved to Nasu in Tochigi prefecture, where she still lives today while exhibiting and teaching classes in Mito and Utsunomiya. Ogawa-sensei’s wall-hanging, below, dominated the exhibition. It is composed of eighty different panels of family crests (kamon), and she made the entire piece herself, stitching all the panels and sewing it together. The reverse side is also beautifully finished. My friend, Katsuko Funada, a student of Ogawa-sensei, made this piece called Mangekyo (kaleidoscope), which is a hall mat, though much too beautiful to step on of course! The overall kikko (tortoiseshell, or hexagon) design is composed of 19 small hexagons stitched with a kikko variation and sewn together quilting style. Another kikko hanging that caught my eye was this Arare kikko to asa no ha (hailstone tortoiseshell and hemp) wall-hanging below, stitched by Toshiko Kato. The densely stitched hemp leaf alternating with the more open spaces of the arare kikko is an eye-arresting combination. One feature of Ogawa-sensei’s work (and even though they are stitched by her students, all the designs in this exhibition are hers) that I noticed is the detail with which they are finished. For example the ends of the rods used to hang the pieces, are coated with sheets of paper used for calligraphy, with poems or songs written on them. Below is a kiku (chyrsanthemum) design wall-hanging stitched by Kazue Yoshida. And finally, geta (clogs) stitched by Mariko Kannai. There were many other exquisite pieces of work, far too many for me to show you here. This exhibition has already finished, but do keep an eye out for the work of Hiroko Ogawa. You won’t find her on a web page, but she does have exhibitions regularly in Tokyo and other parts of Japan.

|

Watts SashikoI love sashiko. I love its simplicity and complexity, I love looking at it, doing it, reading about it, and talking about it. Archives

September 2022

Categories

All

Sign up for the newsletter:

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed