|

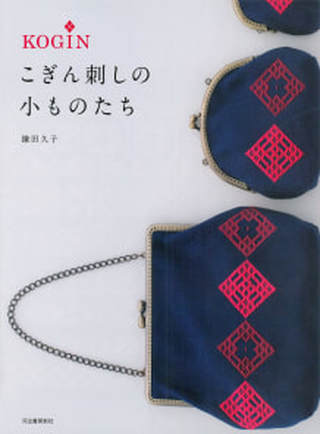

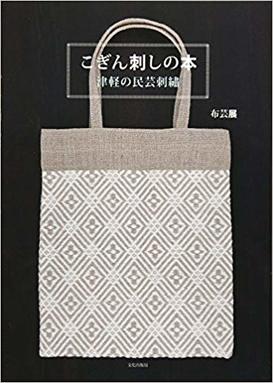

After my recent visit to the Kogin sashiko exhibition in Asakusa, I decided to take a closer look at books about koginsashi. To tell the truth I haven’t paid them close attention before now as I don’t do koginsashi, myself, but my interest was piqued. I started wondering why the type of sashiko that I do and kogin are so radically different. So I turned to my sashiko bible (Sashiko no Kenkyu, Kikue Tokunaga), where I learned that kogin techniques developed as a method of using thick thread to close up the gaps in coarsely woven hemp, the only type of fabric available, whereas sashiko developed from the need to stitch rags together and make layers from them, then stitch over to hold them in place. Hence the kinds of patterns that evolved as a result of these two differences are markedly distinct. Koginsashi patterns are always composed of straight lines because the stitching follows the weave of the fabric, and though there are many patterns they are all uniform. The sashiko patterns that evolved in the Yamagata and Akita area, however, did not have such constraints, patterns have curved lines, and there tended to be more variations and original designs. Here are some of the other books I looked at (with Amazon Japan affiliate links provided):  Tsugaru koginsashi: Giho to zuanshu (Tsugaru Koginzashi; Techniques and Patterns), supervised by the Hirosaki Kogin Research Institute, published by Seibundo Seikosha, 2013 This is a comprehensive book, as you would expect from one supervised by the Hirosaki Kogin Research Institute. It has extensive information on the history, differences between different types of kogin, and clear instruction on the basic method and patterns for reference, including large photo examples. The best part about this book is the beautiful full-page photographs that show close ups of designs and patterns or sections of kimono and everyday work wear. While it’s not the type of book one would go to for craft projects, I feel sure that anyone with a basic knowledge of kogin would get much out of studying the beautiful photographs.  Koginsashi no komonotachi (Small koginsashi items), Hisako Kamata, Kawade Shobo, 2010 The author Hisako Kamata was born in Aomori prefecture, the home of Tsugaru kogin, which is traditionally blue and white, but in this book she introduces a fresh perspective through the use of colour. She shows how to make useful items for daily life such as a cushion, pencil case, coasters, and purses. I was very taken with a cushion in different shades of green. You can see some of the examples by using the “Look Inside” function on the Amazon site. The one review on the Amazon site gives the book high praise and says that basic techniques are explained in detail through photographs that make it suitable for beginners or anyone who is not expert at sewing.  Koginsashi no hon (The Koginsashi Book), Bunka 2009 This book came about as a the result of a collaboration by Yoko Tsukamatsu, who has a tote bag business and Rika Fukuda, a sweets researcher with an interest in folk arts. Together they established the Nunogeiten Project (Fabric art exhibition), and hold exhibitions of fabric items based mainly around koginsashi. Like many books this one introduces basic techniques and several patterns, but what really sets it apart is the stylishness. The bags and purses and buttons that it shows how to make are commonly found in other books, but the ideas for ways to incorporate kogin sashi into clothing, are wonderfully fresh and stylish. I would love a koginsashi patch on the bottom of my pants as shown in here! The book gets rave reviews on Amazon, and I can see why. Finally, one interesting site that I happened across is kogin.net., which has various nuggets of information about courses, books, events, etc. It’s fascinating to see how koginsashi design has been incorporated into modern life in different ways, and on this beautifully laid-out site, even if you cannot read the Japanese the visuals are a feast for the eyes.

4 Comments

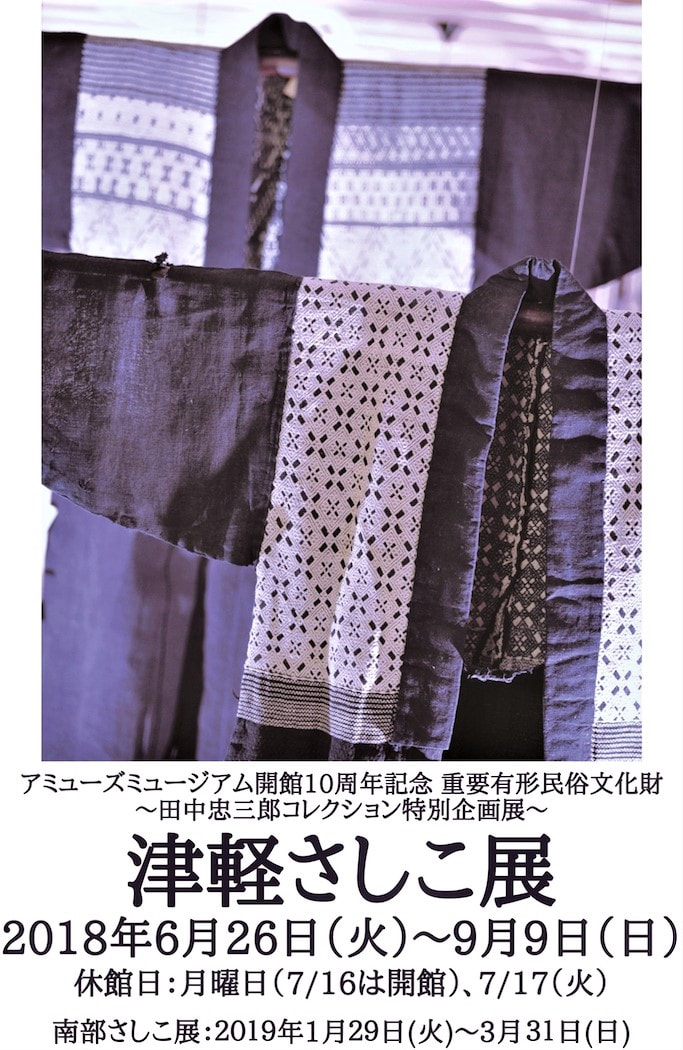

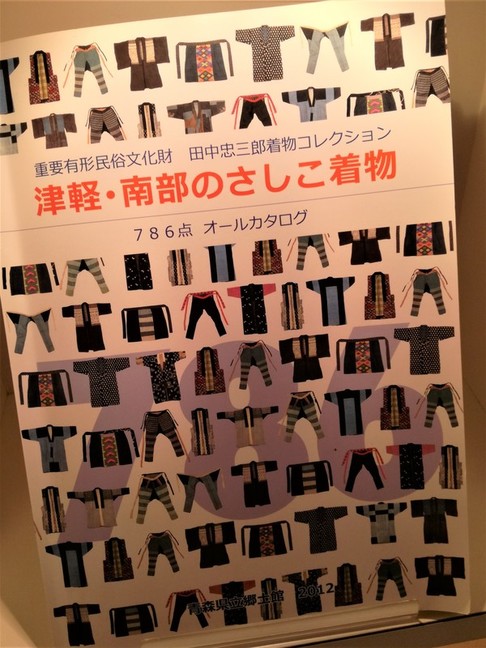

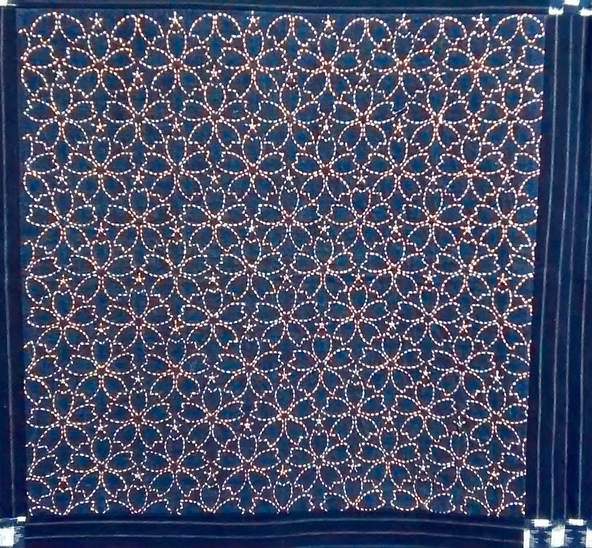

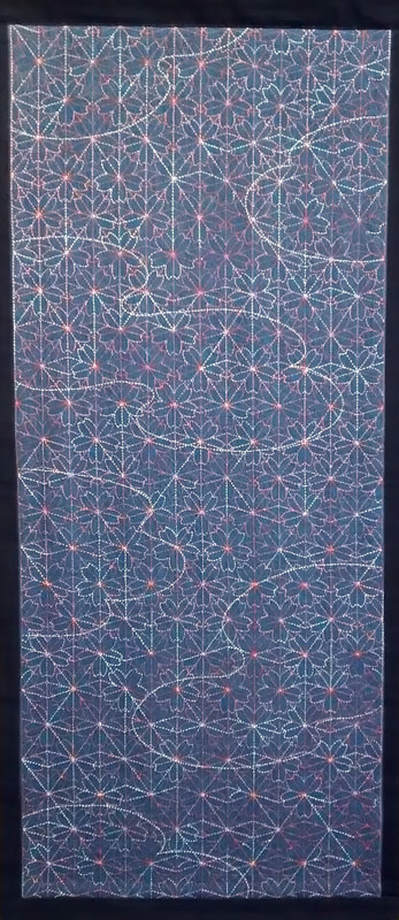

Recently I saw an wonderful exhibition of Tsugaru koginzashi kimono from Aomori prefecture at the Amuse Musuem in Asakusa, Tokyo. This museum is where textiles from the collection of Chuzaburo Tanaka (1933-2013) are housed. Tanaka was a folklorist researcher from Aomori Prefecture, the northernmost prefecture of Japan where the distinctive form of kogin sashiko was born. For close on fifty years he researched the life and customs of ordinary people, visiting villages and remote areas to research and talk to elders, and in the course of this he amassed a huge collection of items that told about life in the past. The collection contains 786 items of sashiko clothing that are designated as Important Tangible Folk Cultural Properties by the Japanese government. Thirty-three of these are currently on display in this exhibition of Tsugaru koginzashi. The climate of Aomori is extremely cold, too cold for growing cotton, which is why the common people grew hemp to weave into fabric for making clothing. Everything in fact, from underwear to babies’ nappies and futons, had to be made from hemp. The Tsugaru and Nanbu clans that ruled Aomori forbade common people from using silk or cotton—expensive items that had to be shipped in from other regions—and what’s more forbade them from using more than one layer of fabric to make their clothes. Hence this technique of densely stitched sashiko was born of the necessity to make what little cloth they had at their disposal, as strong and warm as possible. The major difference between Tsugaru kogin sashiko made in the Tsugaru domain (the Japan Sea coast side) and Nanbu Hishizashi from the Nanbu domain (on the Pacific coast side) is the use of colour. When a railway was extended to the Nanbu area in the late 19th century, coloured thread was brought into the area, and its use permitted by the feudal lord. In the Tsugaru domain, however, the lord was a lot stricter and the use of coloured thread was forbidden. This exhibition displays the blue and white sashiko from the Tsugaru region, but from January 29 next year there will be an exhibition of colorful Nanbu sashiko. This Tsugaru exhibition is open until September 9th. What a contrast these kimono are to our current era of fast clothing! As I walked around looking at each one, I was overcome by the thought of how much time went into making them, and how they were treasured—and still are—for years and even decades after being made. The sleeves on this piece, which was made sometime after WWII, are tapered for ease of movement. This was the only kimono to be stitched with kogin sashiko on the upper part, and hitomezashi (one stitch sashiko) to strengthen the fabric on the lower section. This kimono was worn by a woman from a farming family from Hirosaki. Longer in length than daily working wear, it was made for use on special occasions. The stitching almost looks like lace! These kimono were originally stitched with white thread which was then dyed blue. Tsugaru sashiko apparently has more than 200 geometrical patterns. I haven’t done kogin sashiko myself so I’m not familiar with the names of the patterns, but you can see from these photographs how intricate and varied they are. If you happen to be in Asakusa, Tokyo before September 9th, I do recommend this exhibition!.

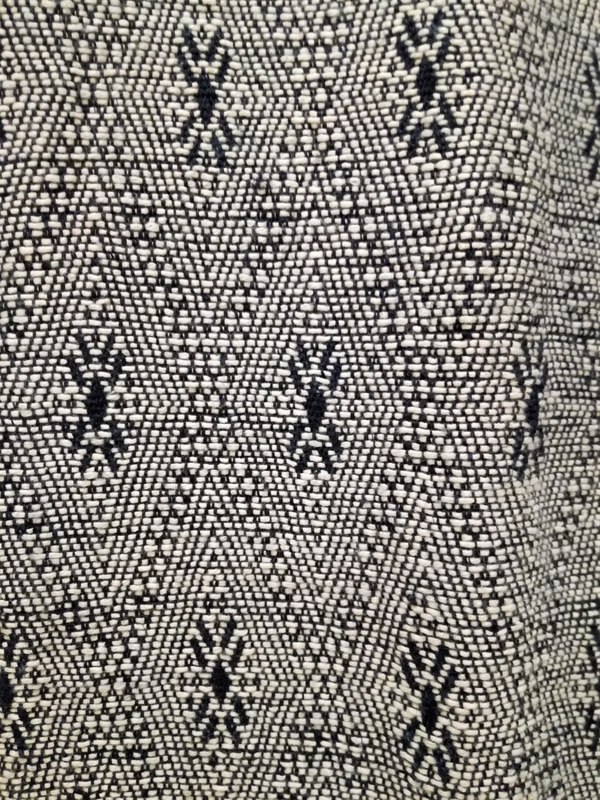

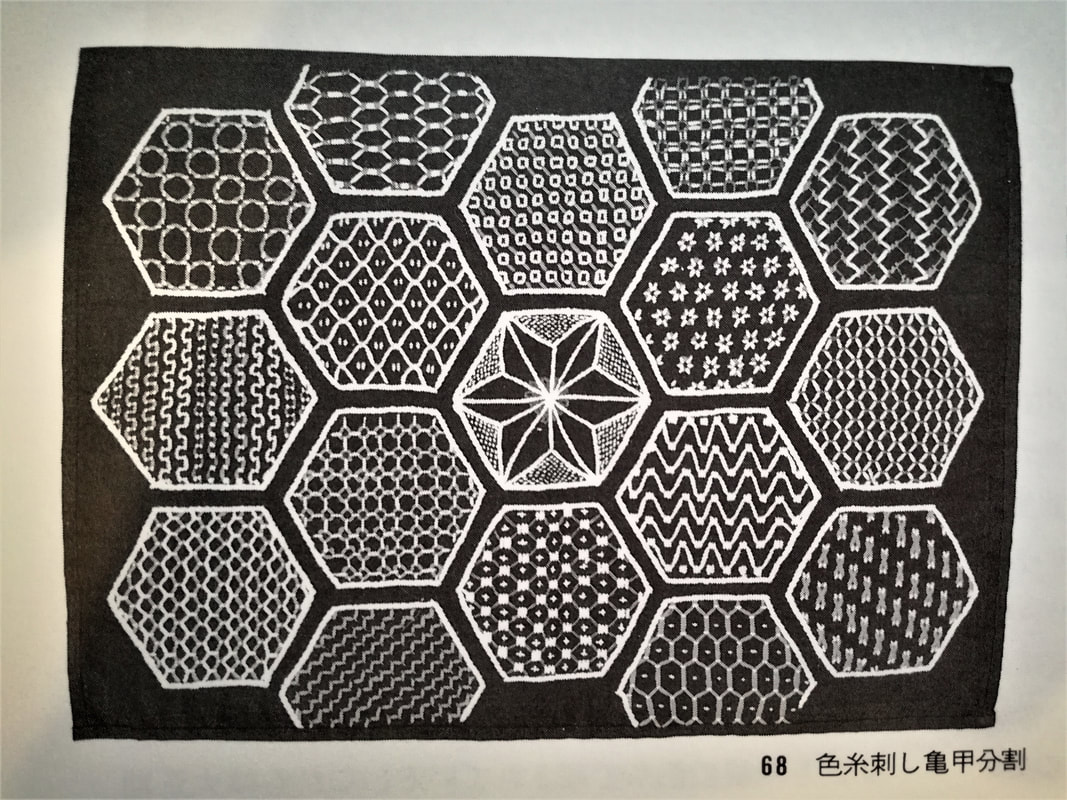

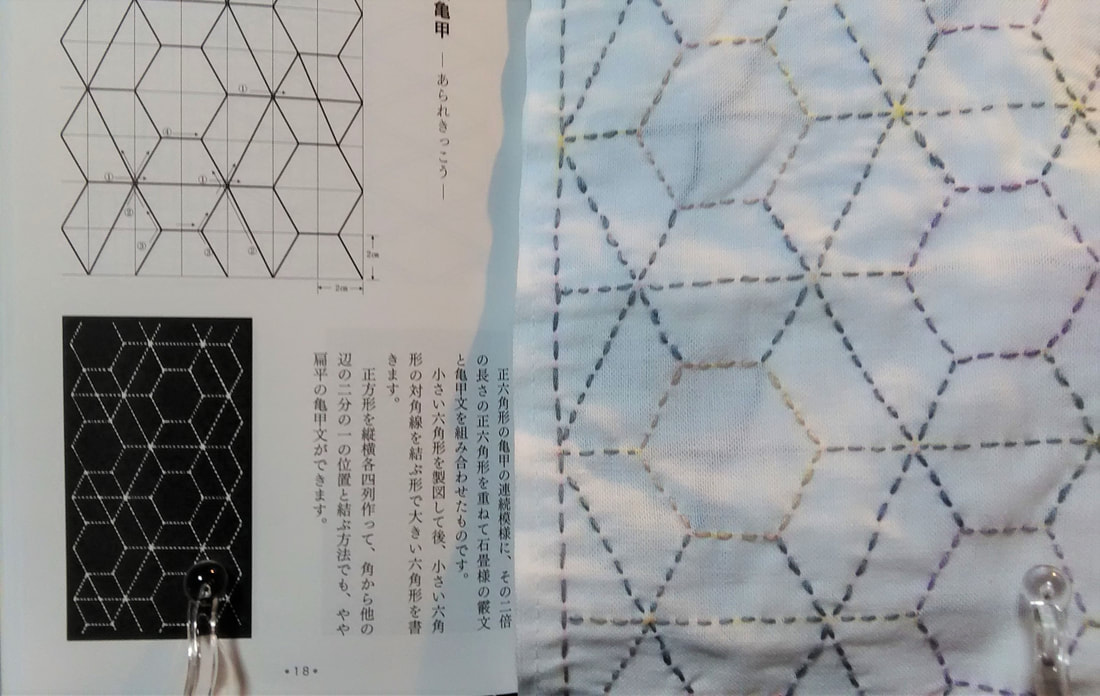

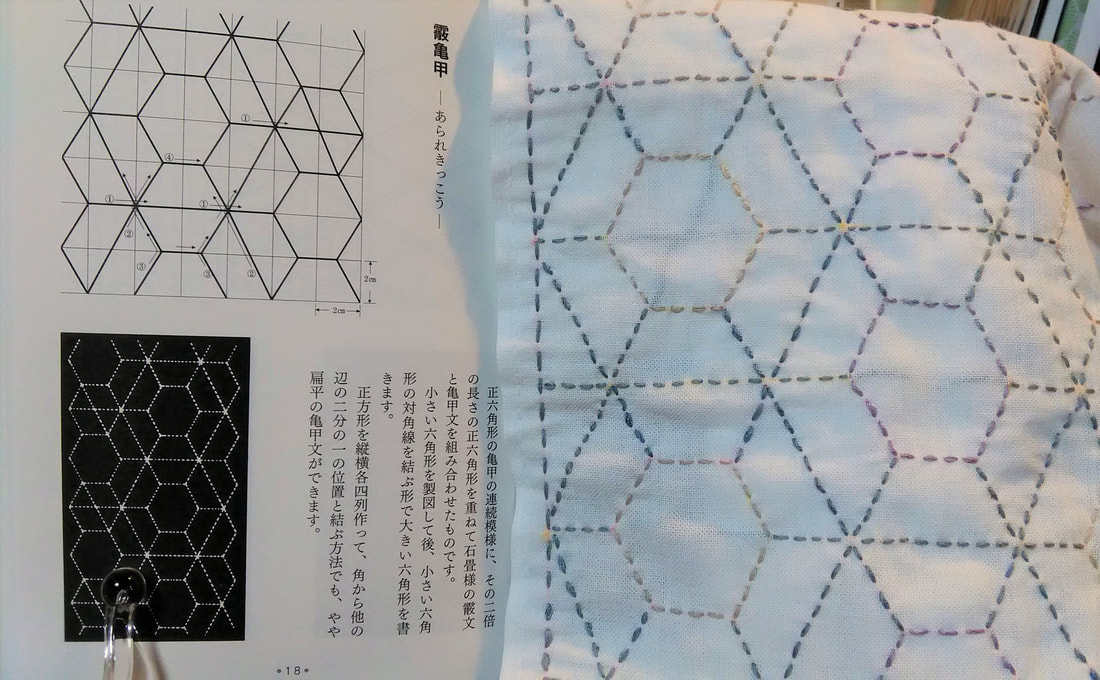

Can you see the connection between this piece of sashiko and soccer? Read on and discover more. Sometimes I think that sashiko has rewired my brain, because I can’t help noticing patterns in everyday objects all around me, and seeing them in terms of sashiko. During the world cup soccer it was not only the Samurai Blue uniforms that caught my eye, but the soccer balls too. Did you know that a soccer ball is made up of 20 white hexagons and 12 black pentagons? When I see hexagons I think of kikko (tortoiseshell) and its many variations. The hexagon is called this in Japanese because of its resemblance to the shell of a tortoise, which since ancient times has signified longevity and the wish for immortality, hence it use as an auspicious symbol and use in sending wishes for long life and congratulations. Recently I’ve been doing some research on the origins of hanafukin from a book called “Folk Clothing Culture: Sashiko Research” (by Kiku Tokunaga). It was published in 1989 and is out of print, so I was thrilled to discover it through an online second-hand bookshop, and now think of it as my sashiko bible. From this book I discovered that the earliest known use of the word hanafukin was for the cloths made by the wives of pioneer settler samurai from the Uesugi clan, which moved to Yonezawa, in Yamagata northern Japan in the seventeenth century. These cloths were placed near wells or rivers where people washed their clogs, and also in the entrance to houses for guests to wipe their feet on. The hanafukin placed in the front entrance of each house functioned as the “face” of that house to visitors and were stitched with a variety of patterns that were also supposed to represent clan beliefs, and serve as a reminder to the farmer soldiers coming back from their work in the fields of their samurai status. Hanafukin were larger than ordinary cleaning cloths, and required a lot more stitching. One technique was to divide the area into split sections that were then filled various patterns, but the shape most frequently used to divide up the sections was – you guessed it…hexagons! There’s a whole lot more to be said about the significance of the different patterns stitched inside these hexagons, but I’ll leave that for another time. For the moment let’s just say that I am only beginning to scratch the surface of the amazing history behind the humble hanafukin. Recently I was moved to stitch a tortoiseshell hanafukin myself, with the arare kikko ‘hailstone tortoiseshell’ pattern. In this variation there are two hexagon patterns, one twice the size of the other, which overlap to produce a ‘hailstone’ effect. The photograph at the top of this page is a small cloth I stitched with tsuno kikko, which means ‘horned tortoiseshell,’ but I do think that’s a misleading name, because to me these look more like flowers than horns! Here’s another cloth I stitched which I have on display in my front entrance hall. This is mukai kikko, the alternate or facing tortoiseshell. When flicking through my collection of sashiko books I also found these lovely coasters with kikko, juji kikko (cross tortoiseshell) and tsuno kikko. Perhaps the coasters of today are what hanafukin once used to be to farmer samurai households. This is from the book Hajimete no sashiko: shimpuru na harimega utsukushii fukuromono to komono (Sashiko for beginners: Bags and small items with beautiful simple stitching), (Nihon Vogue, 2012 - Amazon affiliate link)

Once you become aware of kikko, you’ll get like me and start seeing it in everything from paving stones to soccer balls! Dear sashikoists and regular readers of this blog. Apologies for my sudden disappearance, but recently I found myself having to put in long, intense hours at the computer in my regular day job as a literary translator, and couldn’t bear to look at it much otherwise. But of course I kept stitching, and once again sashiko helped me get through a difficult period. I’ll tell you more about the projects I’ve been working on in posts to come, but for now I simply want to talk about what jolted me out of my slump – which was soccer. An unlikely topic for this blog, especially as soccer doesn’t actually interest me very much, but there is one compelling reason I’m not averse to watching the Japanese soccer team in action at the World Cup in Russia, and that is their uniforms! Every time I glimpse the broken parallel lines of the sashiko design on the players' shirts, my heart skips a beat. Regular readers may recall that I mentioned the announcement of this design for the team's new uniform in a post last November. Deep indigo blue has a long tradition and history in Japan, but the reason for its use in the design concept of these shirts, is because 15th and 16th century samurai commanders used to wear kimono of this shade under their armour, hence the idea of its use as a 'winning colour' for the base colour design of the uniform. Add to this the sashiko pattern, which represents connecting up the threads of history to mark the twentieth anniversary since Japan first debuted in the French World Cup in 1998, and you have a winning combination. The strategy certainly worked, because on Wednesday June 20, the Japanese team made history by winning their first match in the tournament, beating the favourite in their group, Colombia, by 2 to 1. It was also the first time an Asian team had defeated a South American team in the men’s World Cup. In this case a win for the Japanese soccer is also a win for Watts Sashiko, because it has inspired me to get writing again.

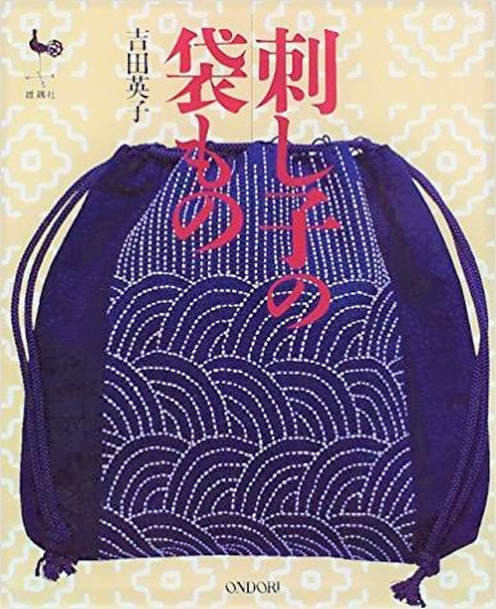

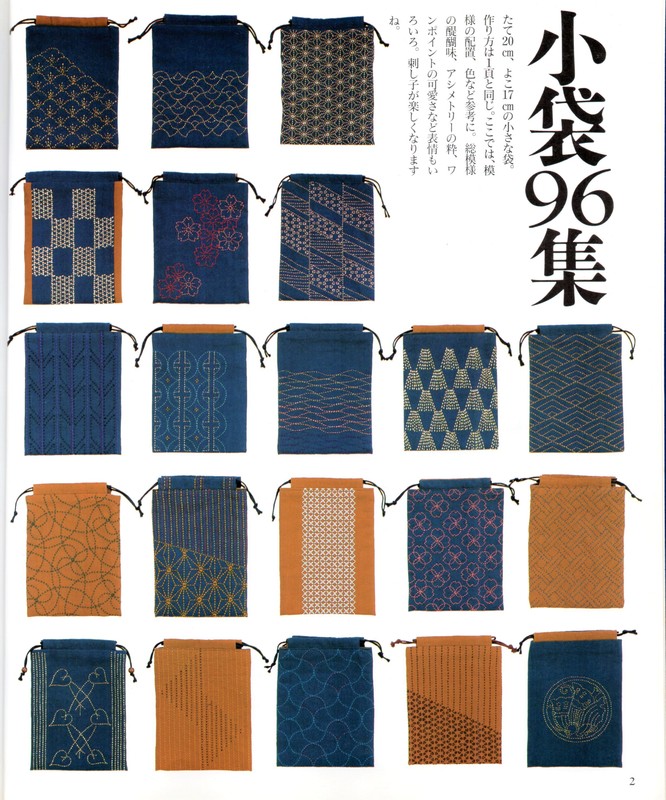

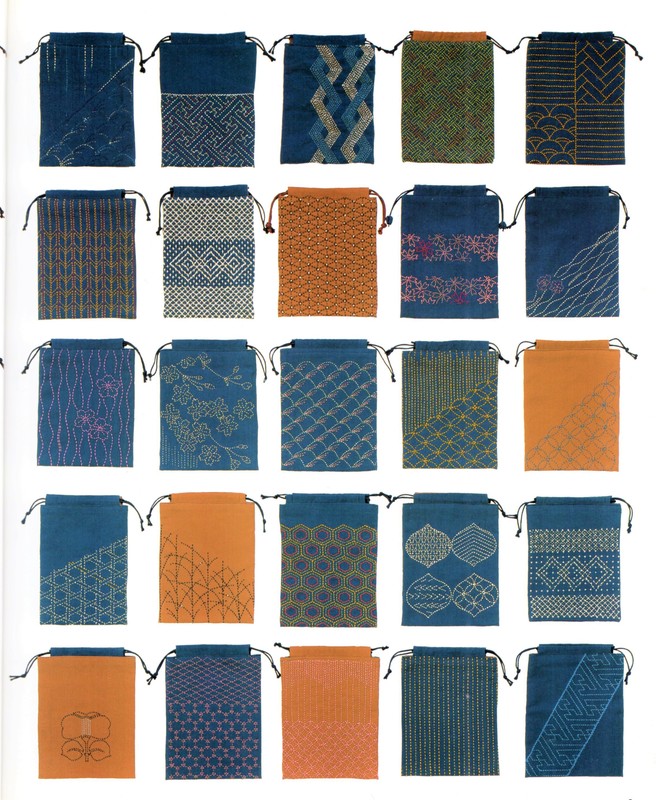

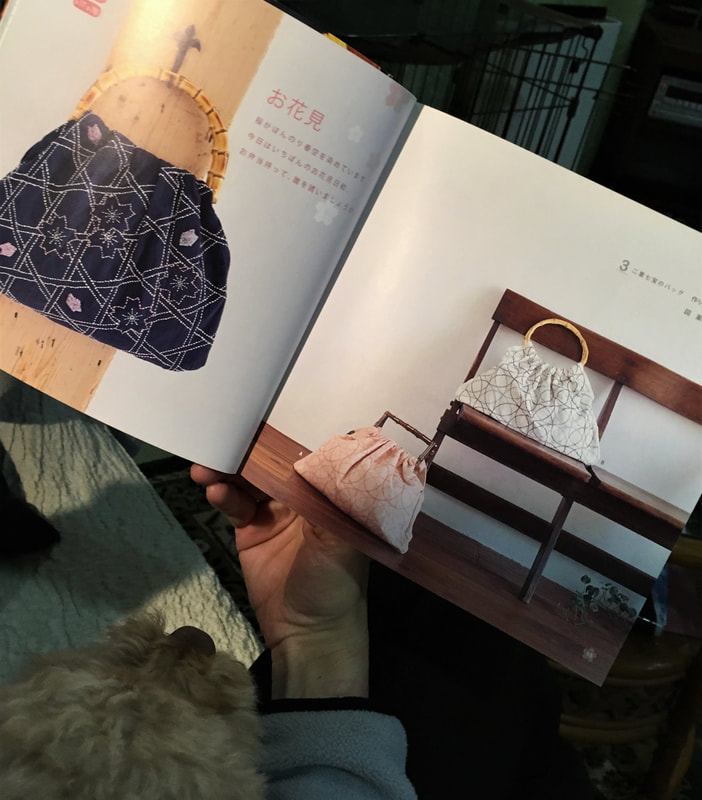

So I’ll keep this short and sweet for now, but I promise to be back again soon! After writing in my last post about the exquisite kinchaku bag I received, I felt like revisiting a book in my collection featuring kinchaku and other bags. This book, called Sashiko no fukuro mono (Sashiko Bags - Amazon Japan affiliate link)), was published by Ondori in 1998 and written by Eiko Yoshida, who you may remember I mentioned before as being my teacher’s teacher. Eiko Yoshida (1922-2002) was born in Honjo, Akita prefecture, and helped created a boom in the revival of sashiko’s popularity in the late twentieth century. Akita sashiko is noted for the use of colorful thin silk thread and single cotton thread, and Eiko herself was apparently born into a family with a Japanese-style clothing business, so perhaps these factors combined account for the sense of style and design she is known for. Ei Rokusuke, a well-known writer, radio and TV personality used to wear a sashiko hanten (padded jacket) stitched by Eiko for stage appearances. You can certainly see an artistic and discerning aesthetic behind the designs featured in this book. She writes in the introduction (p.1): “I created sashiko bags with traditional Japanese patterns and a fresh sensibility. Items made according to the age-old practice of stitching indigo cotton with white thread have a soothing elegance. But these same traditional patterns can give rise to new expression through fabric, thread and design. The beautiful 20cm by 17cm drawstring bag pictured below is ample illustration of that. The next four pages then show 96 design variations for this same bag! The variation in sashiko patterns, colours and arrangements of designs is simply amazing. What a cornucopia to take inspiration from. I admit I haven’t made this bag, but the instructions given on page 36 don’t look too difficult. I make no guarantee, but a skilled seamstress would possibly be able to work out what to do from the diagrams even if you can’t read the Japanese. It requires a piece of cloth 52cm by 19cm, lining 42cm by 19cm, 100cm cord, and thread for the sashiko. If anybody does attempt it, please let me know. Only the design template for the bag pictured on page 1 is given, all the rest you would have to find for yourself, or even better, create your own! There are many other types of bags in this book – shoulder bags, handbags, glasses cases and various types of kinchaku – with to-die for designs and instructions for making (all in Japanese), and after flicking through it yet again, I can feel a bag fetish coming on.

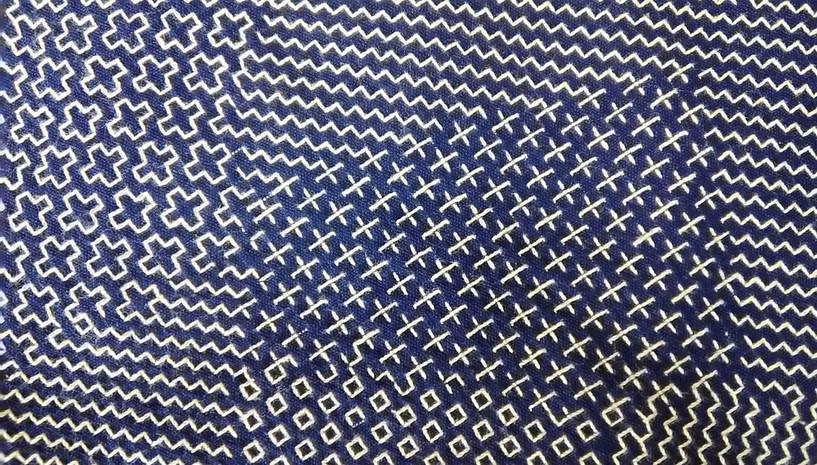

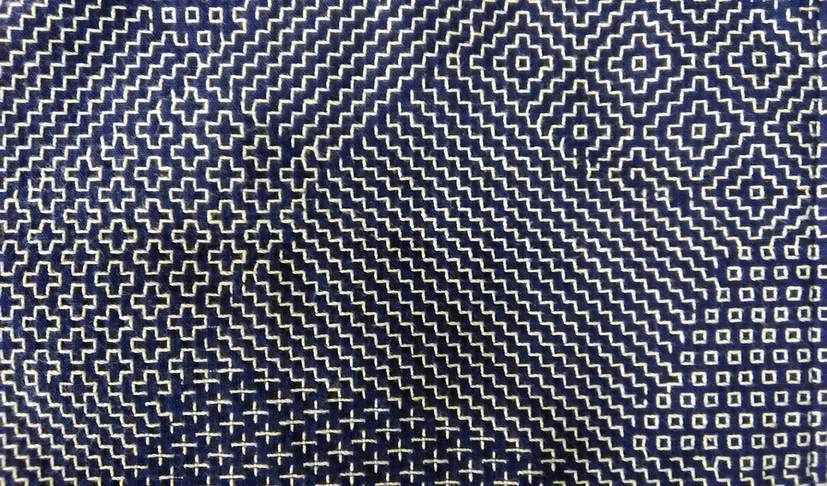

Imagine my delight when the postman delivered me a package recently, and I opened it up to find this gorgeous drawstring bag inside, a gift from an acquaintance who thought I could appreciate it. And she was right! I oohed and aahed with admiration as I examined it every from angle, resisting the temptation to unpick the beautiful red lining and peek at the underside. This type of bag, called a kinchaku in Japanese, was—and still is--used to carry around valuables or personal effects. Although an accessory for Japanese-style clothing, and probably not as common as it once used to be now that Western dress is the norm, it is nevertheless, far from having fallen out of use. I often see the elderly ladies in my neighborhood out for a daily walk clutching their kinchaku. And schoolchildren keep stationery, or implements for school lunches in these bags, though they are far more likely to be decorated with cute characters than sashiko. At summer festivals kinchaku are a common accessory for traditional festival wear, in fact I have a fancy red one to go with my yukata (cotton summer kimono). Naturally cloth kinchaku are ideal for sashiko, and the choice of pattern can indicate anything from seasonal themes to protection from evil spirits or wishes for a long life, or simply a something that catches the maker’s fancy! I’m not sure what dictated the maker’s choice of patterns for my new kinchaku, but it is stitched with a selection of five hitomezashi patterns, typical of the Shonai region in Yamagata prefecture. These are: two types of jujizashi (cross stitch), yamagata (mountain form), sanju kakinohanazashi (triple persimmon flower stitch) and kuchizashi (mouth stitch). I love the way the blocks merge without any border between them. And I am awed by the quality of stitching, which is just incredible! Every stitch is so perfectly aligned and neat you would almost think it was done by machine, but of course that is impossible. Owning this bag will certainly be an inspiration to me to up my game. I am almost embarrassed to post the picture of the one and only kinchaku that I’ve ever made. I find it very useful for holding all the thread, needles and tools together for whatever sashiko project I have on the go, but it’s such a handy item I often divert it for other purposes as well, so making more is on my list of items to do. In the meantime I have my lovely new kinchaku, but I don’t want to spoil it with knockabout use so I’m still deciding what to use it for. One thing I know; I will walk a little straighter when I carry this beautiful bag on me.

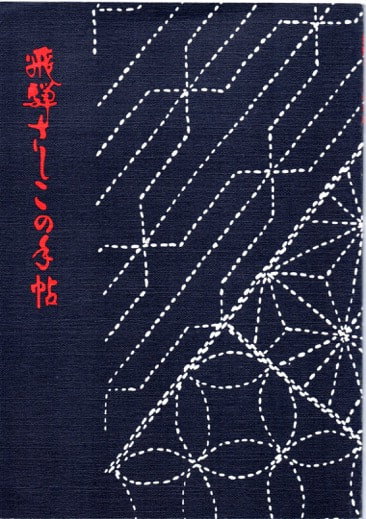

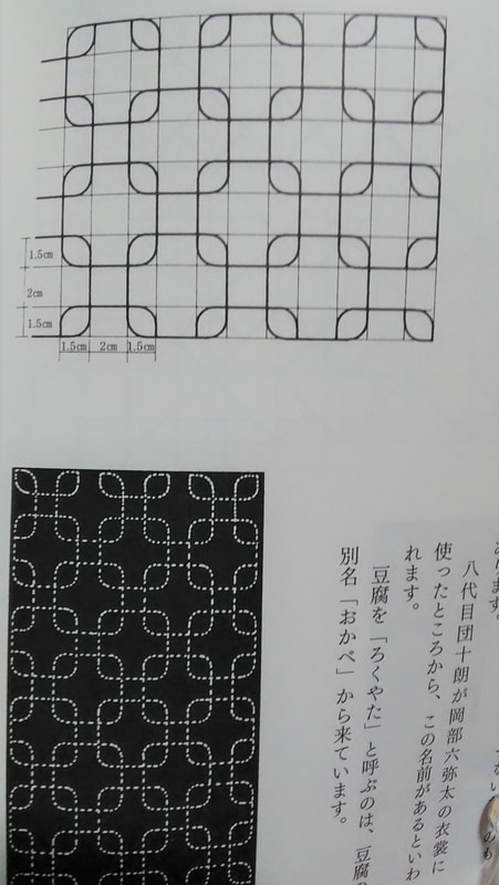

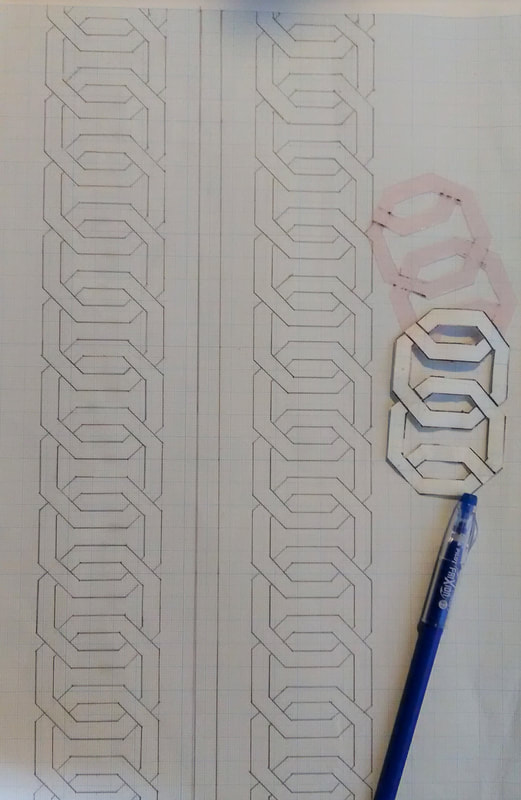

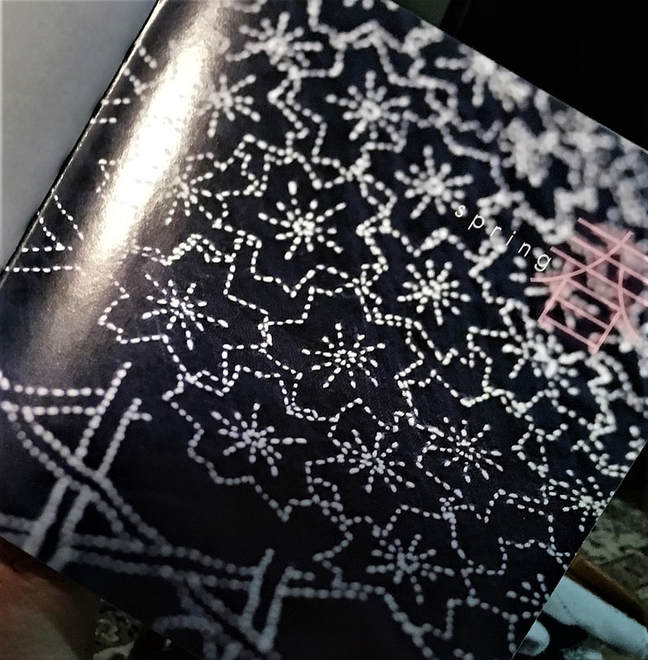

When I visited the Hida Sashiko exhibition last year I purchased a small book called Hida Sashiko no Techo (The Hida Sashiko Notebook, by Reiko Futatuya, first released in 1978, reprinted 2013, published by Hida Sashiko), as I always do whenever I come across a book about sashiko that’s not in my collection. Every book has its own appeal, and I never tire of looking through my collection and taking in the variety of sashiko styles and applications. Anyway, by today’s standards this book is very simple; thirty three pages in mostly black and white, and basically just a reference for patterns, but in 1978 when it was first published I doubt there were many books about sashiko available, so I am sure it would have been a valuable resource. (Still is, actually. I found it referred to less than a year ago on this blog, which is written in Japanese, but the photographs are lovely.) As with most such books there is a general description of sashiko’s roots in reusing and reinforcing cloth, but I liked the concrete examples given; for example stitching the tabi (socks) worn by the boatmen transporting lumber down the river to make the sole non-slip in the water; or stitching a chrysanthemum motif in the in the corner of a furoshiki (wrapping cloth) to prevent knots coming undone. There’s a brief discussion of cloth (hemp, cotton and silk), thread and needles, and tools with the general advice of choosing the thread and needles to suit your purpose. All in all there are twenty-eight designs introduced, which the author says are a sample of those most commonly used in Hida, and are a mixture of hitomezashi (one stitch), and moyozashi (pattern sashiko). Each design has a simple explanation of the name, composition and roots, and shows the dimensions on graph paper so that the patterns can be reproduced and adapted. Most of the patterns were familiar, as I had seen them before in various forms in other sashiko books, but I did find a couple that were completely new to me. One was Roku Yata goshi (Roku Yata lattice), so-called because it was used on the costume of a popular kabuki actor in the early 19th century when he played the role of a samurai called Roku Yata, and the pattern became hugely fashionable. Another was Yoshiwara tsunagi, (linked Yoshiwara) a series of linked octagons, which I have seen printed on towels and clothing but never as sashiko. According to this book it is often used for actors and dancers stage costumes. Further research led me to discover that it was used on the curtains of teahouses in the red-light Yoshiwara district in Edo, hence the name Yoshiwara. For some reason this design struck a chord in me; I love the suggestion of strength and complexity, in a compact simple line – and felt compelled to make something with it, so I stitched it onto the back of my jeans jacket. When Reiko Futatuya wrote that she hoped these patterns would be used for new fabrics and purposes, I don’t expect she imagined this! When winter snows are deep and customers are few, then is the time for artisans to close up shop and take their wares on the road. Of course this may not be as necessary nowadays with online shopping, but one such travelling exhibition that regularly comes to the Yokose Gallery near me in winter, is Hida Sashiko from Takayama in Gifu prefecture. Gifu prefecture is in central Japan, far from the northern Tohoku region where the so-called three main types of sashiko (Shonai, Tsugaru Kogin and Nanbu Hishizashi) are said to have originated. Whether sashiko started in one particular region and spread from there, or developed independently all over the country is not clear, but it is true that sashiko is found all over Japan, from Okinawa to Hokkaido. Hida is both the name of a city and a region in Gifu, where sashiko is commonplace, so Hida sashiko could refer to sashiko of the region, but this exhibition was from the Hida Sashiko company based in Takayama city, Gifu. The family-owned company was originally established in 1975, however various disputes led to two members of the family setting up their own companies. Keiko Futatsuya established Sashi.Co which focuses on designing, clothing and sashiko supplies, while her son Atsushi Futatsuya runs Upcycle Stitches which offers sashiko supplies and workshops, and is generally spreading the word about sashiko in English. It’s fascinating to see the way this dynamic pair are adding new dimensions to the sashiko world, especially as the appeal of sashiko grows internationally. Anyway, perhaps it was because of the cold wintry weather when I went to see the Hida Exhibition, that I only had eyes for flowers and cherry blossoms. To be sure there were many bags, cloths, and coats with exquisitely stitched hitomezashi (one stitch sashiko) and moyozashi (pattern sashiko) designs, but seeing the cherry blossoms incorporated into wall hangings made me feel as joyful as any flower-viewing party, and after feasting my eyes I went home smiling.

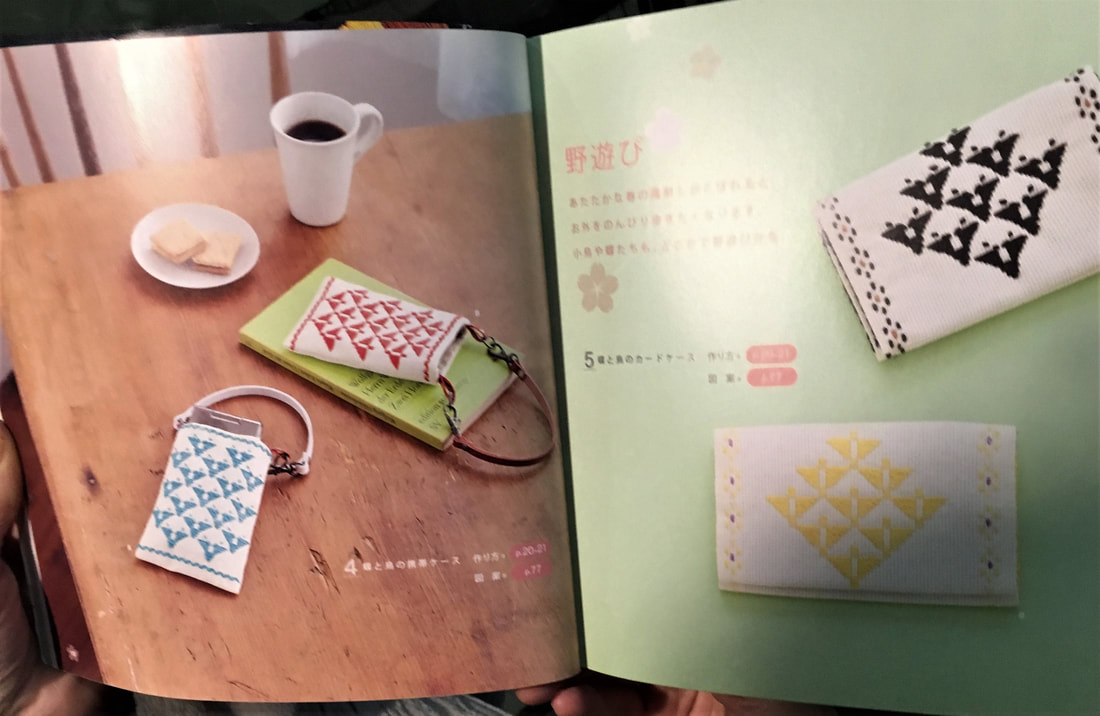

With thoughts of spring at the end of a long winter, I picked out Sashiko no Zakka (Sashiko Everyday Items, by Hideko Onazaki, (Tatsumi Publishing 2010 - Amazon Japan affiliate link) from my collection, looking for inspiration to decorate my daughter’s new denim skirt. The reason this particular book sprang to mind was because I knew it was arranged around seasonal themes. Each one of the four chapters is devoted to a different season, and features a wide variety of practical everyday items to make, in particularly cheerful, fun and colourful designs. Opening to the spring page, I saw an adorable combination design of cherry blossom and basket weave in white stitching on blue fabric that set my heart singing. The mini work jackets featuring this design on the next page are almost too cute to be true, and I almost wished I still had babies I could make one for. The jackets stitched in orange and yellow hemp leaf, red cherry blossom and basket weave, blue linked weights, and white net-enclosed flower designs, were all equally sweet. Other items in the spring section were bags, card cases and phone cases, featuring flower and butterfly patterns. The summer chapter has a tablecloth, hanging curtain, cushion covers and more bags. (In fact the variety of bags in this book is a feature. I counted four different types.) In addition to the traditional Bishamon sashiko patterns, the items in this chapter feature freestyle patterns in fitting with the summer theme, of fish, waves, umbrellas and sea creatures. The autumn chapter has patterns for bags, pouches, pen and card cases in more subdued autumn tones. A densely stitched circle of hitomezashi hemp leaf pattern combined with a free style rabbit that decorates a handy all-purpose pouch particularly caught my eye. It’s a lovely image of a rabbit staring at a large autumn moon, and something I’d like to make in future. Ironically, I found the inspiration for my daughter’s skirt in the winter chapter, on a stole stitched with roses. Fun sashiko Christmas cards and a snowflake patterned stole are also in this chapter. I like the fact that the instructions for making each item are on the following page, so one is not forever flipping between the back and front of the book to find the right page. The sashiko pattern templates, however, are all together at the back. Not to scale, obviously, as that would not be practical in a book this size, but there are also no grids or dimensions given that would make them easy to reproduce on graph paper. I enlarged the rose design on a photocopier and used transfer paper to print it on the skirt. In the course of stitching the design rubbed off so I kept retracing with my Karisma Fabric pen.

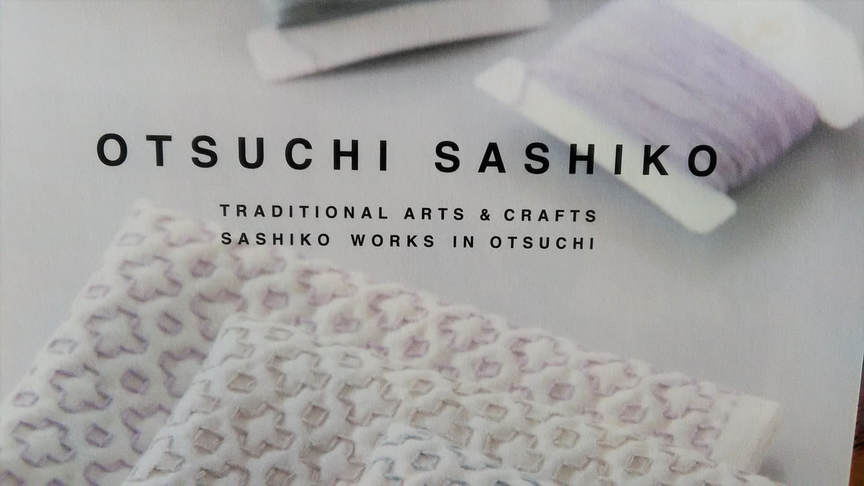

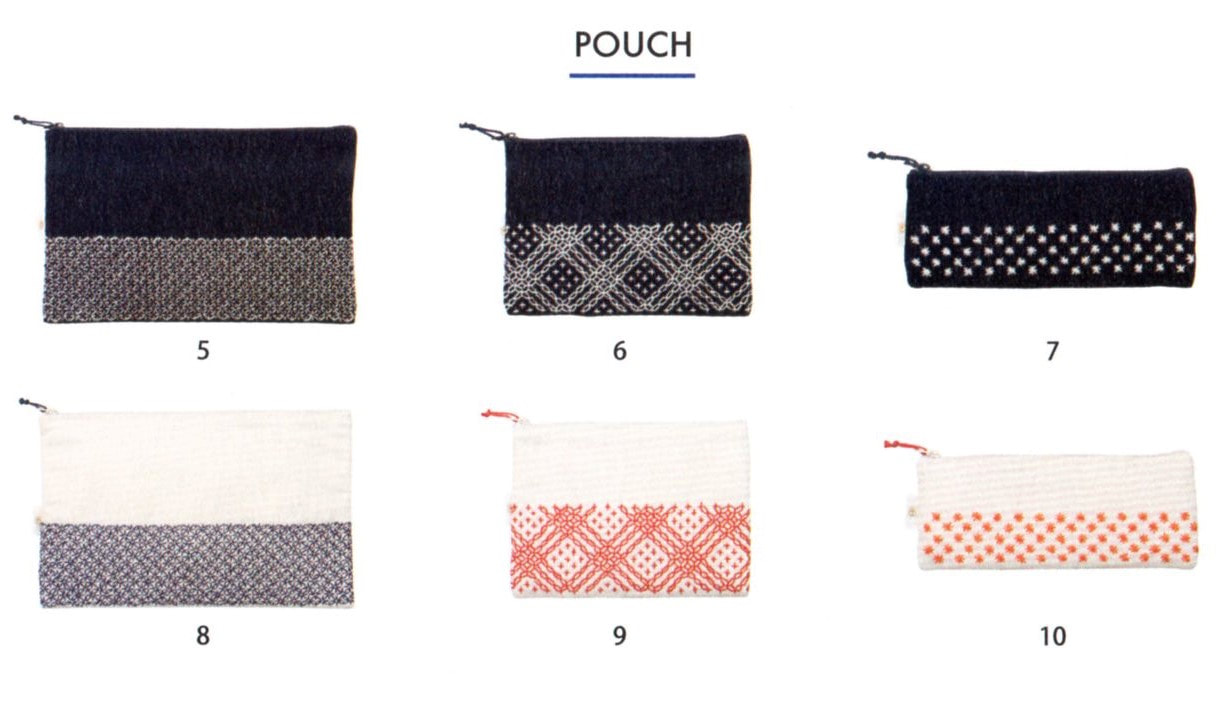

As with most sashiko books there are pages devoted to very basic instruction on transferring patterns and stitching. You would also need prior sewing knowledge and experience to actually make the items. It’s not a book for beginners to learn sashiko from, but if like me you are simply looking for some quick inspiration, it’s a wonderful resource! If you want to know more about the power of sashiko, here’s a story for you. It’s about a place called Otsuchi, and sashiko changing the lives of people who had literally lost everything. Otsuchi (pop. approx. 12,000) is a town on the coast of Iwate prefecture, which was devastated by the tsunami in 2011. One young volunteer from Tokyo who went there, Kazuya Yoshino, saw people living in evacuation centres, having lost their livelihoods, and realized that there was a need for new forms of income, but it had to be something people could do in the crowded confines of evacuation centres. He came up with the idea of sashiko and with four other volunteers, founded a group to make sashiko as an income-earning venture. The Otsuchi Recovery Sashiko Project was born on May 4, 2011, and on June 5 the first sashiko meeting was held at the Otsuchi Central Community Hall. The volunteers scouted materials for the sashiko stitchers, arranged teaching sessions, and found outlets to sell the finished items. More and more people of all ages joined the project, from teenagers to octogenarians, and even some men too. By August 2011 the number of members had grown to 60 and the group had reached its limits as a voluntary organization, at which point an NPO called Terra Renaissance officially took over its management. Terra Renaissance aims to transform it into a self-sustaining business within ten years, by developing a line-up of products, honing skills, and increasing sales outlets. Mother and son, Keiko and Atsushi Futatsuya, are also key figures in supporting the Otsuchi Sashiko project, assisting with the supply of materials, expertise and guidance. The two are from a sashiko family business in Takayama, Gifu prefecture (central Japan), which is home to another type of regional sashiko known as Hida sashiko. Atsushi is the third generation in a sashiko family and knows only too well how difficult it is to run a sustainable sashiko business. He heard about the Otsuchi project and first made contact in June 2011, went there in November to see for himself, then returned in February 2012 for two months to assist with training and management. Atsushi and Keiko also conceived the Otsuchi Sashiko Hundred Bag Project to help develop product quality, skill and business sustainability.

I’m sure there must be many other people whose efforts and contributions have kept this project going. What I’m telling you here is only a small part that I’ve gleaned from blogs and websites. The project went from strength to strength and currently has approximately thirty stitchers, ranging in age from 20 to 80. One example of its success in developing consistent high quality products is its relationship with Muji, the renowned quality home goods retailer. Muji has been selling selected products from the project since 2013. I’m sure that we will hear more about the successes of Otsuchi Sashiko as time goes by. I also have a feeling that we are witnessing history in the making, the birth of a new regional sashiko: Otsuchi Sashiko. Otsuchi Recovery Sashiko Project online store. Though the site is in Japanese, you can still see the lineup of beautiful items. Follow the project here on Instagram . |

Watts SashikoI love sashiko. I love its simplicity and complexity, I love looking at it, doing it, reading about it, and talking about it. Archives

September 2022

Categories

All

Sign up for the newsletter:

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed